I discussed youths’ social media engagement within the Japanese context at IAMCR in Dublin, 20131. In my presentation, by using the concepts of high and low context cultures, I demonstrated the reason why Japanese young people are using both American and Japanese sites.

IAMCR 2013 Conference Dublin, 25-29 June 2013

Social Media in Japan

When I interviewed Japanese young people in 2009, they were mainly using Japanese sites Mixi. However when I did the same in 2012, ‘Mixi fatigue’ had set in and most were communicating through American sites like Facebook and Twitter, as well as a new Japanese site, Line. Facebook has become popular since the movie, “the social network” had been released on January 15, 2011 in Japan. Line was launched in 2011 by NHN Japan and has become the most popular social media in Japan. But why are they using both American and Japanese sites?

High and Low Context Cultures

A possible answer may lie in an old concept first proposed by cultural anthropologist Edward T Hall (1976) – the concepts of high and low context cultures. This work is still influential in the field of intercultural communication studies, social linguistics and business. In communication studies, Steinfatt (2009, pp. 278-279) introduces this binary concept as follows:

In a high-context culture, the significance intended by a message is located largely in the situation; the relationships of the communicators; and their beliefs, values, and cultural norm prescriptions…. High-context cultures usually emphasize politeness, nonverbal communication, and indirect phrasings, rather than frankness and directness, in order to avoid hurt feelings. They emphasize the group over the individuals and tend to encourage in-groups and group reliance…

In a low-context culture, the meanings intended by a message are located in the interpretations of its words and their arrangement. These are carefully selected in an attempt to express those meanings clearly and explicitly… Low-context cultures often place a high value on the individual, encouraging self-reliance.

Within this framework, the United States may be understood as a low context culture while Japan may be seen as a high context culture. Bearing in mind that these concepts were developed in a pre-internet age, I examined and recontextualised them in the current era, in relation to the advent of social media.

Twitter in Japan as a high context culture

Arguably, the US-based microblogging service, Twitter, is a good example of a communication pattern arising from a low context culture. Communication is done in 140 characters or less. Kimura (2012) suggests that the reason for the recent popularity of Twitter in Japan is that there is no obligation to reply immediately, unlike the case with Mixi and emails via mobile phones.

One of my informants, Hiro, a twenty one year-old male college student, has over 1000 followers on Twitter and constantly interacts with others. However, his Twitter account sometimes experiences enjo (becoming flooded by comments), especially when he gets criticized. He told me, ‘I can’t explain the context within 140 characters’. On Twitter, where one can only write the content with very little or no context, some users who do not share their interlocutor’s context might interpret posts wrongly. Others might get upset by the perceived rudeness in writing style.

It is true that the internet enables us to communicate with others directly beyond differences of age, gender and status. However, once people communicate with others using their real identity on the internet, the same social norms that exist in face-to-face communication in Japan, as a high context culture, can become reinforced in mediated online communication.

Some young Twitter users believe that only their close friends, who “follow” them, can read their tweets. They often forget that their comments are accessible to all on the site. They thus write their opinions frankly and directly, as if they were within a small closed uchi, (uchi means inside or intimate circle of friends).

Some Twitter users have become more conscious that their posts may also be read by people in their soto (soto means outside) who may suddenly “intrude” and destroy any illusion that they were communicating in an extended uchi.

On the other hand, Line enables its users to create different groups and keep constant intra-group communication within each closed space. There, they feel secure. Opinions, beliefs, values and cultural norms are presumably shared. Unlike in the open social media such as Twitter, here, the users are shielded from their soto, the outside.

Line and uchi creation/ re-creation

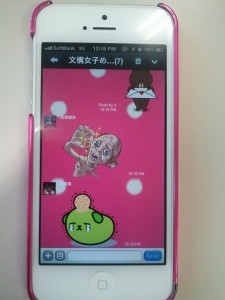

There are three main reasons for Line’s current popularity among young people in Japan: it is free of charge, it operates as a closed space, and it enables the sharing of emotions by the use of ‘stickers’. I will show you an example how Mika, a 19 year-old female college student, communicates with ‘stickers’.

Risa sent a message saying simply ‘Noisy!’ because her group was exchanging messages constantly and this meant her mobile phone kept vibrating during class. This wasn’t meant to signal that she was actually angry though. The other members responded immediately at 12:16 pm, and Mika then sent the message, ‘Sorry, sorry’, followed by:

Mika: (Mika sends a bear sticker – the bear is holding a letter to show her love – thus indicating that she is asking Risa to forgive her.)

Risa: (Risa sends a sticker of Gollum from Lord of the Rings to tell her ‘OK’. The Gollum’s gesture of holding the ring is similar to the OK sign in Japan.)

Moe: (Moe sends a Mameshiba sticker – the image shows a figure with an injured head who is crying. This shows that Risa’s message had hurt Mika and that she feels sad and sorry.)

Line facilitates patterns of constant communication by showing the time at which each member reads their messages, thus providing pressure for an immediate response, in much the same way that Mixi does. In this way, traditional Japanese social norms continue to be reinforced by ‘emotional bonds’ and ‘constant communication’. Some of my informants have already expressed ‘Line fatigue’.

Even so, through negotiating the interpretation of Western and Japanese consumer cultural products among uchi members, these Japanese young people share their own cultural values and reinforce their social intimacy and emotional bonds, and thus they reflexively create and recreate multiple uchi on Line.

Notes

Takahashi, T. “Japanese Youth and Social Media”. 2013 Conference of the International Association for Media and Communication Research (IAMCR), Dublin, Ireland, June 2013.

References

Hall, E. T. (1976) Beyond Culture. New York: Anchor books.

Kimura, T. (2012) Dejitaru neitebu no jidai [The age of digital natives]. Tokyo: Heibonshinsho.

Steinfatt T. M. (2009) ‘High-context and low-context communication’ in S. W. Littlejohn and K. Foss (eds) Encyclopedia of Communication Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, pp. 278-279.

Takahashi, T (forthcoming) Youth, Social Media and Connectivity in Japan. In Seargeant, P. and C. Tagg (eds) “The Language of Social Media: Community and Identity on the Internet”. Palgrave.