The Internet is Frying Our Brains?: Keep Calm and Carry On with Research Please

Comments: 6 - Date: February 27th, 2009 - Categories: Information Overload, Uncategorized

If you just skim the headlines, it seems like we might be screwed: “Social websites harm children’s brains: Chilling warnings to parents from top neuroscientist,” “Facebook and Bebo risk ‘infantilising the human mind: Greenfield warns social networking sites are changing children’s brains, resulting in selfish and attention deficient young people,” “Oxford Scientist: Facebook Might Ruin Minds” or going straight for the punch, “Is Social Networking Killing You?”

Got your attention? These articles were based on an interview with Oxford neuroscientist Lady Susan Greenfield with the Daily Mail, in which she put forth some hypotheses about online social interactions and fractured attention spans. Similar concerns about youth and their reliance on digital networking have been trotted out by the press and in books on several occasions, but Lady Greenfield’s prominence in the neuroscience has merited her substantial coverage. The crux of her argument is this:

If the young brain is exposed from the outset to a world of fast action and reaction, of instant new screen images flashing up with the press of a key, such rapid interchange might accustom the brain to operate over such timescales. Perhaps when in the real world such responses are not immediately forthcoming, we will see such behaviours and call them attention-deficit disorder

As a neuroscience student, I tend to approach articles about the brain with my critical scientist hat on, so while reading the previous linked articles, I kept looking for evidence backing up these claims. I found none. In Greenfield’s quote above, her language clearly shows that she is too only speculating about the harmful effects. This is fine – it’s how science moves forward: we put forth hypotheses, but we have to test them before coming to conclusions. In a follow up interview with The Guardian, she admits this too. (audio)

Interviewer: Is this based on your suspicions, Lady Greenfield, as a leading neuroscientist or is it based on evidence that’s actually been collated?

Greenfield: No, the whole point of my making this speech in the House of Lords is to draw attention to this issue and to hope that people will start to set up investigations.

I am entirely behind the hypothesis that increased social interactions online is changing the way our brains process information, but there hasn’t been enough research to corroborate these claims. Many of the issues Lady Greenfield brings up have been dealt with in blog posts here on digital information overload, drawing on our own experiences and what little research that has been done. But for newspapers to be running such inflated headlines that mislead readers into believing neuroscientists have actually proven such effects is nothing but alarmist.

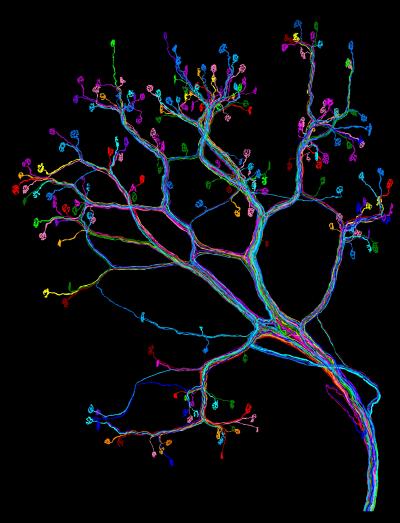

To put into perspective how wildly speculative it is to talk about “rewiring” the brain, as ars technica frames the issue, let’s see how much we already know about the wiring of the brain. Not much. The cutting-edge of connectomics – the study of how neurons are connected with one another – is being carried out by Jeff Lichtman here at Harvard using novel imaging techniques on the mouse brain. (We are nowhere close to being able to study the human brain with the same degree of detail.) Earlier this month, a paper was published with the first ever connectome, or neural map, from a mammalian nervous system. What this connectome (left) shows is all the neurons connected to one tiny muscle that controls the movement of a mouse’s ear (photo credit: HarvardScience). This is as much as we know so far of wiring in the mammalian brain. The human brain comprises an estimated 100 billion neurons, each of which connects to on average 7000 neurons. The simple understanding of the brain’s circuitry is a daunting task in itself, let alone understanding how these circuits develop. There are talented neurobiologists working on these questions – I happen to work in the lab of one of them – but we certainly not ready to make grand claims about the brain.

To put into perspective how wildly speculative it is to talk about “rewiring” the brain, as ars technica frames the issue, let’s see how much we already know about the wiring of the brain. Not much. The cutting-edge of connectomics – the study of how neurons are connected with one another – is being carried out by Jeff Lichtman here at Harvard using novel imaging techniques on the mouse brain. (We are nowhere close to being able to study the human brain with the same degree of detail.) Earlier this month, a paper was published with the first ever connectome, or neural map, from a mammalian nervous system. What this connectome (left) shows is all the neurons connected to one tiny muscle that controls the movement of a mouse’s ear (photo credit: HarvardScience). This is as much as we know so far of wiring in the mammalian brain. The human brain comprises an estimated 100 billion neurons, each of which connects to on average 7000 neurons. The simple understanding of the brain’s circuitry is a daunting task in itself, let alone understanding how these circuits develop. There are talented neurobiologists working on these questions – I happen to work in the lab of one of them – but we certainly not ready to make grand claims about the brain.

I definitely agree there are interesting questions that remain unanswered, allowing for plenty of room for potential research, even if this research won’t be easy. Longitudinal research on the long term effect of digital interactions will take years, even decades, before producing relevant data. Additionally these studies are incredibly hard to implement, as where do you get a control group of study subjects who never interface with a screen? Greenfield is right to ask for further research, but let’s wait for research before making solid claims. The issues aren’t exclusively for neuroscientists though – psychologists, policymakers, parents, even us digital natives, we all have a stake in this.

– Sarah Zhang