Boston Route 128’s Past and Present (2)

Boston Route 128’s Past and Present, Vicissitudes of Political Life

“Better the occasional faults of a government that lives in a spirit of charity than the consistent omissions of a government frozen in the ice of its own indifference.” —— Franklin D. Roosevelt

Officialdom can hardly be a long-time lover. —— The Scholars

If a person were interested in the American public’s opinions about their country’s economic performance, he or she would easily notice their contradictory attitudes toward the role of their government. When the economy is booming, people oftentimes attribute the growth to factors extraneous to the executive power such as entrepreneurship, technological progress or international environment. In times of economic stagnation or recession, they would hold the government accountable for its demotivational or ill-considered measures. All kinds of criticism, accusation and even denouncement would come flooding in from every walk of life. Indeed, it takes not only integrity and sacrifice, but in particular “good temper” and “magnanimity” to hold key political posts in America.

The American people’s “vigilant” and “prudent” attitudes toward the government are reinforced in the mutual fault- picking and derogatory attacks between the Democratic and Republican parties. In fact, the two parties’ divergence with regard to the function and role of the executive branches of the government remain as the touchstone of their fundamental difference. However, their respective positions on the economic policies are not as clear-cut as “interference” versus “laissez-faire”, nor can the specific measures they take simply be labeled as “conservative” or “liberal”, “left” or “right”. In his 2012 State of Union Address, President Obama made the following statement, with which many well-intentioned politicians may side, “I believe what Republican Abraham Lincoln believed: ‘That government should do for people only what they cannot do better by themselves, and no more.’”

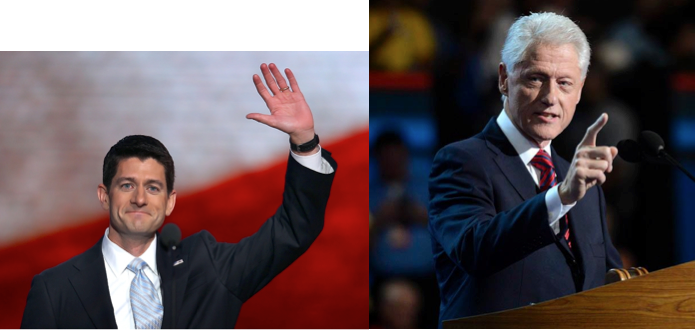

Ryan and Clinton, whom will the people trust?

http://articles.nydailynews.com/2012-09-06/news/33623274_1_democratic-party-jobs-equal-opportunity)

The recently concluded Republican and Democratic National Conventions, while making formal declarations of their respective presidential nominees, also staged a vigorous debate on the assessment of current economic situations and of the present economic policies. Republican vice presidential candidate, Paul Ryan, attributed America’s high unemployment rate and deterioration of credit rating directly to Obama’s incompetence. In his eyes, the president’s promise of “change” four years ago has delivered nothing but “fear and division”. Obama failed to prioritize job creation on his agenda; instead, he got Americans into “a long, divisive, all-or-nothing attempt to put the federal government in charge of health care”, which not only intensified bi-partisan conflicts but came at the expense of the elderly. Obama’ s best shot at fixing the economy was a costly stimulus plan; however, the $831 billion went to companies like Solyndra, which announced bankruptcy in September 2011, not long after its acceptance of the funding. Indeed Paul saved little face for Obama by so bluntly saying that the president had wasted the feelings, time and money of the American people! In contrast, former president Bill Clinton’s remarks at the Democratic National Convention, at least on the surface, was much more courteous. Yet his rebuttal to all the major criticisms from the Republicans was equally vehement. By reviewing the presidency history of the two parties since 1961, Clinton pointed out with pride that with shorter ruling period, the Democratic presidents had produced more jobs than their Republican counterparts. With specific data, Clinton defended Obama against Ryan’s accusation of hurting the elderly. On the contrary, Clinton held that Obama’s reform would “add eight years to the life of the Medicare Trust Fund”, extending it from 2016 to 2024. Obama’s policies to support education are, moreover, of strategic importance and far-reaching significance. Drawing on his own experience as president, Clinton encouraged his fellow Americans to give the president a bit more time, because, to quote him, “No President – not me or any of my predecessors could have repaired all the damage in just four years.” Both Ryan and Clinton sounded uncompromising and reassuring, but whom can the people trust and whom will they trust?

