Introductory Essay To My Creative Portfolio

ø

The six pieces I created for this class are all expressions of emotional reactions I’ve had to what we’ve been exposed to over the course of the semester. I have engaged with the themes of the course, and I examine them through my artwork, but these pieces are not just works meant to explicate some point or specific trope and idea. They are the result of emotional reactions I’ve had while immersed in the ideas of the course, they come from a place of individual experience and authenticity, and so they say something about myself as well as about what we studied. The main themes that arise in my artwork are: the difficulty of genuinely engaging with religious traditions other than your own, the difficulty and also the value of truly putting yourself in another’s shoes and understanding their experience; the experience of the martyr; the pursuit and enjoyment of the love of God. Each piece makes its own claims and seeks to move the viewer in a different way, but these themes I’ve realized inform all my art because they are central to my thinking and my experience in the course.

One of the main themes I explored with my creative portfolio is the love of God. I did this through constructing a Ghazal with traditional themes involving the search for God, the Sufi journey of the self to union with God, and the use of wine and intoxication as a symbol for the overwhelming love of God. I had already written a Ghazal for the Ghazal project, but that Ghazal dealt with less traditional themes and so I wanted to write a Ghazal more true to the genre. Although I am of a different faith, I felt an immediate connection with Sufi practice and theory because it is all about connecting with the love of God. The desire for God, the search for him and ones efforts to become more intimate with him, although pursued with perhaps different methods, practices, and theological frameworks, seemed to have significant similarities across religions that speak about the love of God. I was able to connect with this Sufi desire and see the value of their goal, even though I am from a different faith tradition. The love of God is absolutely central to all followers of Islam, especially the Sufi, and it was this that I tried to express through the Ghazal. I tried to express how essential it is to look for God’s love and how unfortunate it is when people don’t see the value of this pursuit and don’t search after that love. This is a theme we’ve seen the whole course through, and I was glad to take the opportunity to explore it more in my creative Ghazal.

The next significant theme of my art portfolio is the story of the martyr. The narrative of the martyrdom of Hussein was very appealing to me, as it is about a man who believes so strongly in the truth that he goes knowingly to his death rather than capitulate to the forces of evil. It is a powerful story. I found it extremely interesting how this story, with Hussein the martyr and Yazid the evil tyrant, has been used throughout all of Islamic history to establish narrative and moral context in situations of oppression. If there is a tyrant somewhere he is Yazid and he is crushing the spirit of his people, Hussein. It is such a powerful vocabulary of shared understanding within Islamic societies. I love the idea of the power of narrative portrayal. With my painting of the martyrdom of Hussein I tried to express both the significance of Hussein’s individual story, as the last great light and fire of the family of the prophet, as well as the enduring significance of his story as a means of inspiring people who are struggling against oppression.

