Walter Dean Myers writes:

But there was something missing. I needed more than the characters in the Bible to identify with, or even the characters in Arthur Miller’s plays or my beloved Balzac. As I discovered who I was, a black teenager in a white-dominated world, I saw that these characters, these lives, were not mine. I didn’t want to become the “black” representative, or some shining example of diversity. What I wanted, needed really, was to become an integral and valued part of the mosaic that I saw around me.

Books did not become my enemies. They were more like friends with whom I no longer felt comfortable. I stopped reading. I stopped going to school. On my 17th birthday, I joined the Army. In retrospect I see that I had lost the potential person I would become — an odd idea that I could not have articulated at the time, but that seems so clear today.

My post-Army days became dreadful, a drunken stumble through life, with me holding on just enough to survive. Fueled by the shortest and most meaningful conversation I had ever had in a school hallway, with the one English teacher in my high school, Stuyvesant, who knew I was going to drop out, I began to write short columns for a local tabloid, and racy stories for men’s magazines. Seeing my name in print helped. A little.

Then I read a story by James Baldwin: “Sonny’s Blues.” I didn’t love the story, but I was lifted by it, for it took place in Harlem, and it was a story concerned with black people like those I knew. By humanizing the people who were like me, Baldwin’s story also humanized me. The story gave me a permission that I didn’t know I needed, the permission to write about my own landscape, my own map.

During my only meeting with Baldwin, at City College, I blurted out to him what his story had done for me. “I know exactly what you mean,” he said. “I had to leave Harlem and the United States to search for who I was. Isn’t that a shame?”

When I left Baldwin that day I felt elated that I had met a writer I had so admired, and that we had had a shared experience. But later I realized how much more meaningful it would have been to have known Baldwin’s story at 15, or at 14. Perhaps even younger, before I had started my subconscious quest for identity.

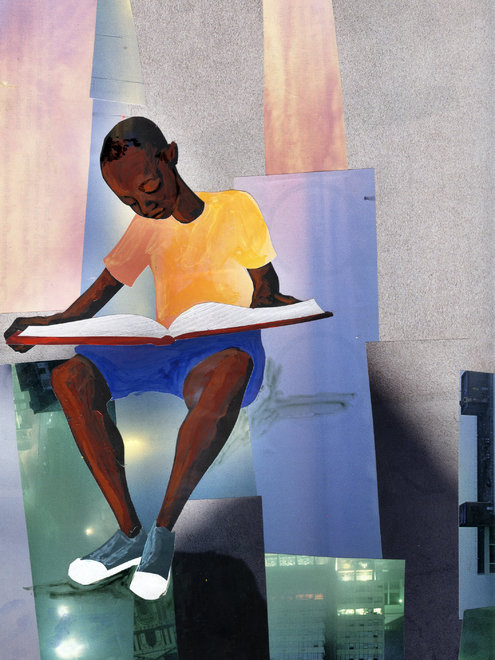

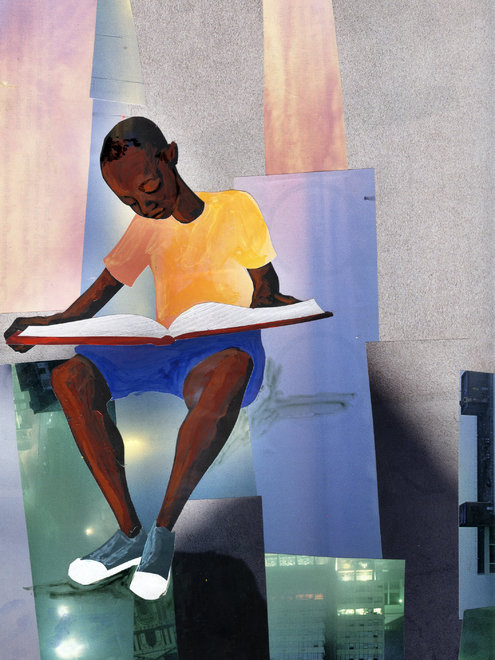

And here’s Christopher Myers:

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/16/opinion/sunday/the-apartheid-of-childrens-literature.html?action=click&contentCollection=Opinion®ion=Footer&module=MoreInSection&pgtype=article

Of 3,200 children’s books published in 2013, just 93 were about black people, according to a study by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center at the University of Wisconsin.

Add this event to your calendar

Add this event to your calendar