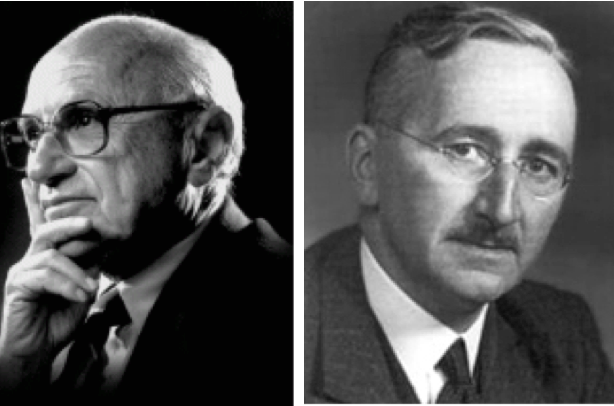

Academia certainly would not remain silent, and a warning voice came from Stanford University on the west coast, “American economy faces an uncertain future…the reason for this predicament is clear: we have deviated from the principles of economic freedom upon which America was founded.” If John B. Taylor was echoing his concerns with Hayek’s works and ideas in his article “The Road to Recovery”, he was also emphasizing that as rightly perceived by Hayek, freedom and rule of law are the key to prosperity, policy-makers must adhere to rule of law and predictable policies, for only stable policies can sustain economic growth. ” On July 31, 2012, the centennial celebration of Milton Friedman, also held at the Hoover Institution Stanford University, could be seen as a straightforward critique on “big government”, “governmental regulation” and “aggressive fiscal policies.” Indeed, the criticisms made decades ago are still astonishingly relevant today!

After being hit by the most severe economic crisis since the Great Depression in 1930s, Americans today pay unprecedentedly close attention to their domestic economic situation. People have every reason to expect that the “economic card” would be the watching focus of this year’s presidential campaign and that economic issues would ultimately determine who becomes the next host of the White House. Against such a complicated backdrop, will there emerge a set of economic policies marked by wisdom, practicality, innovativeness and minimum controversy out of the presidential campaign? Perhaps such a wish is hard to gratify.

Two worldly renowned and respected economists and advocates of “free market”, Milton Friedman and Hayek Friedrich A. von

With earnest attention and expectation, let us look back on the history of Route 128, and following its rise, decline, resurgence and steady development, recollect the performances of several former governors of Massachusetts from both parties. Through the ups and downs of their political lives, we may be able to gain some valuable insights.