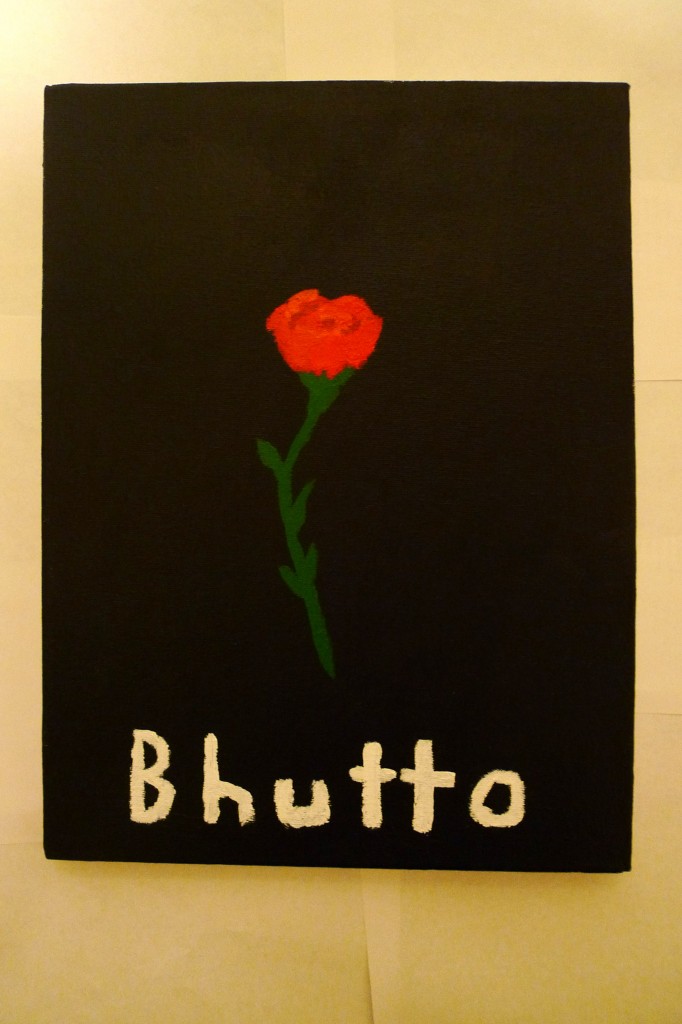

Similar to my work about Hussein is my work memorializing Benazir Bhutto. I describe in my post of the interpretation of “A Rose for Benazir Bhutto” that I have an interesting individual connection to this famous woman, both through our Harvard connection and how my dad met her once, but the main thematic significance of the work is how it celebrates her as martyr. Depending on your perspective Benazir Bhutto can fit perfectly into the Hussein narrative as the courageous champion of a more liberalized, accessible economy during her time as prime minister who was martyred by assassination upon her triumphal return to Pakistan. There are of course others who would invert the narrative and portray her as Yazid, pointing to her problems with corruption and secular influence, which only further emphasizes the plasticity and utility of the Hussein/Yazid narrative. There is just something so powerful about the martyr narrative that makes an individual into a historical force after their death even if when they were alive they were in no ways a paragon of perfection. This fascinated me, and that’s why I painted pieces on Bhutto and Hussein. Although my own perception of Bhutto leans far more towards the positive, I think it is important to be critical of the legacies of martyrs and not let the sheer power of their cult of personality overwhelm all criticism. This leads to an interesting juxtaposition of Bhutto and Hussein, as Hussein is a religious figure, a grandson of the prophet, viewed by Shias as the true Imam at the time of his death and also revered by Sunnis, and for whom a critical appraisal is much more difficult than for Bhutto who was a recent and colorful political figure. Anyone can agree to be critical of Bhutto’s legacy, but is Hussein’s legacy open to criticism? Especially considering his Imam status and the significance of the Imam I think there are those within the Shia tradition who would categorically deny any attempt at historical criticism, but there are others who would think historical criticism of him productive. That being said, my works engage with him as a true paragon and exemplar of martyrdom and don’t lean towards critique, but it is an interesting point when other more contemporary and less perfect martyrs are compared to him.

The most important theme of my artistic portfolio is the engagement with the other. The first piece I created was a poem called “Stranger” that spoke to the difficulty I had in approaching the Adhan. I had at first set out to record my own version of the Adhan. My motivation was that I did not like what seemed to be the prevailing style of Adhan recitation, which I think of as very melismatic, using a great deal of oscillation and variation of notes around every syllable. The Adhans we listened to sounded painfully warbly to me, and also dominated by nasality. I was very unsatisfied, and although I didn’t actually think I could do a better job reciting the Adhan than those who did the recordings we listened to, I did think that I could do it in a more pleasing style. I was going for a clearer, less nasal version that only had one or two notes per syllable of text. I knew this would be a difficult project but I didn’t realize how difficult. Most of the difficulty would have come from perfecting my own technique, especially considering that I have no vocal training, but I didn’t even get that far. The moment I began going through the Adhan and preparing to recite it, I became uneasy. The Adhan is a profound statement of belief, a statement of beliefs that I do not hold. I am not Muslim, I am Christian, and I do not believe that God is one or that Muhammad is his prophet. I thought that I could just recite the Adhan and it wouldn’t mean anything, but my visceral reaction to the attempt made me realize that, even alone in my room, my spoken word has meaning. I could not escape the sensation that it felt wrong to say things I did not believe, as it would both trample on my own beliefs and it would be disrespectful to the Islamic tradition for which these words are of devout significance. I could not say the Adhan without being uncomfortable, and I realized it was because of the powerful, inescapable meaning inherent in spoken word. My discomfort gave me insight into how difficult it truly is to put oneself in the place of another, to actually live out another’s beliefs and not just ponder them intellectually. I also realized that, in being made aware of the power of the spoken word, I was absolutely engaging with the Islamic tradition of recitation. For Muslims the Koran is most powerful as a spoken document, rather than a read one, and although I found it too uncomfortable to actually recite the Adhan, I experienced the power of the spoken word that is so central to how Muslims engage with their faith. It was also significant in that it gave me a chance to think of preference, in this case musical, and in how my preference is shaped by my background and that it presents a real barrier to me engaging with the art of people from backgrounds with different preference. Overall what I got from doing this first piece of art was an appreciation for the difficulty of truly engaging with the other, and also the beginnings of the value of benefit of the attempt.

