If you follow publishing news like I do (I own a small publishing company that specializes in how-to guides and technology cheat sheets) you have probably heard about Amazon’s misguided policy change from a few years ago that allowed third-party sellers of books to “own the buy box” on publishers’ book listings. I predicted at that time that it would attract a wave of counterfeit books, which has proven to be true. But I didn’t anticipate another kind of cheater: Third-party book sellers passing off used books as new.

Amazon opened the buy box to booksellers in 2017. It said that it was following the same policy that was used in other parts of its marketplace, which allows third-party sellers to control the buy box on product listings if they offer the product at a lower price than the official source, which is usually the manufacturer or distributor.

Publishers immediately cried foul. This statement from the Independent Book Publishers Association outlines the concerns of independent publishers (disclosure: I was an IBPA board member at the time and gave feedback on early drafts).

The types of books most likely to be pirated

As an Amazon FBA seller of other types of goods (namely, genealogy charts and forms) I knew very well the threat posed by counterfeits. It’s a long-standing problem that has attracted lots of negative press (“Amazon May Have a Counterfeit Problem“, “Leveeing a Flood of Counterfeits on Amazon“, “How counterfeits benefit Amazon“) and impacted my company, which was forced to invest in Amazon’s anti-counterfeit service Transparency.

For an example, one publisher, Bill Pollock of No Starch Press, reported repeated incidents of counterfeit books being sold by Amazon. The first reports surfaced in 2017, and earlier this month it happened again.

I have been impacted by another problem that IBPA predicted: Third-party sellers flogging used books as new. It’s actually a far bigger problem for me than counterfeit books, and I now pay an independent contractor to help me monitor my own listings.

Here’s what I think is happening:

Publishers or Amazon sellers who have products that are easy or cheap to copy and have high list prices have the most to lose with the Amazon buy box policy. There is a real risk of pirates taking over listings with counterfeit, low-quality copies. Potentially, they will have to deal with third-party sellers passing off used goods as new.

My company publishes IN 30 MINUTE guides and cheat sheets. They are relatively low-margin and have a low retail price – $11.99 to $12.99 for most books, $6.99-$7.99 for the cheat sheets. Yes, they could copy the books, and do some cheap digital short runs to get bogus inventory into the system, but because my list prices are already so low I don’t think they could make much. The pirates know this, and tend to go for higher-priced titles (including textbooks) from other publishers. No Starch Press was a repeat victim of this, and I have heard of other cases, too.

Third-party sellers flogging used books as new

As mentioned earlier, I do have issues with other sellers listing used items as new. They are almost always third-party sellers concentrating on the book market, and offer the books as “new” with amazingly low prices to win the buy box or push my listing out of it. They have not purchased the book new through wholesale channels in which I operate (such as Baker & Taylor or Ingram), because the discount is below my wholesale prices — in some cases, below the cost of printing and shipping the book from the printer!

