The Television Cannot Be Revolutionized

April 12th, 2010 by Christian(or: Emerging Bottlenecks in Online Video?)

Here is the outline, notes, slides, audio, and video from my talk at Harvard last week (http://cyber.law.harvard.edu/events/ luncheon/2010/04/sandvig). David Weinberger also liveblogged my talk — thank you David for doing that! His liveblogging is here. @ninabeth tweeted my talk. Thank you Nina for doing that!

[Click to go to the audio/video archive page.

Notes and slides are below.]

The Television Cannot Be Revolutionized

Christian Sandvig

ABSTRACT

Video on the Internet briefly promised us a cultural future of decentralized production and daring changes in form–even beyond dancing kittens and laughing babies. Yet recent developments on sites like YouTube, Hulu, and Fancast as well as research about how audiences watch online video both suggest a retrenchment of structures from the old “mass media” system rather than anything daring. In this talk I’ll argue that choices about the distribution infrastructure for video will determine whether all our future screens will be the same.

****************************************

Talk Outline as Prepared [These are ROUGH speaker’s notes. You have been warned.]

This title is a response to Amanda Lotz’s excellent book The Television Will Be Revolutionized, which is a take off of Gil Scott Heron’s poem/song The Revolution Will Not Be Televised. My response to Lotz is that the Television cannot be revolutionized, as I’ll explain.

A summary of the entire argument: The “Mass” media are usually defined by a distribution bottleneck. I once thought that after the distribution bottleneck was removed by the Internet, television would change. It did so for a while, but now it looks like the mass media are retrenching. It may be that we didn’t understand the distribution bottleneck, or that there is a new one — and that there are other bottlenecks that strongly shape television and are just as important as distribution. In this talk I’ll lay out a set of concerns and ask you (in Q&A) if they have any merit and if so, how we should study them.

I. Introduction: Old vs. New

Molly Fitzsimmons produced an excellent documentary called “Puppy Love” that I strongly recommend. It’s about her father’s attempt to launch a new cable channel in 1995. His idea was a channel consisting entirely of puppies (and later, other young animals: kittens, ducklings, etc.). The documentary gives you an idea of what it took to start a new cable channel c. 1995. Even though his proposed channel had better test numbers than Court TV and TBS, industry giants Ted Turner, Barry Diller, and Rupert Murdoch declined to pursue his idea because it was “too weird.” Without their sponsorship he estimated that he needed to raise $17m to launch the channel himself. That’s the way we think about traditional television: as a distribution bottleneck. There are only a few channels and someone else gets to decide what we see.

But now things are different — it is 2010. There are all kinds of puppy channels and kitten channels online. You could say that YouTube is a giant kitten channel. It looks like anyone can put their videos online via YouTube and other sites, or possibly with their own Web server.

Yes online video was refreshingly (even bizarrely) different for a while, but over the last 12 months the signs are that online video is changing. It is starting to look more like the traditional mass media of old. How can we study and hopefully understand what is going on?

II. The Retrenchment

While I expected big changes in form and structure as video moved to the Internet, the older media formats seem to be retrenching. Examples of the retrenchment:

- YouTube Rentals Program

- YouTube Partnership Programs and Emphasis on Licensing Deals with Traditional Media Giants

- Expansion of Advertising on all Video Upload Sites

- YouTube Pursuing Licensing Deals to Stream Sporting Events

- YouTube UI Redesign — Meant to make it look more like traditional television according to company sources (“We want you to go into passive mode, sit back and watch.” –Margaret Stewart, Head of User Experience, YouTube)

- All Video Sites Incorporate Features to Reduce Interactivity (e.g., the continually streaming queue)

- Increased Popularity of Hulu (an outlet for traditional media companies)

- Other Ventures like Comcast Fancast (looks just like Hulu)

All this is nicely summarized by the quote: “The Internet, which was thought to be a TV killer, is turning out to be its wingman.” Brian Stelter, NYT

Another way to summarize it would be to say that the “new” video outlets are behaving more and more like old television networks.

So is the decline of television exaggerated?

Despite the bad name that traditional television has in some circles, it still dominates the media experience. Depending on which study you believe, the average American in 2009 spent between 5 and 6 hours per day watching television. While the decline of the mass television audience has gotten a lot of attention, some studies (Neilsen/Ball State Univ.) show that the television watching experience is shifting in character but that people are not necessarily watching less video. E.g., they may be multiscreening more, and watching more YouTube and Hulu — this accounts for the lost time that they used to spend with cable and broadcast TV.

The sources of novelty in online video distribution, chiefly YouTube, were under a great deal of public pressure last year. In 2009 YouTube and parent company Google were frequently warned by financial analysts to monetize their content more effectively. By one estimate YouTube was spending $1m/month in bandwidth in 2007, was losing $1.4-1.6m per day in 2009, and was spending more than $1 per unique visitor in 2009. Hulu, representing a more traditional take on online video (it only distributes established media properties from traditional media corporations) is profitable for the first time as of 2010.*

A lot of the pressure on YouTube emphasized that the amateur content is a liability — this is the main thing that distinguishes online video from traditional TV. It is “too weird.” (Remember that phrase?)

As Dan Schiller pointed out last year, it’s useful to keep in mind that popularity is no guarantee of success for a media outlet in an advertising-supported regime. Magazines like Look, Coronet, and LIFE Magazine were very popular as late as the 1970s. LIFE was pioneering a new format called photojournalism when it ceased publication as a weekly even as its circulation was increasing in late 1972. Although it ceased publication for many reasons, a significant one was that the audience it was attracting was not demographically appealing to advertisers.

So YouTube’s The Evolution of Dance, laughing babies, and kittens may indeed be popular but this is no guarantee of YouTube’s continued existence. In response, the new YouTube looks like old Television.