My third piece was a plot summary that tells the story of two boys who go skiing and witness an act of violence and hatred towards Muslim immigrants. With this piece I was trying to express in narrative form the positives and negatives of when two cultural and religious worlds come together. The two American boys witness a sad and demeaning act of violence done to Muslim immigrants that is partly motivated by anti-Islamic sentiment. I think narrative is a very powerful way of bringing out sympathy in people for others that are not like themselves. Narrative does this because a person, when immersed in a narrative, lives vicariously through the characters in the narrative. It is one of the truest forms of stepping into another’s shoes. I wanted to show this, both within the story as the two boys are witness to and affected by the violence they see, as well as for anyone experiencing the narrative. I chose to use a plot summary structure because it involves the reader in creating the narrative themselves. The reader fills in the gaps and actively tries to situate themselves in the persons described within the story. This project was part of my progression in thinking about how, in order for there to be positive dialogue between people of different faith traditions, there needs to be mutual sympathy for the painful experiences of others and a recognition of the value of others regardless of difference, and I think a powerful way to do this is through narrative. The narrative also highlights how important it is that people step up and prevent discrimination against minorities, that they not be passive observers and therefore enablers. This is how I tried to use narrative to explore engaging with the other.

My last piece was a comic, structured like a political cartoon, which pictured several protestors waving and shouting nationalistic slogans and telling a Muslim girl, clothed in a burka, to leave because she was Muslim. This piece represents the consummation of how I think about experiencing the experiences of the other. The inspiration for this comic was the video we were shown in class of protestors in California saying very hateful things to Muslims as they were going to a civic dinner. Watching this video was painful for me because the hate spewed by the protestors was so terrible. What they said was horrible, and it was horrible that they had taken it upon themselves to say that they represented what America ought to be. I felt so bad for the Muslim individuals, even children, who were meant to feel that they were evil or the problem and that they didn’t belong. They belong just as much as anyone else in America because America is a place for everybody, where no one should be excluded from anything based on creed. This was an experience that allowed me to most strongly put myself in the shoes of others because it was such a painful moment. I felt so sorry for the people getting shouted at and I didn’t want them to feel like they didn’t belong, but rather that they absolutely did belong. The feeling of exclusion is terrible, and I wanted to express this, the damage the protestors were doing, in a powerful and striking way. I thought a political cartoon, which relies on pithiness and an immediately relatable punch line, would be the best way to do this. In the comic we see the effect of the hate on the girl in the burka, we get her inner voice and feel her pain. The absurdity of the protestors is also laid bare. My comic represents the strongest emotional connection I’ve felt with those of such very different backgrounds and experiences that we’ve studied in this course. I felt pain because of what they had to go through, and it was definitely one of the most powerful moments for me in the course.

With these creative projects I’ve explored what has been most significant for me through the course. The significance of these themes of engaging with the other, martyrdom, and the love of God became more apparent to me as I engaged them artistically. Instead of being analytic I had to create, and in creating I had to be sure that what I was creating was meaningful to me and interpretable to others. Using art as a medium for expression was especially important in how I thought about engaging with the other because art is experiential, it was invaluable in helping me to understand and identify with the experiences of Muslims, and if I had just been asked to write a paper on the experiences of Muslims in the United States or elsewhere I would not have had as powerful an experience. This art is my truest response to what I’ve learned in this class, not passive reception but an enriching and active immersion.