An Introduction To My Portfolio

ø

Why take a cultural studies approach?

Religions are often perceived as homogenous monoliths. It is not uncommon to hear people ascribe certain beliefs or attitudes to an entire religious group, as if every single individual in that group worships in the exact same way. Islam, in particular, has often been misunderstood among the American public. “Muslims want to wage jihad against America.” “Islam oppresses women.” “Muslims want to impose shari’a law in the US.” Such statements are troublingly widespread in post-9/11 America, and they indicate a lack of knowledge about the diversity found in the Islamic faith. Terms like Islam and Muslims are tossed about like they have a single meaning, like there is an entity called Islam that programs all Muslims to practice their religion in the same way. In reality, Islam, like any religion, is embedded in the culture of the practitioner, and therefore the shape the religion takes varies based on the environment the practitioner inhabits. Thus, all Muslims construct their own interpretations of Islam.

Who is a Muslim?

The question about what defines a Muslim seems simple in theory, but answers to this question vary based on the cultural context of the individual asked. The word Muslim comes from the Arabic root for the word ‘submit.’ Therefore, ‘Muslim’ fundamentally means one who submits to God. An inclusive definition of “Muslim” (i.e. “muslim”) can theoretically encompass individuals from many religions, so long as they submit to God. In contrast, an exclusive definition of “Muslim” refers more specifically to submitters that consider themselves followers of the Islamic faith. Traditionally, this necessitates recitation of the shahada, or bearing witness that there is no God but Allah and that Muhammad is the messenger of God. The second part of the shahada, which asserts the importance of Muhammad, and differentiates Islam from other religious traditions, was actually added later. Furthermore, Shi’a Muslims include an additional line in their shahada, which states that Ali is the viceregent of God. This only demonstrates how definitions of what it means to be a Muslim varies widely. This diversity is a theme that we have encountered throughout the course, and therefore it has been captured in a number of pieces in my portfolio.

As Professor Asani points out in Infidels of Love, many Muslims consider love for God to be a defining characteristic for a Muslim. One example of a Muslim who believes in this interpretation of Islam quite fervently is Rabia al-Basri. Rabia al-Basri was a Sufi saint who was concerned that Muslims were worshipping out of a desire for heaven or a fear of hell, rather than a genuine love of God. It was said that she would run through the streets of Basra at night carrying a bucket of water in one hand and a lit torch in the other to put out the fires of hell and incinerate the gardens of heaven. By destroying these distractions, she would allow Muslims to return their focus to the only thing that actually matters: a love of God. I was particularly struck by this scene and chose to depict it in my watercolor painting “Rabia Barsi.” A serene Rabia is surrounded by billowing smoke, which arises from the burning gardens of heaven and the dying fires of hell. Despite the destruction occurring around her, a golden light surrounds Rabia. Furthermore, in the painting, I sought to replicate the style of stained glass, a form of art that relies heavily on light. I made these artistic choices so that Rabia would appear as if she were utterly bathed in light, a common symbol for God in Islamic art. It seemed fitting to me that a woman who felt so much love for God would be surrounded by and suffused in His light.

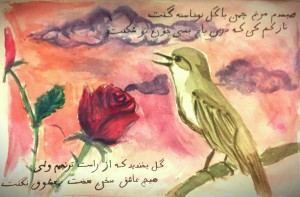

The importance of love of God in the lives of Muslims is also visible in Islamic poetry. The ghazal is a popular form of poetry that often takes the form of a love poem featuring a besotted lover lamenting about an unrequited love. These poems are often interpreted to be about the relationship between a Muslim and God. They depict this love to be consuming and intoxicating, and often draw on natural imagery and wine imagery. What is particularly interesting about these poems is that they can be read with a literal interpretation, as well as a spiritual one. In other words, the poems can be read simply as love poems without a religious connotation. However, those familiar with the symbols and themes used in ghazals can impose a religion interpretation to the texts. In addition to being a literary art, these poems were also often illustrated. I chose to follow this tradition and illustrate the following couplets from a ghazal by Hafiz:

At dawn the nightingale spoke to the newly-risen rose:

“Don’t put on airs, for many like you have opened in this garden.”

