‘Missing’ Images for Catalogs and Finding Aids

Written by Alice West

This post is the sixth in a series about the Stuart Cary Welch Islamic and South Asian Photograph Collection written by the project’s staff in the Digital Images and Slides Collections of the Fine Arts Library.

Previously, we talked about an important subset of Stuart Cary Welch’s photographs, images of Islamic and South Asian art in private collections. This time, we look at another interesting subset, the images that are currently available to the general public only as textual descriptions in catalogs or finding aids.

Libraries and museums maintain inventories of the objects they own. Some inventories are simple itemized lists, while others publish catalogs that provide descriptions of the objects. It takes an enormous effort to compile a catalog with descriptions, whether detailed or not. Compilation of library catalogs is a branch of art history in its own right, and some catalogers, such as Hermann Ethé, Lynda York Leach, or Basil W. Robinson, are known particularly for their cataloging accomplishments, in addition to their research. Catalogs of illustrated manuscripts are especially time and space consuming, as a manuscript may have dozens and even hundreds of images that need to be identified and described. As a rule, printed catalogs do not include images of all miniatures, as it would make the catalogs prohibitively large and expensive, especially for color printing.

Computer technologies brought a revolution in cataloging. They brought in virtually unlimited storage space, as well as powerful search capabilities. The first stage of this revolution was to convert existing paper catalogs into digital databases. However, due to the sheer scale of this task, many online catalogs are, in effect, scans of the old paper catalogs that have but a few images. Similar to catalogs, institutions compile finding aids that describe groups of objects in their collections, but provide little description of individual objects or images they contain.

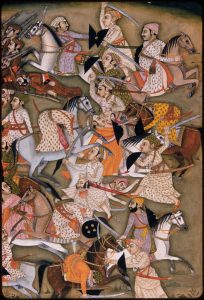

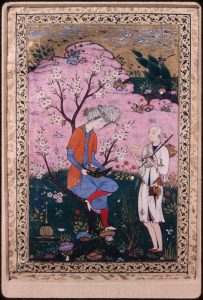

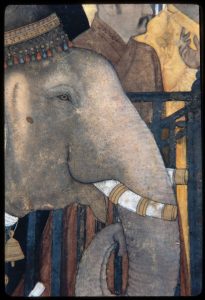

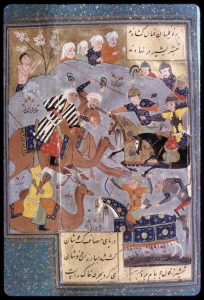

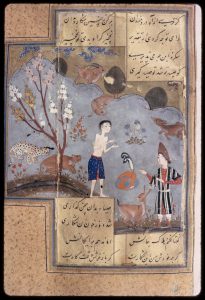

This is where the Welch Photograph Collection can help. It may contain the ‘missing’ images from catalogs and finding aids, such as the miniatures from Layli u Majnun (Ouseley Add. 137, Bodleian Library) detailed in Robinson’s Descriptive Catalog [i] (pic. 1 and 2) and Persian, Turkish, Hindustani, and Pushtu Manuscripts in the Bodleian Library by Sachau and Ethé (No. 650). Many leaves of this manuscript are damaged or entirely destroyed, which may explain why, given the limited resources, this manuscript has not been digitized. Still, its miniatures are well-preserved, and the Welch Collection provides an opportunity to take a peek at them [ii].

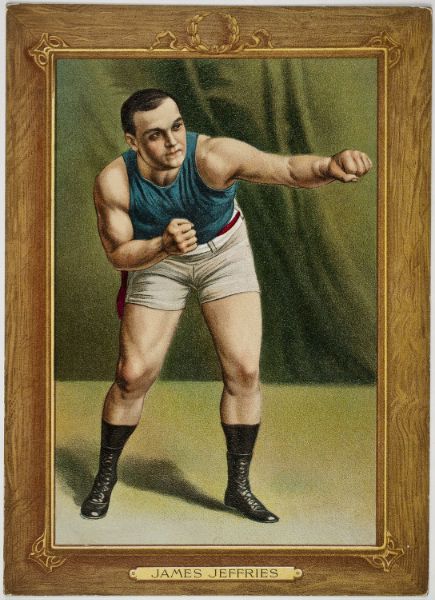

Pic. 1. Battle of the Clans. Layli u Majnun by Nizami Ganjavi, Bodleian Library, Ouseley Add. 137, ca. 1573-1574.

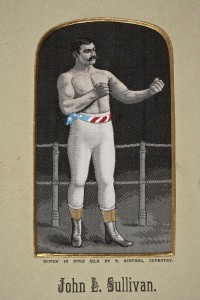

Pic. 2. Majnun Visited by a Friend in the Desert. Layli u Majnun by Nizami Ganjavi, Bodleian Library, Ouseley Add. 137, ca. 1573-1574.

