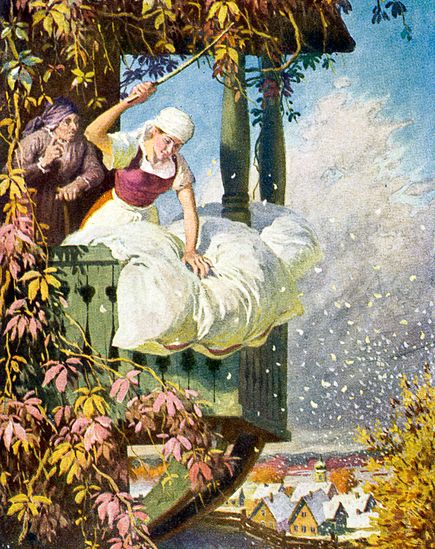

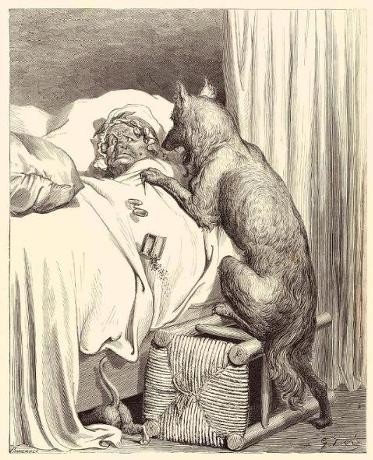

We all know about that terrible Monster Book of Monsters in Harry Potter, but how many other literary books have magical properties? Walter Benjamin tells us about one of those magical books in a short story by Hans Christian Andersen:

“In one of Andersen’s tales, there is a picture-book that cost ‘half a kingdom.’ In it everything was alive. ‘The birds sang, and people cam out of the book and spoke.’ But when the princess turned the page, “they leaped back in again so that there should be no disorder.’ Pretty and unfocused, like so much that Andersen wrote, this little invention misses the point by a hair’s breadth. Things do not come out to meet the picturing child from the pages of the book; instead, in looking, the child enters into them as a cloud that becomes suffused with the riotous colors of the world of pictures.”

There is also Lucy’s book in the Chronicles of Narnia–that intoxicating story in the Magician’s Book that she forgets as soon as she turns the pages–and she can’t go back! Any others? Inkheart?