We

We think of markets as competitive places: arenas, battlegrounds, playing fields, boxing rings. Which they are, if you look at them from the standpoint of vendors. As buyers, we do want vendors to compete, of course. But we also want them to cooperate — with us. From our perspective, markets are places where we shop, meet and do business. We want the freedom to do that, and we don’t want sellers taking any of that away, even if they think doing that makes them better competitors.

think of markets as competitive places: arenas, battlegrounds, playing fields, boxing rings. Which they are, if you look at them from the standpoint of vendors. As buyers, we do want vendors to compete, of course. But we also want them to cooperate — with us. From our perspective, markets are places where we shop, meet and do business. We want the freedom to do that, and we don’t want sellers taking any of that away, even if they think doing that makes them better competitors.

For decades, if not for a century or more, taking customers’ freedoms away has been something of a virtue for vendors. It’s not for nothing that marketers talk about “acquiring,” “capturing,” “owning” and “managing” customers as if they were slaves or cattle. In the old industrial economy, this made sense. It was easier to serve managed customers than free ones. You could limit the variables you addressed. Even today we sometimes like having our choices restricted, and gladly make the Faustian bargain of captivity. But even here we see the downsides, which go beyond lack of choice. Being captive may seem safe in some ways, but it also makes us vulnerable to a single source of goods on which we have no choice but to depend.

On the sell side, there are two problems. One is the burden of management itself, which should be easier if customers were also carrying some of the load. The other is intelligence. When all you know is what you learn from your captive customers (say, through your loyalty program), you don’t know enough. There is far more happening in the marketplace than you can learn and crunch only in your own exclusive ways.

What we need now is for vendors to discover that free customers are more valuable than captive ones. For that we need to equip customers with better ways to enjoy and express their freedom, including ways of engaging that work consistently for many vendors, rather than in as many different ways ways as there are vendors — which is the “system” (that isn’t) we have now.

There are lots of VRM development efforts working on both the customer and vendor sides of this challenge. In this post I want to draw attention to the symbols that represent those two sides, which we call r-buttons, two of which appear above. Yours is the left one. The vendor’s is the right one. They face each other like magnets, and are open on the facing ends.

These are designed to support what Steve Gillmor calls gestures, which he started talking about back in 2005 or so. I paid some respect to gestures (though I didn’t yet understand what he meant) in The Intention Economy, a piece I wrote for Linux Journal in 2006. (That same title is also the one for book I’m writing for Harvard Business Press. The subtitle is What happens when customers get real power.) On the sell side, in a browser environment, the vendor puts some RDFa in its HTML that says “We welcome free customers.” That can mean many things, but the most important is this: Free customers bring their own means of engagement. It also means they bring their own terms of engagement.

Being open to free customers doesn’t mean that a vendor has to accept the customer’s terms. It does mean that the vendor doesn’t believe it has to provide all those terms itself, through the currently defaulted contracts of adhesion that most of us click “accept” for, almost daily. We have those because from the dawn of e-commerce sellers have assumed that they alone have full responsibility for relationships with customers. Maybe now that dawn has passed, we can get some daylight on other ways of getting along in a free and open marketplace.

The gesture shown here —

— is the vendor (in this case the public radio station KQED, which I’m just using as an example here) expressing openness to the user, through that RDFa code in its HTML. Without that code, the right-side r-button would be gray. The red color on the left side shows that the user has his or her own code for engagement, ready to go. (I unpack some of this stuff here.)

Putting in that RDFa would be trivial for a CRM system. Or even for a CMS (content management system). Next step: (I have Craig Burton leading me on this… he’s on the phone with me right now…) RESTful APIs for customer data. Check slide 69 here. Also slides 98 and 99. And 122, 124, 133 and 153.

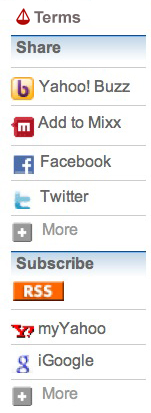

If I’m not mistaken, a little bit of RDFa can populate a pop-down menu on the site’s side that might look like this:

All the lower stuff is typical “here are our social links” jive. The important new one is that item at the top. It’s the new place for “legal” (the symbol is one side of a “scale of justice”) but it doesn’t say “these are our non-negotiable terms of service (or privacy policies, or other contracts of adhesion). Just by appearing there it says “We’re open to what you bring to the table. Click here to see how.” This in turn opens the door to a whole new way for buyers and sellers to relate: one that doesn’t need to start with the buyer (or the user) just “accepting” terms he or she doesn’t bother to read because they give all advantages to the seller and are not negotiable. Instead it is an open door like one in a store. Much can be implicit, casual and free of obligation. No new law is required here. Just new practice. This worked for Creative Commons (which neither offered nor required new copyright law), and it can work for r-commerce (a term I just made up). As with Creative Commons, what happens behind that symbol can be machine, lawyer or human-readable. You don’t have to click on it. If your policy as a buyer is that you don’t want to to be tracked by advertisers, you can specify that, and the site can hear and respond to it. The system is, as Renee Lloyd puts it, the difference between a handcuff and a handshake.

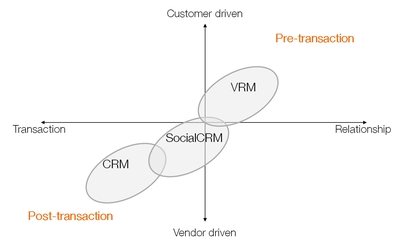

Giving customers means for showing up in the marketplace with their own terms of engagement is a core job right now for VRM. Being ready to deal with customers who bring their own terms is equally important for CRM. What I wrote here goes into some of the progress being made for both. Much more is going on as well. (I’m writing about this stuff because these are the development projects I’m involved with personally. There are many others.)

What I want to make clear here is that symbols are necessary. We need graphic representations of states and actions, and what’s possible for both. And we need ones that are not encumbered by anybody’s intellectual property claims. That’s why r-buttons are free for the using. Everybody is also free to use something else, if you think it’s better. I don’t care. I just know we need symbols, and these are some we’ve been using while we’ve been developing stuff.

In the next few weeks there will be a number of occasions for VRM and CRM folks to get together, to talk, to start building toward each other, and to start training company legal departments in the new ways of open markets — cooperative ways, rather than just coercive ones. Looking forward to seeing how that all goes.