#YoSoy132, a year later

December 2nd, 2013 by andresmhLast year, Gilad Lotan and I spent some time analyzing the #YoSoy132 protests in Mexico using data from Twitter. Several articles and even books about #YoSoy132 have come out since. For example, De Mauleón wrote an excellent piece for Nexos (in Spanish) that resembled some of our own analysis. Sadly, Gilad and I got busy and abandoned the project, but after this recent conversation, we decided to dig out our notes and post them here in the event that they might be useful for others.

The rise and fall of the “Mexican Spring”

Exactly a year ago, in December 2012, the newly elected Mexican President Peña Nieto took office amid violent protests. As early as May 2012, a number of massive student protests against the then candidate Peña gained a lot of attention on social media, both inside and outside Mexico. The Occupy movement and the international press called these protests the Mexican Spring for its similarities with other “hashtagged” protests. In our analysis, we only focused on the first few months of the protests. Today, #YoSoy132 is only a shadow of what it was, but during the election it was able to accomplish several important victories, including the organization of an online presidential debate (broadcast on YouTube), and the introduction of the issue of media monopolies and media bias to the forefront of the political discussion.

We focused on the origin and spread of the #YoSoy132 student protests by lookign at Twitter trending topics, follower connections, and the content of the tweets. We found that despite the common assumption that the movement appeared “out of the blue,” after an incident involving a candidate’s visit to a university, we can actually trace the movement’s gestation to several months before the trigger incident. Additionally, we found that despite the attempts to link the movement to traditional political groups, i.e. a political party, the movement actually activated typically disconnected groups of people across the political and class spectrum.

The birth of #YoSoy132

The incident that marked the movement’s birth was the May 11 visit of leading presidential candidate Enrique Peña Nieto (EPN) to Univesidad Iberoamericana (known as “Ibero”), an elite private university in Mexico City. The university was not traditionally associated with political protests, however, that day, hundreds of student protesters forced Peña to literally run away from the campus. As Peña was leaving the university, he told reporters that the protesters were “not genuine.” Likewise, members of his party spun the story, claiming that the protesters were “intolerant,” too old to be students, and possibly planted by Peña’s political opponents. Several news outlets played down the incident, and some even reported it in ways that differed the students’ recollections of events. Most notably, students were angered over a newspaper headline that referred to Peña’s visit to Ibero as a “triumph,” and implying that the protesters were part of an “orchestrated boycott attempt.”

Angered by the accusations and what the perceived was yet another example of the unfair media coverage, students replied with a YouTube video titled “131 students of Ibero respond.” The video showed short clips of 131 students stating their name while holding their student ID card. After the video exploded in popularity on social media, the movement grew and spread to several cities in Mexico and throughout the Mexican diaspora around the world. The protests were called #YoSoy132, Spanish for “I am 132,” in honor of those 131 students in the YouTube video.

Visibility through Twitter trending topics

By the time the protests started, Twitter had been quite visible throughout the campaigns. For example, the media and the candidates have been using Twitter follower counts as a measure of their popularity. This only helped incentivize the candidates’ desire to manipulate Twitter’s trending topics and other online presence markets. For example, Peña was accused of acquiring armies of twitterers to manipulate Twitter trending topics, as evidenced by a leaked video showing members of Peña’s campaign using this tactic during one of the debates.

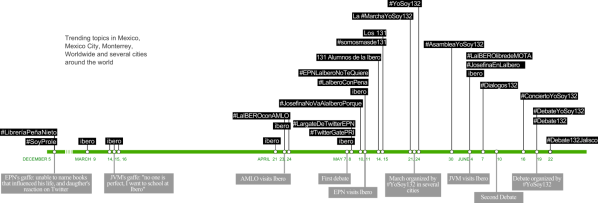

Twitter trends give insight into popular topics in locations across the world. When a new hashtag, word or phrase is used enough times in Tweets originating in a certain geographic region, it is highlighted in the trending topics list. We use Twitter trending topics across geographic locations to put together a timeline of the major events, understand when events hit a certain tipping point.