* * *

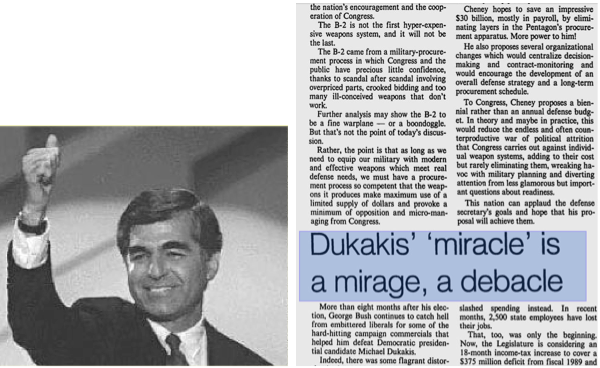

Michael Dukakis was the man who single-handedly created the “Massachusetts Miracle” and later eye-witnessed its collapse. But Route 128, which was built during his term, has taken its fame thenceforth. Dukakis’s political life had quite a legendary flavor—he lost one election, won a reelection, and fulfilled three terms (1975-1979、1983-1991), serving the longest as governor in the history of Massachusetts. The “Massachusetts Miracle” enabled him to compete aggressively and favorably with George H. Bush in the beginning, but the sudden turn of fortune made him the closest governor to the White House from Massachusetts. Upon leaving office, he took full professorship at Northeastern University, and visiting professorships at University of California, Los Angeles as well as Loyola Marymount University. A devoted teacher apart, Dukakis has also committed himself to the strategic studies of Democratic election campaigns, and helped Deval L. Patrick win the gubernatorial election in 2006. He has been an “evergreen pinaster” in American politics.

The Dukakis economic policy took on a bold stroke during his second and third terms. His approach emphasized strong interference from the government and was known as “big government” and “industrial policy” in academia. The so-called “industrial policy”, as opposed to “technology policy”, refers to policies that provide direct fiscal and financial support to selected companies in specific industries. With the advance of new technologies and the increase of tax revenues, the aggressive Dukakis aimed at all-encompassing economic measures. The government stepped in to plan a number of industrial parks and went as far as to propose the slogan “if you need help, ask.” These practices invited challenges from the industry and the academia even in his heydays, not to mention more doubts and censure when the economy began to slow down in early 1989. Jeff Jacoby, a journalist from the Boston Globe argued that, “There never really had been a Massachusetts miracle. The state had outperformed most of the nation during the economic boom of the mid-1980s, but not because of any Dukakis wizardry. Its soaring growth had been powered by two engines: Proposition 21/2, the 1980 property tax cut adopted by ballot initiative that lit a fire under the Massachusetts real estate market; and the Reagan-era military buildup, which pumped hundreds of millions of dollars into Route 128, the high-tech highway ringing Boston…” The “miracle” argument failed to send Dukakis to the White House; worse still, it was derided by George H. Bush as “Massachusetts Mirage”. Dukakis spent the latter half of his third term in pain and remorse.

Dukakis, aggressive and upbeat, retreated under the onslaught of Bush senior

(From http://www.johnpratt.com/items/docs/lds/meridian/2003/parallel.html)

(From Spokane Chronicle, July 14, 1989)

Dukakis’s political legacies cover at least four aspects: encouraging and supporting the cooperation of production, study and research; developing public transport system (Dukakis himself takes the subway to work every day); promoting the advance of multi-industries in industrial parks; and championing the Boston urban revival. Dukakis blamed his own faulty strategies for losing the campaign, as he chose not to fight back forcefully George H. Bush’s malicious attacks. Even in the 2011 interview, he was still full of self-reproach and regret, saying that his failure to contain Bush senior and the subsequent resurgence of Republicans led by Bush junior had been the root cause for America’s crisis today. Despite its arguable truthfulness, Dukakis deserves our sincere respect for his strong sense of duty.

* * *

William Weld was probably one of the most popular governors in the history of Massachusetts. He first took office amidst the state’s turbulent economic times; yet when he sought reelection in 19994, he won with an impressive 71% of the vote. His coming to power as well as his outstanding performance introduced the golden age of Republican governorship in the Commonwealth. It lasted for sixteen years until 2007 when Democrat Deval L. Patrick took over.

The “real miracle” was credited to Weld, who resolved Massachusetts’s fiscal crisis and handled a staggering deficit of 800 million dollars he inherited from Dukakis. The Wall Street Journal and the liberal Cato Institute respectively named him as the “most courageous” and the best governor in America. He fulfilled the promise he made during his 1991 inaugural speech about “a leaner and more entrepreneurial state government.” When he left office in 1997, the number of state employees was downsized by 15, 000 from that of 1988. It was during his term that the Massachusetts economy as represented by Route 128 gained new life, which took the academia and business world by surprise. While propaganda about the “Massachusetts Miracle” did not survive its namesake book in 1988, scholarly prediction of Massachusetts’s decline failed in a similar manner in 1994. Route 128 must have embarrassed quite a few politicians and economists.