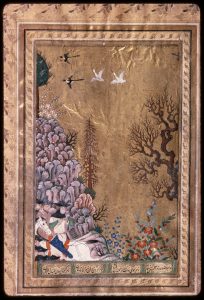

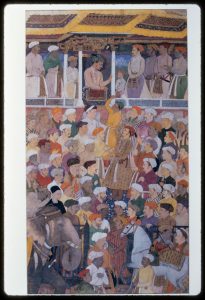

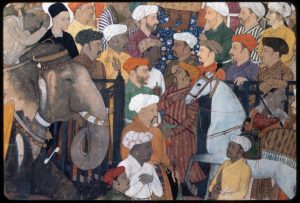

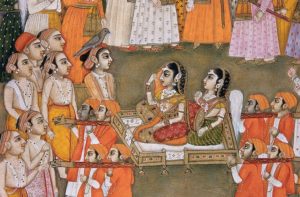

Dastur-i Himmat (ca. 1755-1760) is a lavishly illustrated West Bengali manuscript meticulously described in Linda York Leach’s Mughal and Other Indian Paintings from the Chester Beatty Library. According to the catalog, the Dastur-i Himmat retells in Persian verse the Hindu romance of Prince Kamrup of Avadh and Princess Kamalata of Serendip. The romance was very popular, but the Dastur-i Himmat was a minor version, not often produced. Leach’s large illustrated catalog contains 18 out of 231 images from the manuscript, both color and black-and-white. This is a relatively large number of reproductions for a printed catalog of this scale, but the Welch Collection has at least two illustrations that are ‘missing’ from the catalog: Kamalata and Kamrup with the magician Bidyachand disguised as a parrot on his head and a Battle Scene. Both of these Welch images are details rather than the full versions of the original images, though we are hopeful that their full versions, as well as other illustrations from this manuscript, will be discovered as we continue to catalog the collection.

Pic. 3. Kamalata is carried out on a litter, while Kamrup stands in a row of her suitors with the parrot Bidyachand on his head. Dastur-i Himmat, Chester Beatty Library, Ms. 12, ca. 1755-1760.

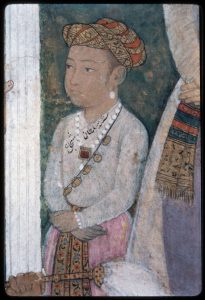

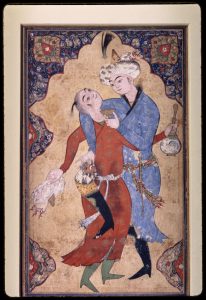

With its vast number of Islamic manuscripts and albums, the British Library has one of the most extensive digitization programs in the world. The Library’s fabulous online Johnson Collection, however, is a finding aid that provides detailed textual descriptions of its objects, but not images. Occasional images can be found elsewhere, including, for example, in the British Library’s Asian and African Studies Blog, but you can also look for some of the ‘missing’ images in Welch Photograph Collection, where they are preserved in high resolution, color, and occasionally close-ups. One such image is Young Prince Embracing a Youth (pic. 5a). This miniature belongs to the Bukhara (modern Uzbekistan) school of painting that had significant influence on Mughal art. There are multiple variations on this theme, including one at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (pic. 5b) and a 19th century image currently at the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia (pic. 5c). While not as widely known, Welch’s image from the British Library’s Johnson Collection stands out for its bright colors and unique style among alternative tinted drawing versions.

Pic. 5a. Young prince embracing a youth. British Library, Johnson 56,12. Bukhara school, late 16th century

Pic. 5b. Two youths romping. Iran (?), late 16th century. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1978.18.

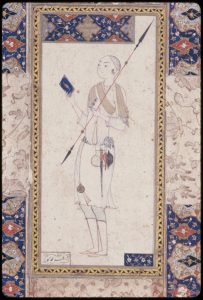

Another rarely seen miniature described in the Johnson Collection’s finding aid is Young Dervish with Spear and Book (pic. 6) by a renowned 16th century Khorasani artist Muhammadi, who, according to Abolala Soudavar, was “the uncontested master” who influenced the work of Farrukh Beg and Riza ‘Abbasi [iii]. This image was used in at least two later compositions, one of which, Young Noble and Dervish in Conversation from Aga Khan Museum of Toronto (pic. 7), has been reproduced in several printed museum’s catalogs, but not on the museum’s website. Digital versions of both images can be found in HOLLIS, Harvard’s portal to the Welch Collection.

Pic. 6. Muhammadi, Young dervish with spear and book. Iran, ca. 1575. British Library, Johnson 28,14

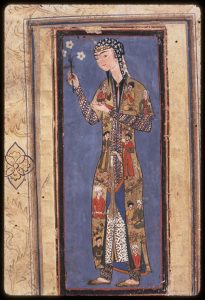

One of my favorite undigitized and understudied manuscripts is Shirin u Khusrau from Hamsa of Hatifi, nephew of the famous poet Jami (Codrington/Reade 244, Royal Asiatic Society). Fihrist Oxford-Cambridge catalog calls it “a manuscript of sumptuous quality,” and rightly so. This Khorasan style [iv] manuscript has only five miniatures and one tinted drawing [v], but its margins illuminated with waqwaq scrolls and human-inhabited cameos are delightful (pic. 8). Among the miniatures, one particularly stands out: it is a girl in a bright robe decorated with standing and sitting human figures (pic. 9).

