I’m getting married in a month. Life is good. And despite the best intentions of simplicity, our wedding seems to have become a huge undertaking. Although I don’t think that anything about planning an event or about getting married is fundamentally different because of digital technology, I have noticed a few trends and used lots of interesting tools in this process.

Communication (email and instant messenger):

I’ve been spending the summer here in Cambridge, MA working with the Digital Natives project. My fiancé is living in our apartment in Brooklyn, NY. Our families and friends want to help, and they are in Florida, New Jersey, and many other places. Email helps a lot. Instant messenger [Wikipedia] helps more.

98% of the planning we are doing starts online. Just about everything we’ve needed to find or to plan has started at a search engine. Almost every evening my fiancé and I are online working on doing something “productive.” While the merits of multi-tasking are certainly up for debate, the fact that we are “there” to bounce questions and ideas off of each other has been amazingly helpful in this context. We copy and paste URLs [Wikipedia], email to-do lists, and occasionally open up an audio or video chat for discussions that require more direct attention. Because of this, not being in the same room to plan together has become pretty much a non-issue.

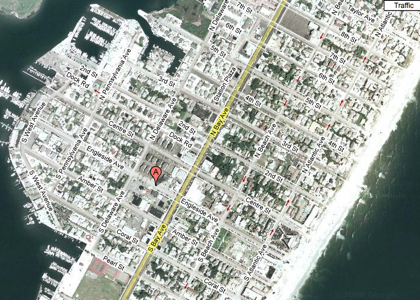

The Location (maps):

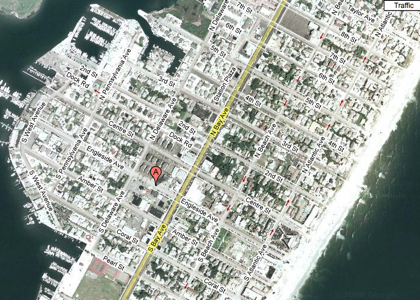

We decided to have our wedding on the Jersey shore, in a little shore town that I grew up vacationing at with my extended family (Exit 63). It feels great to stay true to my NJ roots and throw a wedding in NJ (you’d understand if you were from the Garden State).

Being that we are subway-riding city folk at the moment, we rarely have to worry about the mix of alcohol and motor vehicles. Obviously, the wedding was going to be a different story (The subway service in NJ is notoriously sub-par to, er, nonexistent). We really wanted to plan something where everything was walkable and everyone could celebrate as merrily as they desired to without having to worry about driving.

Using Google Maps and other similar map services, we were able to find a location for a rehearsal dinner, an outdoor pre-wedding barbeque, a location for the ceremony, and a hall for a reception, all within a few blocks of each other. While this would have been possible with a paper map, the combination of search engines and instant access to satellite images really helped us to feel out what we were planning.

Communication (the website):

Since most of our guests will be traveling to our wedding, and many of them looking for overnight lodging, we needed a way to help them find places to stay that were affordable, reputable, and in walking distance. We needed a way to communicate this information to our guests as it came in, both before and after invitations were sent. So, we built a web page and put a whole bunch of lodging options up there. While we were at it, we highlighted a bunch of “fun stuff to do while you are in town.” This is great because it gives us the flexibility to modify and update the information until a week before the wedding.

More importantly, textual links from our site to the lodging options and to the respective websites of other points of interest really harness the power of the Web, allowing users of our website to find all the information that could possibly need in just a few clicks.

We also used the “My Maps” feature on Google Maps to create custom maps of all of the points of interest, and linked those Google Maps from the entries on our website. This allows our guests to plan ahead a little and to really have a sense of space, helping us to keep everyone on foot and out of their automobiles.

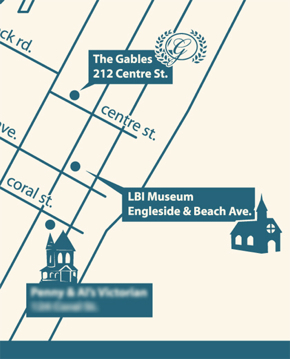

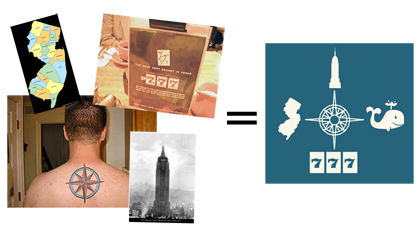

Invitations (the mash-up):

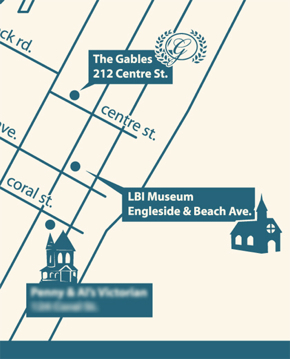

My suggestion of sending out email invitations was shot down (correctly) without much consideration. My suggestion of talking invitations with customized voice recordings (“Hey Joe! Come to our wedding! See you in September!”) was shot down (unfairly). In the end we decided to create our own invitations and have them printed. Because we want to encourage people to explore the little shore town, we decided to include a little map of the area.

