Africa is already connected NOT by Facebook and Google

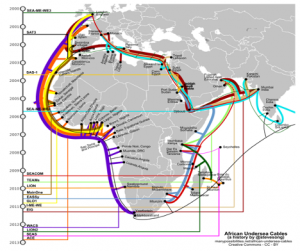

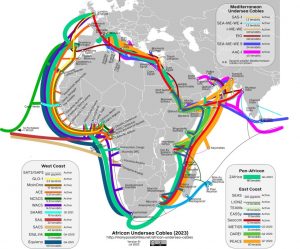

In the midst of the pandemic, Facebook (and partners) announced 2Africa a new subsea cable. About the same time last year, Google also announced a subsea cable called Equaino. It looks like they are trying to save Africa, but this is the problem – we have way too much capacity on the beach and not enough inland to connect to the wireless and cellphone networks to drive broadband to the masses. What Africa NEEDS today is terrestrial fiber to drive the existing subsea cable capacity inland to improve the broadband capacity of the wireless and cellphone networks. The diagrams below by Steve Song under the auspices of Many Possibilities gives you a historical account of Africa been connected to the world by subsea cables since 2001 through SAT3 – a consortium of majority Africa owned telecom operators. As per the second diagram Google and Facebook are building the 19th and 20th cables which would be live in Q4 2021 and Q4 2023 respectively. Hence Facebook and Google cannot be connecting Africa to the world in 2020 – at best their two new cables could serve as redundancy to the existing ones as well as provide capacity in the future.

In 2001, SAT3 and all other subsea cables were built through a club consortium which meant if you did not belong to the club you could not play. The club consortiums then set a high price tag for their fiber because they had a monopoly in the markets. In 2004 I started a movement under the auspices of the Ghana Internet Service Providers Association (GISPA) and Africa Internet Service Providers Association (AfrISPA) both of which I co-founded to dismantle these consortiums and monopolies with the intent to drive down the price of connectivity to make broadband more accessible and affordable. Our first victory was in November 2004 when GISPA signed an agreement with Ghana Telecom to reduce the cost of SAT3 by 1/3. GISPA then led the establishment of the Ghana Internet eXchange (GIX) to keep local Internet traffic in Ghana. AfrISPA members followed the GISPA lead and started negotiating for cheaper prices as well as building their local internet exchanges to keep Internet traffic within their countries.

In 2005, Russell Southwood, Anders Comstedt and I wrote “Open Access Models: Options for Improving backbone access in developing countries” for the WorldBank in which we presented an alternative approach to club consortiums and monopolies for the development of fiber networks. I followed this up in 2006 by writing one of two missives that made the case for “Open Access” communications infrastructure in Africa. Come 2007 I got invited by Dr. Bitange Ndemo to join the founding team that launch The East Africa Marine System (TEAMS) based on the open access model we had developed – a first in East Africa with Kenya as the nexus. 2009 saw the arrivals of the TEAMS and SEACOM cables which had Convergence Partners as one of it’s investors led by Andile Ngcaba who also led the launch of Africa’s first Dawn Satellite – by 2013 ten more subsea cables went live. According to Paul Hamilton of African Bandwidth Maps, Africa’s total subsea design capacity at 2018 was 226.461 Tbps with the sold international bandwidth at 10.962 Tbps, including subsea capacity at 10.470 Tbps and terrestrial cross-border capacity to submarine cables at 479 Gbps so the real challenge today is how to increase this terrestrial capacity.

As per the map above we have 18 cables with Google building the 19th and Facebook the 20th so the economic impact of subsea cables which Facebook funded RTI International to undertake should be attributing the impact to the existing cables and not the ones that are not yet in existence. Gillian Marcelle, PhD, Managing Member of Resilience Capital Ventures LLC who has had several decades of facilitating and mobilizing capital for the digital economy has this to say: “tackling connectivity across the continent and mobilizing positive economic and social outcomes must draw on indigenous expertise. The the days for us Africans waiting for a savior are LONG gone.” Based on her extensive investigations of African telecoms and tech industries, she went on to admonish recent efforts that render African knowledge and expertise invisible. She further added that there is considerable global and regional scholarly work that already goes much further than simple correlations between GDP, economic output and investments in connectivity enhancing projects. When asked about her key recommendations, Dr Marcelle offered this view: “Many advocates including those active in the global caucuses and multistskeholder partnerships have established conclusively that it is necessary to understand patterns of inequity and exclusion that arise from bottlenecks and blindspots. What is required now are smart and authentic partnerships that build on the foundation laid to produce tremendous positive outcomes. In Kenya, Ghana, Nigeria, Rwanda and South Africa there are ecosystems with components and actors to make good on this promise.”

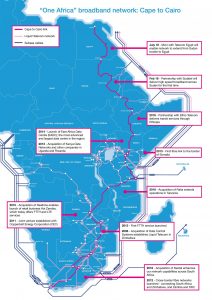

What Africa NEEDS today is terrestrial fiber to drive the existing subsea cable capacity inland to improve the broadband capacity of the wireless and cellphone networks. The problem they should be solving is not bandwidth to the beaches, but bandwidth to the Savannahs and jungles. Liquid Telecom which is part of the Econet Group owned by Strive Masiyiwa has been in the forefront of building terrestrial cross-border fiber networks across the continent – they have the most extensive network from Cape Town to Cairo but yet to cover West Africa as per the map below. We need three or four more of such networks to not only increase the capacity but provide competition to drive down the price of cross-border bandwidth. CSquared which counts Google as one of its investors is building metro fibers in Ghana, Liberia, and Uganda. Others like Wannachi Group in Kenya, DFA in South Africa, Smartnet in Zambia, Spectrum Fiber in Ghana, Phase3 Telecom in Nigeria, etc and in some cases the Mobile Network Operators (MNOs) are also building metro and national fiber networks.

We are also seeing the growth of data centers to host the applications being developed by digital innovators that drive consumption of the bandwidth being built. The African Internet eXchange System (AXIS) which was founded by AfrISPA and implemented by the AU is growing the Internet fabric by increasing the routing of local traffic on the continent. In Ghana the Internet Clearing House (ICH) by Afriwave Telecom is created the framework for deploying local value-added services that the government and other institutions can take advantage of – this would drive the growth of local content. As we know “content is king” so as we develop more localized African content that is hosted in the data centers and networks on the continent, we would need less and less international bandwidth. Hence my argument that Africa does not need additional subsea cables but rather more terrestrial fiber to improve the existing capacity whiles driving prices down to offer an amazing broadband experience.