During Peña’s visit to Ibero University on May 11 the term ‘ibero’ trended across cities of Mexico, the United States and Canada. Although the term ibero had not been mentioned as often before the May 11 spike, we found that the discontent against Peña’s campaign on social media predates this event. In the list of trending topics, we can see how Peña’s conflicts with the Mexican twittersphere date back to December 2011 when he had an embarrassing slip as he was unable to list the books that had influenced him the most during his own book presentation. To make matters worse, after the incident exploded on Twitter with the hashtag #LibreriaPenaNieto (Peña Nieto’s bookstore in English), his daughter retweeted a message calling her father’s critics “a bunch of proletariat a**holes,” leading to the meme #SoyProle (I am proletariat).

More specifically with regards to the term ibero, we noticed that it had trended a couple of times before May 11 suggesting that Ibero students were already sufficiently engaged on Twitter. Also, the dates on which ibero trends match events related to the elections. For example, the term trended from March 14 to 16, matching both the visit the leftist candidates to the Puebla campus of the university and a gaffe by Vazquez Mota, the conservative candidate, who implied that being an Ibero alum herself made her “imperfect.” Furthermore, we see ibero trend on Apr 21, the day after EPN rescheduled his visit to the university, and again on April 23 when López Obrador, the candidate from the left, visited the university. We see ibero trend again on May 8 after EPN cancelled his visit to the university a second time. The timing and frequency of ibero in the trending topics suggests a high level of political engagement by Ibero affiliates on Twitter before the May 11 incident.

Activating Typically Disconnected Groups

One of the most striking things about the #Yosoy132 protests was how its message activated groups that are traditionally disconnected, both across socioeconomic class and political affiliation. The movement was started by students at Ibero, one of the most exclusive universities in Mexico, but quickly gained traction among students from public universities, often positioned in ideological antagonism with private schools. We can see this in the network graph of entity co-occurrence that highlights the relationships between words. Whenever a word is used along with another word in a Tweet, they are said to “co-occur”, hence the edge that connects between the two nodes that represents the words becomes stronger. We see the names of other private universities (e.g., #itam, #tec, #itesm, #lasalle, #uvm) as well as public ones (e.g., #unam, #poli, #uam, #uaem, #uanl) appear in messages related to the #YoSoy132 protests.

Furthermore, while the movement seems to activate more leftist groups, it also activated right-wing ones. For example, we observe a cluster from the right-leaning twitterers at the top-right corner of the plot, and left-wing ones on the mid left and right areas.

Reflections

The #YoSoy132 movement was a movement of the middle class youth, markedly outward-looking. It was not surprising then that the aesthetics of the #YoSoy132 movement, at least at first, resembled the international hashtagged movements, such as Occupy, Indignados, and the Arab Spring, more so than local movements like the Zapatistas. Unlike the Arab Spring, it seemed that #YoSoy132 was much more about a struggle against old media, TV in particular. The Arab Spring might have used social media to gain international recognition and to help people organize themselves at first, but it continued even when social media was censored. In contrast, #YoSoy132 existed primarily through social media. Social media were as much the medium as they were the message.

The movement rallied young people against the alleged manipulation by large media networks, in an apparent effort to determine the next president. Despite the movement’s antagonism with mainstream media, it was able to gain visibility and respect from a wide-range of political actors. The movement’s visibility was propelled by public-facing social media platforms such as YouTube and Twitter, while also relying on pre-existing offline networks that organized themselves using a combination of face-to-face interactions and private Facebook groups. The challenges and benefits of decentralization that included a disparate set of social media outlets, some of which were taken over by opponents of the movement and later recovered by the hacker collective Anonymous. The official results of the election, suggest that despite the strong social media presence of the #YoSoy132 movement, the election results highlight the limitations of social media in reaching beyond those who were already networked.