Google Maps again to the rescue! I navigated Google Maps to the area, took a bunch of “screen captures” of areas of the map, and then stitched them together in Photoshop [Wikipedia], an image editor [Wikipedia]. We found Creative Commons-licensed images and icons on Flickr that really helped communicate the smart but chill vibe that we wanted too, even with my meager artistic skill. To make the map simple and iconographic, I traced the map in the vector graphics [Wikipedia] editor, Illustrator [Wikipedia], with the help our friend Del.

Then, we emailed a PDF [Wikipedia] off to the printer and sent them via the good old fashioned postal service.

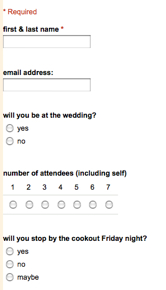

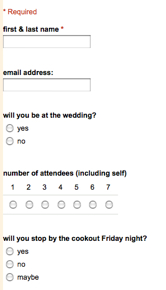

RSVPs (the semantic web):

My favorite part of this process so far is has been collecting the RSVPs. To keep printing (and environmental) costs down, and to keep our sanity, we decided to ask people to RSVP online. Although there are many methods of creating forms for websites [Wikipedia], Google provided the solution that was easy and met our needs. We created a spreadsheet in Goggle Docs, and then created a form that guests can fill out that dumps the data directly into the spreadsheet. Google Docs auto-generates the html code for the form, which we embedded into our website.

Wasn’t all of this a lot of work? Actually, no. It probably only took an hour. Opening and counting that many RSVP envelopes would have taken twice as long, and would have been a slow, cumbersome, and error-prone process in comparison. Better still, we get emails every time someone RSVPs, and checking out the notes people have written along with their RSVP a couple of times a day is a lot of fun.

The spreadsheet keeps running totals of guests and reception meal menu choices in real-time, and allows both my fiance and I to access it from our remote locations. We were able to invite the family members and friends who are helping us plan to view the spreadsheet.

Paying the Vendors (invoices & online banking):

Managing a budget for a wedding is tricky, but Internet banking has made it a lot easier. By using bill-pay services that both my fiance and I can access, either of us can arrange to send a check to a vendor at the click of a button. We can both have instant access to what is being paid when, and adjust our Google doc spreadsheet at the click of a button to make sure that we are still on track. Doing this on paper, or doing it over the phone, would have been vastly more difficult. [Wikipedia entry for Online Banking]

Paperless (contracts):

There are a few vendors’ relationships that require basic contracting. We could either wait for snail-mail, or buy a fax machine. Actually, we haven’t had a land-line phone in three years and rely exclusively on cellphones, so the fax wouldn’t work. However, internet fax [Wikipedia] services work well. (Checkout eFax or MyFax.) Because we have an account with a fax number, anyone can send a fax to us that will then arrive in our email inboxes as a PDF. It’s super convenient, and environmentally responsible to boot.

If someone needs to actually send us a piece of paper, we have it sent to our postal-to-email bridge, Earth Class Mail. Earth Class Mail scans all the paper that arrives in our PO Box and emails to the PDFs. (Earth Class Mail will also contact the senders of mail you identify as junk and ask them to stop sending it, saving countless pounds of junkmail from ever being printed.)

When we need to sign documents, I slap a digital signature [Wikipedia] on the PDFs. This makes and image of my signature appear on any print-out, and also helps to secure the file digitally, making my signature disappear if the file is modified after I sign it. When sending these contracts back I either email them, virtually “fax” them back using our fax service’s email-to-fax bridge, or have a good ol’ US Postal service paper copy sent to the destination via our email-to-postal-mail-bridge, Postful.

While the fax services are cheaper than owning and maintaining an actual fax machine and phone line, the mail services are more expensive than regular postal mail. In the end, the two are pretty much a wash, and we get the added benefit of having everything we need on-hand at all times from our laptops, having it from states away, and no clutter in our NYC-sized apartment.

…Using all of these various technologies certainly hasn’t changed the nature of the event itself. However, the technologies are helping us to plan a wedding more conveniently over a long distance, involving the people we want involved in planning to the exact degree that we want them involved, and getting surgical with a few of the details that we really care about, helping us plan an event that is more uniquely our own than would have previously been possible.

–John Randall