Flash back to 2006. Professor Marcia Inhorn, a medical anthropologist and director of the Center for Middle Eastern and North African Studies at the University of Michigan, is invited to lecture in Tehran on her field of expertise, infertility and assisted reproductive technologies in Muslim countries. On her return, she seeks to dispel misconceptions about the Middle East. Because of the “American daily diet of fearsome media discourses about the Middle East, particularly Iran,” she complains, “it was difficult to convince relatives, including my 80-year-old mother, that it was safe for me, a mother of two young children, to travel to that part of the world.” Landing in Detroit, she finds the same bias:

Flash back to 2006. Professor Marcia Inhorn, a medical anthropologist and director of the Center for Middle Eastern and North African Studies at the University of Michigan, is invited to lecture in Tehran on her field of expertise, infertility and assisted reproductive technologies in Muslim countries. On her return, she seeks to dispel misconceptions about the Middle East. Because of the “American daily diet of fearsome media discourses about the Middle East, particularly Iran,” she complains, “it was difficult to convince relatives, including my 80-year-old mother, that it was safe for me, a mother of two young children, to travel to that part of the world.” Landing in Detroit, she finds the same bias:

When the customs official at the Detroit International Airport asked me why I had been “over there,” I told him it was for an academic conference. Then he asked, “And they didn’t behead you?,” to which I replied, “No, they served me delicious food.” He retorted, “But you never know what was in it (i.e., the food),” to which I responded, perhaps too flippantly, “Probably uranium.” Fortunately, he returned my passport and let me proceed to baggage claim, where I retrieved my two gorgeous Persian carpets.

Inhorn’s conclusion:

I would argue that such fear-mongering is very unwise. It is leading to closed minds, closed embassies, restricted visas, travel bans and demeaning airport luggage searches for those of us who overcome these travel restrictions.

They’re not going to cut off our heads or irradiate us—that’s her message. They just want to serve us their delicious food and sell us their gorgeous carpets. Nothing to fear but fear itself.

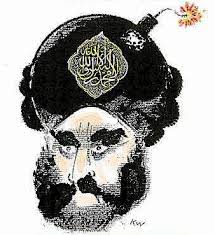

Flash forward to July 2009. Professor Inhorn has recently made a big move: she’s now at Yale, where she chairs its Middle East center (known as the Council on Middle East Studies). She’s seated in a cafe in Boston with Jytte Klausen, author of a forthcoming book on the Danish cartoons affair—those dozen cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad that Muslim extremists seized upon in 2005. (Also around the table: the director of Yale University Press—the book’s publisher—and a vice president of Yale.) Professor Inhorn has been called in by the publisher to break some bad news to the author. Here’s a summary of what transpired at that meeting (as told by Klausen to Roger Kimball):

Their two-hour cup of coffee on July 23rd was not a pleasant occasion…. Unfortunately, [Klausen’s] book about the Danish cartoons could only be published without the cartoons. Moreover, Professor Inhorn told her, that depiction of Mohammed in hell by Doré would have to go. How about the less graphic image of Mohammed by Dalí? she suggested.

Nope. No-go on that either. In fact, Yale was embarking a new regime of iconoclasm: no representations of that 7th-century religious figure were allowed.

The reason? Yale University Press, relying on Professor Inhorn and other “expert” consultants, had determined that running the cartoons “ran a serious risk of instigating violence,” and that “publishing other illustrations of the Prophet Muhammad in the context of this book about the Danish cartoon controversy raised similar risk.” A statement by Yale University Press justifying its decision directly quoted Inhorn: “If Yale publishes this book with any of the proposed illustrations, it is likely to provoke a violent outcry.”

Wait a minute…. The last time we encountered Professor Inhorn, she was telling us to ignore the fear-mongering, not to let the media dupe us into expecting the worst. Now, behind the scenes, she’s telling an expert author, who knows a lot more about the topic than she does, that Yale’s press absolutely must expect the worst. The author’s book must be censored.

So let me try to reconcile Professor Inhorn’s view of how it works “over there.” Sure, they’ll feed you delicious food and sell you gorgeous carpets, but they can suddenly be “instigated” to violence by the mere reproduction, in a scholarly book, not only of old cartoons that anyone can access in a flash on the internet, but canonical works of Western art that have been in the public domain for decades (and even representations of the Prophet Muhammad in Islamic art). How easily they come unhinged! Why, show them the wrong image, and they could… well, behead you, just like that. And Professor Inhorn fancies herself above the “fearsome media discourses about the Middle East”….

Now I don’t know if publishing these images in an academic book at this time would run a “serious risk of instigating violence.” Everything I do know tells me that it wouldn’t. Extremists are always looking for something to exploit, but it has to be a new, unprecedented (perceived) offense against Islam. Dante’s Inferno, Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses, the Danish cartoons—these are all old perceived offenses, too familiar to fire up a sense of indignation. No doubt there will be another round at some point—and no doubt, its ostensible “cause” will surprise us all. (That’s because it won’t really be the cause, but a pretext—like the Danish cartoons.)

But that’s neither here nor there. The reason we have “restricted visas, travel bans and demeaning airport luggage searches” (and other disdained measures) is so that in America, a university press can publish the Danish cartoons in a book about the Danish cartoons, and do so without fear. If we didn’t have that line of defense, we would constantly have to censor ourselves and ban whole classes of free expression, lest we be tormented by fanatic extremists.

Given a choice between undergoing a baggage search and muzzling themselves, Americans prefer the former. More than that: if you threaten their freedoms, they may just cross an ocean to search for you. That’s why America is free and a refuge for the world. What sort of American would prefer the muzzle? Now we know.

Update, August 19: Here are more details about that outrageous baggage inspection:

Changing planes in Paris on her way home [from Iran], Inhorn was pulled aside and required to provide proof that her business in Iran had been strictly academic. Security workers slapped a high-risk stamp on her carry-on bags, then donned latex gloves to manually inspect every item. “It was very demeaning, simply because I had been in Iran,” Inhorn says. “So that’s the particular political moment I was in.”

It sounds entirely routine, and speaks less about the “political moment” than about Inhorn’s sense of entitlement.

Pointers: Read Christopher Hitchens, “Yale Surrenders,” and the statement by the American Association of University Professors, “Academic Freedom Abridged at Yale Press.”