However, perhaps even to his own surprise, Weld’s political life following Massachusetts was unusually rough. It almost seemed like he had exhausted his good fortune in the Bay state. Soon after ending his governorship, Weld was nominated United States Ambassador to Mexico by President Clinton. Yet he never made his trip, for the Senate simply disregarded the nomination. This was mainly due to opposition from Chairman Jesse Helms of Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, who disapproved Weld for his moderate stance on several social issues. It was also partly attributable to a long-standing grudge Weld generated when he served as U.S. Attorney of Massachusetts. In 2005, Weld officially announced his candidacy for governor of New York in an effort to return to politics. Unfortunately, he was persuaded to withdraw one year later because he had picked the wrong partner, the candidate for lieutenant governor. From then on, Weld resigned himself to the private sector, and occasionally flirted with thriller novels and acting.

From endorsing Obama to backing Romney, Weld finally returns to the Republican family

(From http://www.wbur.org/2012/08/28/weld-romney-convention)

Maybe Helms, a fellow Republican, did have sufficient reasons to doubt Weld’s political inclination. In the 2008 presidential election, Weld initially supported Romney in the Republican primaries and later endorsed Obama for presidency. The two people he had voted for are both in the final race this year. Who would Weld choose? The suspense was just announced: he formally expressed his backing of Romney at the Republican National Convention! In fact, United States parties do not have hard and fast rules on their members. It is generally a matter of personal choice to decide on whom to vote, and the choice would not affect one’s public image. A once most promising politician in Massachusetts had resort to such means to gain public attention— what a pity!

* * *

Mitt Romney’s political path can be described as “rocky and bumpy”. After losing the 1994 U.S. Senate election in Massachusetts, he “exiled” to Utah where he successfully managed the 2002 Winter Olympics and Paralympics in Salt Lake City. In 2003, he returned to Massachusetts as governor and served one term. His 2003 presidential campaign had a good start, but failed to beat McCain. Since early 2011, he has withstood a variety of challenges and devoted himself to the 2012 election. Will he realize his dream this time at last? The result is to be revealed in a few weeks.

Romney defeated his democratic opponent and became the 70th governor of Massachusetts in 2003, continuing Republican’s governorship record in the state. There was a bit of luck in it- Romney did not actually attend the primary. Then incumbent female Republican governor, Jane Swift, was plagued with political missteps and personal scandals, and thus opted out of the party’s nomination. Romney, in contrast, was enjoying boosting reputation and popularity thanks to the success of the Salt Lake City Olympics. With the support from both prominent party figures as well as the White House, he was inarguably the best choice for Republican nomination. It is notable that Swift, being the only female governor in the state history, was reported to be pregnant during her campaign. Much controversy as the news invited, it turned out unexpectedly a favorable element for her election. Working mothers loved her! However, the child issue also incurred plenty of criticism. She asked her staff to babysit her daughter, and on one Thanksgiving, she used a police helicopter to fly home to care for her sick child. When these personal matters were exposed, women voters who had supported her went outraged so much so that toward the end of her term, she had “the dubious honor of a single-digit approval rating.” Ironically, for Swift, both success and failure boil down to “the child”.

There was nothing remarkable during Romney’s governorship in the Commonwealth. Confronted with attacks from his predecessor Dukakis and his successor Patrick, Romney intentionally distances himself from Massachusetts. During his term, the state showed weak economic performance and saw a surging unemployment rate. His personal success in business and previous contribution to the Olympics did not bring much benefit to the local economy. Romney’s financial expertise is undeniable, which he maneuvered skillfully to solve Massachusetts’ fiscal problems. Instead of raising taxes, he increased a number of fees. Although he avoided following Dukakis’ steps and kept his inaugural words, criticism raved. Anyways, he was running out of choices to fix the state’s colossal fiscal deficit, and he did manage to balance the book. However it was done, it was done.

Will the swaying Romney stabilize himself after the official nomination?