The rose laughed, “The truth does not offend, but never

Has a lover spoken harshly to his love.”

While most ghazals do not feature enjambment, these couplets are meant to be read together. I used watercolors to paint a literal illustration of this scene; my painting depicts a rose and a nightingale with a bright, sunrise in the background. The original Persian texts adorns the painting as well. Because the nightingale often represents the lover while the rose represents the beloved, I interpreted the lines to mean that if someone loves God, as they should, then they would not speak critically to Him. In another interpretation, the rose and nightingale can be seen as representative of earthly love; however because the nightingale is harsh to his beloved, contrary to the true nature of love, this sort of earthly love is false. Only love for God is real.

The importance of love in defining a Muslim is not only limited to personal or artistic definitions of the word; interpretations of religious texts also emphasize the key role love plays in the life of a Muslim. One well-known story about the Prophet relates his isra (night journey) and mi’raj (ascension) into heaven. According to this tale, the angel Gabriel awoke the Prophet in the middle of the night, and he was taken on a journey on the back of a mystical creature called Buraq, to what was the farthest mosque at the time, the Masjid Al-Aqsa in Jerusalem. After praying there, the Prophet traveled to the different levels of Heaven on the Buraq’s back, where he met various prophets, and finally God himself. While the angel Gabriel was able to accompany the Prophet through all other legs of his journey, he could not accompany him as he witnessed God; only Buraq could bring him there. Although some interpret the isra and mi’raj as a literal journey, others interpret it as a metaphor for the journey to truly knowing God. In the latter interpretation, Buraq represents love for God and the angel Gabriel represents the intellect. Thus, the intellect has no place in this voyage to truly know God; one simply needs love. Intrigued by the multifaceted nature of this story, I wanted to create a model of Buraq, a representation of love itself. In my model, there is a lantern placed over Buraq’s heart. The light symbolizes both God himself and the Prophet Muhammad, who is described as a lamp that brings the light of God to the people. The placement of the light is intentional; its location over Buraq’s heart stands for the love of God and the Prophet. Narratives such as this further reveal the essential role that love plays in the identity of a Muslim.

As seen in the example above, Muslims can be defined not only by their love for God; this love also extends to the Prophet Muhammad. For many Muslims, the Prophet is an example of the ideal human, and they seek to emulate his life. Many South Asian poems are written from the point-of-view of a young woman waiting for her bridegroom, who represents the Prophet Muhammad. In this way, these poets use romantic love, which many of their readers have experienced themselves, to represent a more spiritual love for the Prophet. I chose to attempt to write my own poem in the South Asian style; like ghazals these poems can be read as love poems, but they are also imbued with religious symbolism. On the surface, “I lie in wait, love” is about a young lover, who aches to be reunited with her bridegroom. The pain she feels is meant to echo the pain Muslims experience as a result of separation from the Prophet and his message. Even as she suffers in the burning desert, an allusion to the fires of Hell, she dreams of her future with her beloved in his lush gardens, an allusion to the gardens of Paradise. Her love is a loyal love; she refuses to be swayed by the wealthy suitors who court her; these suitors are meant to represent other faiths that Muslims encounter in their daily lives; although these other religions may have tempting promises, they are ultimately lacking because of the pure love Muslims have for the Islamic faith. Thus, love is a theme prevalent in Islamic art because for many Muslims love is a defining aspect of their faith and identity.

For some Muslims, God is more than a figure that they love dearly; instead, they view themselves as reflections of God. For example, Al-Ghazali, a notable Islamic scholar, writes, “The universe is the mirror of God and the heart of man is the mirror of the universe. The human soul is the masterpiece of creation, and the whole material world is placed under its control. If you then would know God, you must look into your own heart.” Many Sufis seek to become less egocentric so that they can experience God; this is compared to polishing the mirror of the heart so that they can reflect the attributes of God. This is an idea that is also found in Attar’s The Conference of the Birds, which tells the tale of a group of birds that undertake a perilous journey to find their king Simorgh. At the end of the voyage, only thirty birds remain. However, instead of finding a king, they find their own reflection; the Simorgh had been within them the entire time. This idea is also reflected in Attar’s choice of name for the mythical bird-king. Simorgh is a pun of the Persian phrase si morgh, which translates to thirty birds.