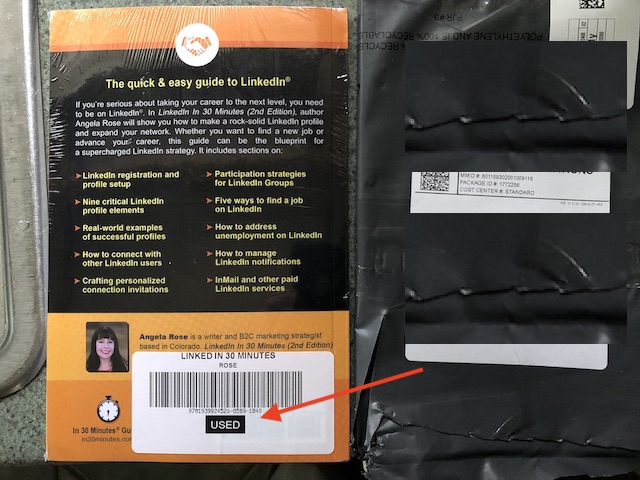

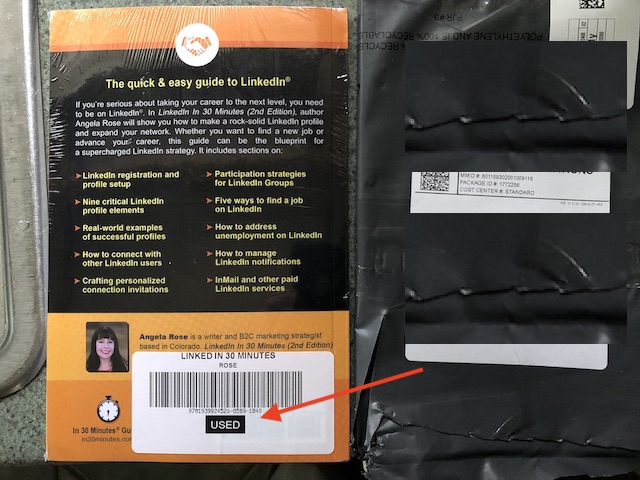

In all cases in which I have ordered one of these “new” books to determine the source, they have turned out to be used. This seller even sent a copy of our shrink-wrapped book about LinkedIn with a USED sticker on it:

This book was sold as “new” on Amazon, winning the buy box, yet was a used copy by the seller’s own admission!

Third-party book sellers playing games with shipping prices

Here’s another trick third-party sellers use to take publishers out of the buy box: Offering a new book for a ridiculously low price and then charging a ridiculously high shipping fee.