(From http://www.thehindu.com/news/international/article3843341.ece)

Romney’s greatest political achievement is the Massachusetts healthcare reform. Popularly known as “Romneycare,” it has transcended partisan politics in essence. As Romney himself acknowledged, “There really wasn’t Republican or Democrat in this. People ask me if this is conservative or liberal, and my answer is yes. It’s liberal in the sense that we’re getting our citizens health insurance. It’s conservative in that we’re not getting a government takeover.” Ironically, Romney was reluctant to claim the credit when Massachusetts celebrated the sixth year anniversary of the reform. Apart from its obvious contribution to improving people’s healthcare standard, the reform has boosted rapid developments in at least two industries—health care and health insurance. Massachusetts has become the global leader in biomedical researches, and the second-time host for the Biotechnology Industry Organization convention since 2007. Renowned European companies flocked in to base themselves in Greater Boston, as a direct result of the successful health care policies. Well-equipped with six years’ rich experiences, two big local insurance companies– Tufts Health Plan and Harvard Pilgrim Healthcare—are planning to explore new markets in other states. However, because of its striking resemblance with Obamacare, Romneycare has to be excluded from Romney’s trump cards, the action itself provoking ridicule and challenges. Is it a shrewd tactics or a miscalculation? Any judgment is too early to pass.

* * *

Needless to say, Massachusetts’s economic performance and industrial development have been closely related to the economic policies of the federal government in different periods. This could be a deserving reward for its active role as a major state and its continuing support for a strong federal government ever since the founding of America. Taking the building of high-tech Route 128 for example, much of the construction was funded by the federal government. The R&D funds of MIT and other scientific institutes came from the defense expenditure and basic research investment. The present governor Patrick, a close follower of Obama, also obtained generous funding for education, science and technological development. In retrospect, the federal government’s timely windfall also explained the two Republican governors’ (Weld and Romney) seemingly effortless solution of the fiscal crises. Yet Massachusetts’s statesmen certainly have greater ambitions than gaining support and benefit for their own state; rather, they aim at a larger stage to showcase their talents.

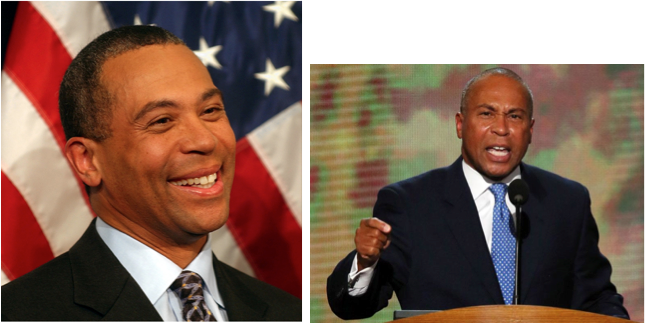

Aspiring Patrick has been gaining momentum

(From http://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2012/09/04/deval-patrick-tells-convention-mitt-romney-failed-massachusetts/o9iVjIOIBx5WNNTPXNsZsL/story.html)

Looking at the remorseful Dukakis, disillusioned Weld, undecided Romney, and triumphal Patrick, I was wondering just how far the Beacon Hill is away from the white house. The reflection put me in mind of a chat I had with a middle-aged white businessman in Newton two years ago. He raised a direct challenge about Obama: “Has he (Obama) ever run a government, or a business?” When I answered no, he smiled, “ then how on earth can he become a good president?” After a moment’s silence, he added jokingly, “our present mayor (Setti Warren) and governor (Deval Patrick) are both African Americans and they are doing pretty well. Perhaps Obama is just not dark enough.” His vote will definitely go to Romney this year, but the increasingly more conservative Romney has a slim chance in Democrat-dominated Massachusetts. Having always kept a close eye on the presidential election, I could not help thinking: success or failure, what is really at stake for Obama or Romney?

How far is it from the gold dome on Beacon Hill to the White House?

