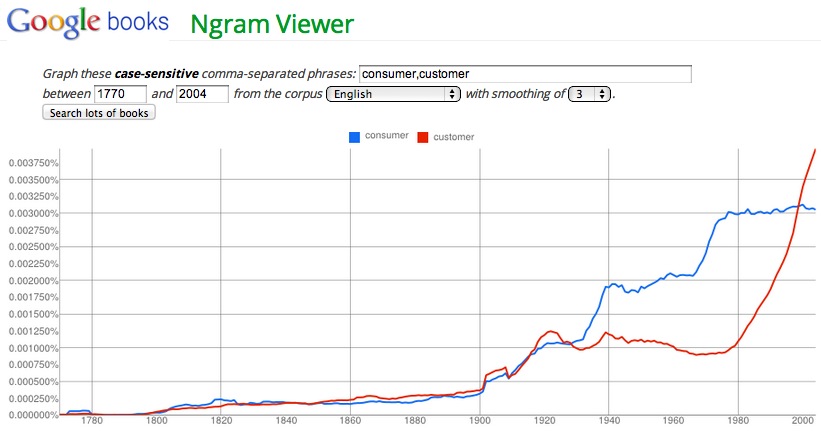

Out in the marketplace — that place where we do business as buyers and sellers — what and who are we, as individuals? Here’s a graphic that might help frame the what question:

It’s a Google Ngram that plots the prevalence of two terms — consumer and customer — in books between 1770 and 2004.

I suspect that the first little bump followed publication of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations, in 1776. The words consumer and consumers in sum appear forty-nine times in his text. The word customer appears four times. (Thanks to the Library of Economics and Liberty for making those searches possible.) Yet the two terms were used in about equal amounts through subsequent books, until the early 1930s, which was when mass marketing (with the help of broadcasting) began to prevail — and with it the sense that the masses, now generally called “consumers” were the populations that mattered. The term “customer” began to fall off for awhile there.

Things turned positive for customer in the mid-1990s, I suspect because the Internet and e-commerce showed up and got huge.

But both words are still with us, and are still usually used interchangeably.

Yet they do mean different things, and we should pull them apart.

Take Google, Facebook and Twitter, for example. Those companys’ consumers and customers are different populations. The consumers are the users. The customers are the advertisers. In fact, our consumption is what’s sold to advertisers. “If it’s free, then you’re the product,” the saying goes. It’s not exactly right, but it’s close enough to make some points, one of which is that your influence on those companies is far less than it would be if you were paying for services rather than merely using (or consuming) them.

On the who side, it helps to start with this fact: out in the brick-and-mortar marketplace, we are by default anonymous most of the time. That is, nameless. As it says in the Free Dictionary,

a·non·y·mous (

-n

n

-m

s)

adj.

1. Having an unknown or unacknowledged name: an anonymous author.2. Having an unknown or withheld authorship or agency: an anonymous letter; an anonymous phone call.3. Having no distinctive character or recognition factor: “a very great, almost anonymous center of people who just want peace” (Alan Paton).

[From Late Latin annymus, from Greek an

numos, nameless : an-, without; see a-1 + onuma, name (influenced by earlier n

numnos,nameless); see n

-men- in Indo-European roots.]

When we go into a store to buy a shirt or a screwdriver, or when we buy a meal at a restaurant, we usually don’t say “Hi, I’m Jill, I’ll be buying here today,” and the person serving us usually doesn’t call us by name, even after we’ve handed them a credit card.

In fact, the default protocol for merchants is to not to give special attention to the name on a credit card, because that card is for use in a payment protocol, not a social one.

Thus we tend to use names only when we need them, for example when the person behind the cash register at Starbucks needs to write a name on the paper coffee cup handed to the barista after you give your order. Or when we get into serious dealings, such as when we’re buying a car, and a personal relationship is required.

Note that when we do name ourselves, we’re the ones doing the naming. We don’t say, “Hi, the DMV calls me Paul,” or “The IRS calls me Cheryl.” We say, “I’m (whatever I choose to call myself).” The vector of identification goes outward from the self. The sovereign that matters, the one with sole volition, is the human self. Not an administrative entity. And not society, either. (Not unless we are a celebrity — meaning a person whose name and face are known to countless strangers, and who is therefore nonymous by default. Whether by intent or circumstance, the fact remains that celebrity is by nature a Faustian trade: anonymity is the price paid for fame. And it’s a high one. Even in polite places like Santa Barbara, where celebrities can wander about with a low risk of being bothered by strangers, people still notice. One is not anonymous.)

There is a distinction here too, and it is between what Moxy Tongue describes as one’s sovereign source and one’s administrative identities. One is ours, and the other isn’t. Put another way, one is human, and the other is calf-cow. In the latter we are the calves, and we are what the cows call us. I’ve written about this before; but the difference this time is that we’ll be gathering to talk about it, along with many other related subjects, at IIW, the Internet Identity Workshop, which runs Tuesday-Thursday of this week. Let’s pick up the discussion then. Moxy himself will be there to help lead the way.

Is there a connection between the customer/consumer distinction and the sovereign source/administrative one? That is, between what we are and who we are? Put them together and there’s a lot more to talk about. I believe there is much more autonomy and power to claim for ourselves — for the good of the whole marketplace — if we come to a broad understanding here.

Leave a Reply