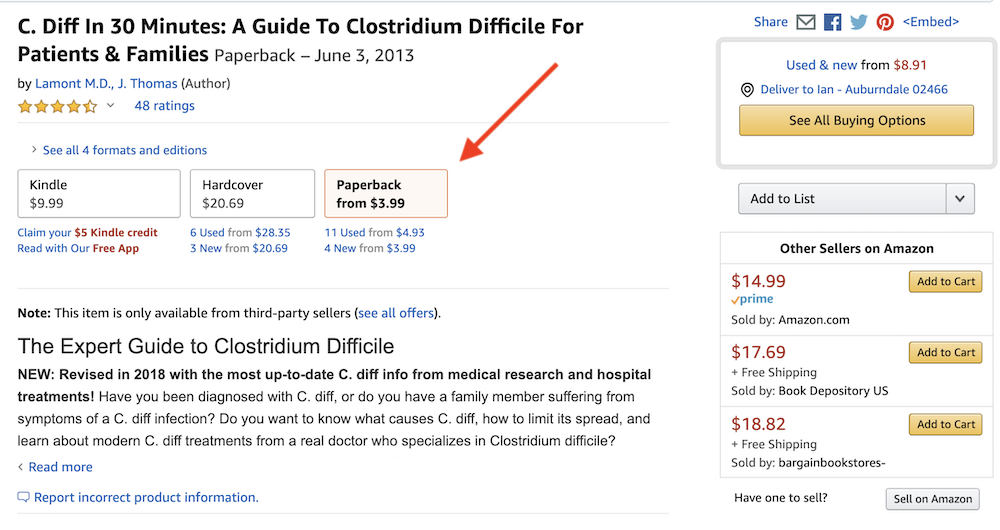

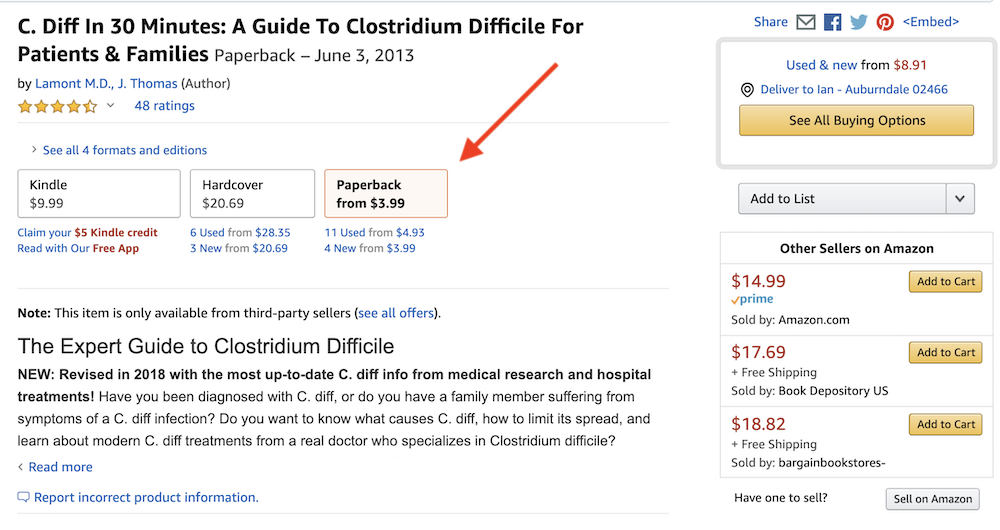

Check out the example below for C. Diff In 30 Minutes. The paperback retails for $14.99, but my listing is no longer am shown in the buy box because a third-party seller from Missouri is offering the book for $3.99. Sounds like a great deal, right?

But clicking “4 new from $3.99” takes people to a page that shows the seller charging an additional $27.99 for non-expedited shipping from Missouri to the Boston area, even though USPS Media Mail costs $2.75 for book that size, USPS First Class around $5, and a two-day Priority Mail flat-rate envelope $7.95.

But clicking “4 new from $3.99” takes people to a page that shows the seller charging an additional $27.99 for non-expedited shipping from Missouri to the Boston area, even though USPS Media Mail costs $2.75 for book that size, USPS First Class around $5, and a two-day Priority Mail flat-rate envelope $7.95.

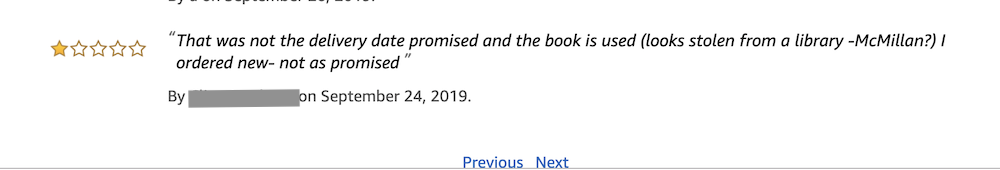

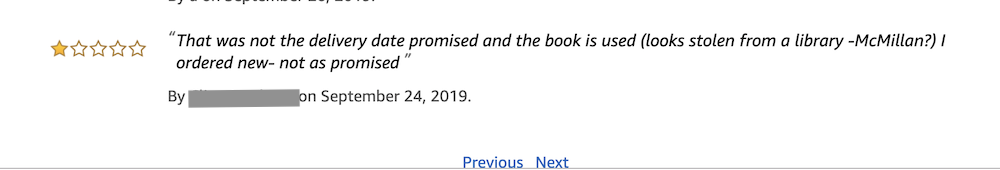

It’s also not clear if the book being sold is actually new. At least one customer of the third-party seller reported that a book sold as new was actually used and “looks stolen”:

It’s also not clear if the book being sold is actually new. At least one customer of the third-party seller reported that a book sold as new was actually used and “looks stolen”:

When I notified Amazon of this problem, they restored my publisher’s listing to the Buy Box … but the “3.99” version is still listed for sale, even though the actual cost to the customer is more than $30.

Used sales are an important option

Don’t get me wrong — it’s fine for sellers who resell used copies listed as used for a profit, and think it’s a good option for students and others who can’t afford a new copy. I also have no issue with a customer or library which received a copy of one our new books not wanting or needing it, and turning around to sell it as new (or returning it).

That said, every time a third-party seller lists a used book as new on Amazon and underprices the publisher, it’s taking money that the real publisher would otherwise get from the sale of an actual new book. It deceives buyers, and it cheats authors and publishers out of revenue and royalties.