It is fair enough to say that an American political post, be it the president, the governor or the mayor, does not grant much power but is always subject to balances and checks. Such, though, never discourages elites from eagerly going for it when the election season draws close. The competition is extremely fierce. Once the election is over, the winner takes office whereas the loser returns to a peaceful life after congratulating his old rival. They either resign for good or start preparing for the next run. In both scenarios, they would have a proper and decent placement. Although U.S. elections at all levels have been scandalized by “money game” and mutual attacks between candidates (on which Obama offered a surprisingly honest reflection in his acceptance speech at the Democratic National Convention: “I know that campaigns can seem small, and even silly. Trivial things become big distractions. Serious issues become sound bites. And the truth gets buried under an avalanche of money and advertising. If you’re sick of hearing me approve this message, believe me – so am I.”), to contend in campaigns as such means intensity without violence, and to engage in “officialdom” like this means occasional disappointment but not permanent failure. Politics can become a choice for life– one can advance in full force or retreat with full honor. Triumphs or defeats, which could have made a roller-coaster trajectory of experience for politicians of other countries, are thus becalmed and consoled for the candidates in the United States. It is what I call: a political life filled with ups and downs yet never in lack of ready exits. We can well speculate: Individually, what one pursues has gone far beyond power itself. Is it pride, honor, duty or self-fulfillment? One can hardly know for sure unless being part of it.

Last weekend, I took my daughters to Gloucester for a folk art event. When driving through the north portion of Route 128, I could not help but think of the several political figures aforementioned. All of a sudden, my elder daughter asked me, “Dad, where are we going?” “To the White House.” I blurted out. Both she and I paused at my response and then laughed out at the same time! The hearty and loud laughter lingered long over the 128 highway…

References:

Center on Women and Public Policy Case Study Program. “Jane Swift: Motherhood in the Massachusetts’ Governor’s Office.” Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs, University of Minnesota. <http://www.hhh.umn.edu/centers/wpp/pdf/case_studies/jane_swift_motherhood/janeswift_case.pdf.> September 7, 2012.

Cooper, Michael. “A Candidate’s Sudden Turn from Prospect to Dropout.” June 7, 2006. <http://www.nytimes.com/2006/06/07/nyregion/07weld.html?_r=1&ref=williamfweld>. September 4, 2012.

Epstein, Jonathan. “Dukakis Speaks on Political Climate.” October 11, 2011. < http://www.thejustice.org/news/dukakis-speaks-on-political-climate-1.2641138#.UEai-UQ739B >. September 5, 2012.

Gaines, Richard and Michael Segal. Dukakis: the Man Who Would Be President. New York: Avon, 1988, c1987.

Hayek, Friedrich A. von. The Road to Serfdom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1944.

Jacoby, Jeff. “Bill Weld’s Revolution that Wasn’t.” City Journal. Winter 1996. <http://www.jeffjacoby.com/6043/bill-welds-revolution-that-wasnt>. September 4, 2012.

Kenney, Charles and Robert L. Turner. Dukakis: an American Odyssey. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1988.

Kilborn, Peter T. “In His State’s Success, Dukakis Seeks His Own.” The New York Times. August 5, 1987.

Kranish, Michael and Scott Helman. The Real Romney. New York: Harper, 2012.

Romney, Mitt. No Apology: the Case for American Greatness. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2010.

Saxenian, Annalee. Regional Advantage: Culture and Competition in Silicon Valley and Route 128. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994.

Senne, Steven. “Palin’s regard for Jane Swift changed in a swift manner.” June 12, 2011.http://www.boston.com/news/politics/articles/2011/06/12/palins_regard_for_jane_swift_changed_in_a_swift_manner/. September 9, 2012.

Taylor, John B. “The Road to Recovery.” City Journal, 22.3. (Summer 2012). < http://www.city-journal.org/2012/22_3_friedrich-hayek.html>. September 5, 2012.

A Chinese version of the article can be found at Sina Financial and Economics Blog.