I wanted to capture the concept of Muslims as reflections of God that was presented in The Conference of the Birds. I created a tessellation of birds and juxtaposed it with a reflection of that image. I chose to depict the birds in the form of a tessellation because the pattern can extend infinitely in all directions. The concept of infinity is meant to evoke the eternal nature of God. I wanted to place the image next to its own reflection to represent how God is within everyone, i.e. that people are reflections of God. Muslims that follow the right path are able to access this intimate divine-human connection, and experience God for themselves.

While some define Muslims through specific characteristics like love, compassion, and charity, others define Islam using negative definitions, i.e. by designating what Islam is not. These negative definitions of Islam are especially prevalent among ‘extremists’ Islamic groups like the Taliban. These groups interpret Islam to be the antithesis of Western culture; therefore for them, an ideal Muslim is one that is fundamentally un-Western. For this reason, actions such as growing a thick beard or wearing a niqab are particularly important; they draw a visible contrast between their society and Western societies, and they can be interpreted as a reaction to the perceived disintegrating morals in Western societies.

The Iranian government as depicted in Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis also appears to rely heavily on this negative definition of Islam. While reading the graphic novel, I was particularly struck by how seeming innocuous acts like having a party, spending time with a member of the opposite sex, or listening to popular music could be considered punishable actions. Many of these acts are not explicitly forbidden in the Qu’ran itself; rather the perceived harmfulness of these acts is a direct result of their permissibility in American culture. It is not uncommon for governments, especially new and authoritarian governments, to resort to propaganda in order to persuade citizens that the way of life they advocate is the only proper way to live life. In Persepolis, the children in school are required to perform rituals in honor of the men, who died in war; Marjane reflects on the absurdity of the self-flagellation in which the citizen of Iran participate. Similarly, as she grows older, Marjane becomes acutely aware of the propaganda that is aired on the news.

After learning about the actions of the Iranian government, I wanted to produce a piece of propaganda that reflected their bias against Western culture and their negative definition of Islam. I created a simple graphic that features a fire with an American flag planted in it. It symbolizes how Hell is a land that belongs to America; in order to avoid this grim fate, one needs to treat everything American as anathema. Consequently, above the image is a simple set of instructions: “Don’t be like the Americans.” I used a very minimalist design to emphasize how this belief was the core characteristic of this government’s interpretation of Islam.

As reflected in a number of pieces in my portfolio, a Muslim can be defined in numerous ways. Ones definition of what it means to be a Muslim is highly dependent on ones cultural background. For some, being a Muslim simply means submitting to God. For others, it requires belief in a number of core tenets of the Islamic faith, such as recitation of the shahada, prayer, and charity. Some people consider love for God and the Prophet Muhammad to be a fundamental feature of being a Muslim. Others believe humans are reflections of God Himself, and that Muslims are able to access this connection. For some, it is more important that a Muslim distinguishes himself or herself from non-Muslim cultures, especially from decadent Western cultures. This diversity in these definitions emphasizes how flawed it is for someone to make generalized statements about all Muslims.

What is the role of art in religion?

By taking a cultural studies approach to studying Islam, it becomes clear that art is a vital channel through which Muslims can express their faith. Fundamentally, art allows people to express their emotions; it is a means, through which they can lament their hardships and celebrate their triumphs, delve into questions about their existence and reflect on the mundane events in their lives. Similarly, religion is a way to understand the universe and one’s role in it. In many ways art complements religion. For artists that consider their religion to be a key aspect of their identity, it makes sense that they use their art to practice their faith. Indeed, art is a way for people to explore the nature of their own beliefs, to express their love for God, to explain their conception of how the world works, or to teach others about their faith. Although many may not associate art and religion, in reality, a study of a religion that does not also consider the art of that faith neglects a significant piece of how people actually engage with the religion itself.