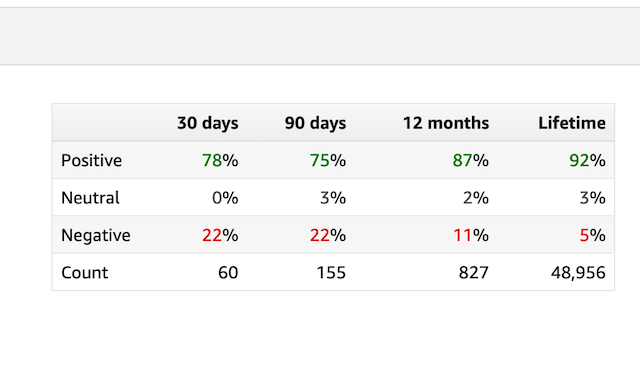

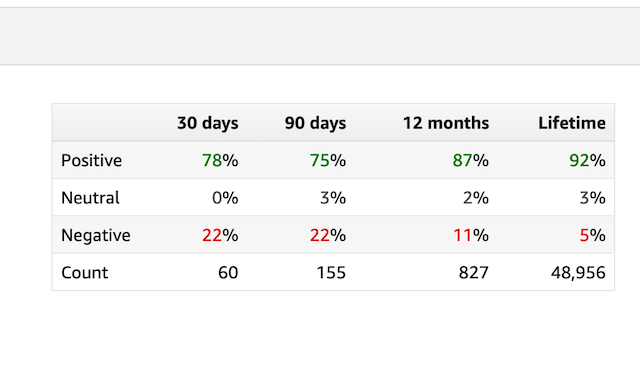

What they are doing violates Amazon TOS, too. Despite repeatedly reporting the bogus “new” cases to Amazon, I have not received any indication that Amazon took any action. The seller of the shrink-wrapped example with the “USED” sticker mentioned earlier is still selling books as a third party seller, and has lots of negative reviews:

After observing the mess caused by the Buy Box policy, and the apparent inaction on the part of Amazon to proactively stop the cheaters or punish wrongdoers, it’s clear that publishers are on the losing end of this fight. Pirates and sellers know it, too. Amazon’s message to them:

Win the buy box however you can. We don’t care if the original publisher/creator gets nothing. We won’t police your listings. We probably won’t punish you if you get caught, or we will only give you a light slap on the wrist. Even if many of Amazon’s customers are complaining, you can still stay in business on Amazon.

In terms of sellers of other types of goods winning or losing the buy box, Amazon makes available special services to brand owners (trademark owners with items in the Amazon Brand Registry) to fight counterfeits, including expedited take-down requests and access to paid services such as Amazon Transparency. The number-one point on the Amazon Transparency “learn more” page is “Proactive counterfeit protection.”

Sounds great in theory, but brands have to pay for it! For me, it works out to about 15 cents per item to use this service, not including additional manufacturing and design fees.

In other words, I’m paying for Amazon’s failure to police their own marketplace and prevent pirates and cheats. I’ve told them I won’t be proactively signing up brand SKUs for this service unless Amazon greatly reduces or eliminates the cost.

What has your experience been with Amazon counterfeit books or other goods?

A recent viewer of one of my passive income videos reached out to tell me she was at her wit’s end. In her 50s, she was tired of her career and was hoping passive income streams could lead to real income to support her financially. It had dawned on her that the get-rich-quick Amazon schemes, whether using Amazon KDP, Audible, or Amazon FBA were the modern equivalent of fool’s gold. What were her options?

A recent viewer of one of my passive income videos reached out to tell me she was at her wit’s end. In her 50s, she was tired of her career and was hoping passive income streams could lead to real income to support her financially. It had dawned on her that the get-rich-quick Amazon schemes, whether using Amazon KDP, Audible, or Amazon FBA were the modern equivalent of fool’s gold. What were her options?