Pic. 8. Waqwaq scrolls with five medallions of youths and girls. Khorasan, ca. 1575. Royal Asiatic Society, Persian 244, f. 3a.

Pic. 9. Standing girl holding a spray of flowers. Khorasan, ca. 1575. Royal Asiatic Society, Persian 244, f. 94b.

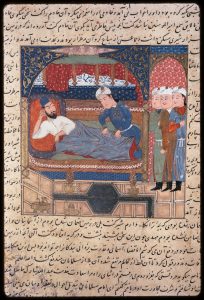

The Welch Collection has nine out of the 25 miniatures in Jawami al-Hikayat by ‘Aufi (British Library, Or. 11676), for which the British Library catalog provides only textual descriptions. One is particularly lively, showing the Abbasid Caliph al-Mahdi (8th century), who is unable to sleep, and his masseur working on caliph’s legs and simultaneously entertaining him by telling stories. Note the intently listening king, the masseur, who applies visible force to do a good massage, and a number of golden metal objects in the foreground, including a wash basin with a ewer and an incense burner to help the caliph relax.

Pic. 10. The Calif al-Mahdi and his masseur. Khorasan, ca. 1575. Royal Asiatic Society, Persian 244, f. 94b.

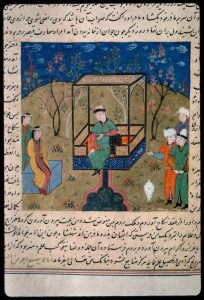

Many images in the Welch Photograph Collection come without notations, so the Fine Art Library’s catalogers rely on manuscript descriptions in catalogs to identify the images. Problems arise when more than one description matches an image. For example, the miniature in pic. 11 from Jawami al-Hikayat matched two descriptions from the catalog [vi]: 1) f. 381a: The four travelers being tested by the Indian princess, and 2) f. 278a: Princes of Rum is talking to her tenth suitor. Luckily, a few lines of text that came with the image helped identify it as folio 278a. This serves as an example of the importance of text that comes with the image, which, unfortunately, is often cut off in reproductions.

Pic. 11. Princes of Rum is talking to her tenth suitor. Iran, early 15th century. Jawami al-Hikayat, British Library, Or. 11676, f. 278a.

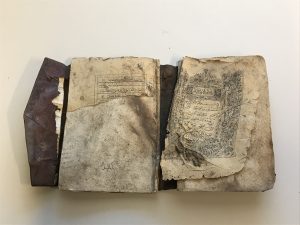

I would like to end this overview with a stunning miniature from the Keir Collection, currently at the Dallas Museum of Art, but not on the museum’s website. Its description, along with a color reproduction, appears in a rare printed catalog of the Keir Collection [vii]. The expanse of the gold sky that takes most of the painting makes this image especially beautiful. The unusual composition, as well as the ‘cut off’ figures in the lower left corner make researchers believe that it was cut out of a larger image [viii] or is part of a two-page frontispiece.

Supplementing catalogs and finding aids with color images was not Welch’s goal, so there is no systematic coverage even for major publications. If an image is missing from a particular catalog, there is no guarantee you will find it in the Welch Photograph Collection. Still, you may want to try searching HOLLIS or ask the librarian in charge of the collection, Nicolas Roth (nicolas_roth@harvard.edu).

Images that have been described in catalogs, but have not been available visually until now, provide additional material to study and may even inspire new research. One thing we are sure about: the Welch Photograph Collection holds many pleasant surprises for its visitors, both academic and general, as the work on cataloging the collection continues.

Bibliography

[i] B.W. Robinson, A Descriptive Catalogue of the Persian Paintings in the Bodleian Library (Oxford: Clarendon, 1958), 1027-1035.

[ii] B.W. Robinson, Catalogue of a Loan Exhibition of Persian Miniature Paintings from British Collections, VAM (London: s.n., 1951), 80.

[iii] Abolala Soudavar, “The Age of Muhammadi,” Muqarnas 17, no. 1 (2000): 53-72.

[iv] B. W. Robinson, “Muhammadi and the Khurasan Style,” Iran 30 (1992): 17-29.

[v] B. W. Robinson, Persian Paintings in the Collection of the Royal Asiatic Society (London: Royal Asiatic Society, 1998), 59-61.

[vi] Norah Titley, Miniatures from Persian manuscripts: catalog and subject index (London: British Museum, 1977).

[vii] B.W. Robinson, Ernst J. Grube, G. M. Meredith-Owens et al., Islamic Painting and the Arts of the Book. The Keir Collection (London: Faber, 1976).

[viii] B.W. Robinson, Persian Miniature Painting from the Collections in the British Isles (London: HMSO, 1976).