III. What kind of analysis do we need to understand what is going on?

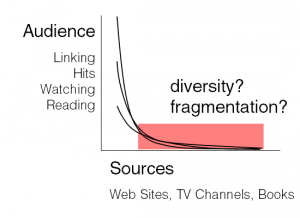

It has often been emphasized that the distribution of popularity for a variety of cultural products can be characterized as a Power Law, Pareto, or Zipf distribution. This is also known as the 80/20 rule or “The Long Tail.” That is, a small number of the cultural products in question (be they books, Web sites, TV shows, songs, scholarly articles) reach a very wide audience, while most of those products reach a very small audience. The distribution is relatively sharply divided between “big hits” (the head) and everything else (the tail).

Robert K. Merton, for example, used a distribution like this in the sociology of science to show that a small number of scientific publications get almost all of the citations.

Arguments about this distribution are widespread (see Benkler, Webster, Adams & Huberman, Barabasi & Albert, and more). Yet pointing out this distribution is not a very useful way to characterize what is going on in these industries. To say that something fits a power law distribution doesn’t give us much traction to make a normative argument. What distribution would be ideal? How should we draw the line to make the culture we want to have?

[The power law distribution. Click to enlarge.]

[A nitpicker’s aside: Note that sometimes these curves are shown as probability distributions and other times they are a sorted list of different cultural products along the bottom. These are somewhat sloppily used interchangeably but they produce different curves.]

We know it would be problematic to have a distribution characterized by a dot at the upper left and nothing else. (That could be the Kim Jong-Il distribution — there’s only one thing to watch and everyone has to watch it.)

We also know it would be problematic to have a distribution characterized by a line running along the bottom or a dot at the lower-right (the depiction would depend on whether it was a probability distribution or a sorted list of different cultural products). This could be the head-in-the-sand distribution. In that model I would produce media that you would watch, you would produce media that someone else would watch. That someone else would produce media for yet another person, and so on. We would have no commonality in our media consumption.

Indeed, how we think about the distribution varies a lot depending on the perspective we bring to it. Some Internet scholars and others see the right side as good — as “diversity” — and the left side as bad — as “concentration” (Benkler, Anderson). At the same time, some media studies scholars see the right side as bad — as “fragmentation” — and the left side as good — as “communal experience.” It is impossible to have a culture without shared experience (Gitlin, Turow, Katz).

If this isn’t a good way to characterize our culture… what is? Pareto distributions are often used for analyses of income inequality; in fact this is why Pareto first came up with it. E.g., The top x% of the population controls y% of the wealth. If you were doing an analysis of income stratification, this part would be analyzing the distribution. Don’t stop there! No analysis of stratification is complete when it focuses only on distribution: you also have to look at mobility. In other words, it’s not (just) the shape of the curve that matters but if you can move up it. Can, as John Stuart Mill once hoped, your good idea for a cultural product rise on its own merits? Research on “cultural mobility” in this context mostly isn’t done.

If we look at the curve with mobility in mind, we see a number of possible bottlenecks that could be just as potent as the old “mass media” distribution bottleneck. One is distribution (again), one is search (or recommendation), and one is something that is still messy in my mind that I’ll call genre.

IV. The New Bottlenecks

As the Berkman Luncheon Series encourages the presentation of works in progress, these are provisional concerns that I hope to use to shape a research project. (Note also that in this talk I’ll spend more time with distribution that with the other two just because I’m farther along in thinking about that one.)

Bottleneck #1: Distribution (again)

We thought the distribution bottleneck was over but it may be that it is reappearing. The “long tail” distribution may in fact characterize two different video distribution networks: one for the head and one for the tail. In effect, we are building two Internets for the distribution of video. Let me explain.

If I want to show my baby pictures to a few friends it is relatively straightforward. I can host videos on my own web server or on a third-party video sharing site.

However, if I want to show Michael Phelps winning Olympic gold medals to a huge audience the Internet has evolved in such a way that NBC needs to enter into an agreement with a distribution intermediary for a large audience to work. They need an edge cache or a content distribution network (in this example, they used Limelight).

If you try to show Michael Phelps from a web server under your desk it wouldn’t work for a number of reasons. Primarily because of source congestion. Although you as a viewer may have the bandwidth on your cruddy DSL line to watch Michael Phelps from my Web server I don’t have the bandwidth to my Web server to serve that video very many times simultaneously. So if I try to serve a large simultaneous audience from my Web server I will quickly run out of capacity as the network around the source of the video fills up. (In textual contexts this has been called the slashdot effect.)

The way that you distribute videos that are not popular and the way that you distribute videos that are popular is very different.

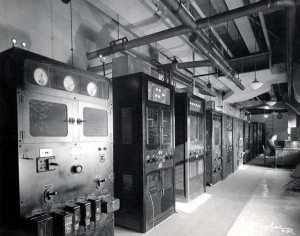

[Factories of culture: an RCA transmitter in 1936.

Image courtesy The Early Television Museum.]

Break for history: When Adorno was getting exercised about the culture industries he thought that it was fascinating that there were now these “factories of culture” — essentially industrial sites like this RCA transmitter in 1936. They were very expensive to build and operate and you or I couldn’t get access to them. Mass culture was an industrialized form of culture that required a lot of capital to participate. But you know, that RCA transmitter in 1936 looks a lot like a Google data center today, if you squint.

There’s an ecology of companies that offer this industrial distribution service on the Internet. They guarantee the availability of video for large audiences. By and large, you can’t use this infrastructure because these companies won’t deal with individual consumers (there are one or two exceptions like Amazon Web Services). Akamai leads this market.

You could say that television stations were the edge caches of the 70s, 80s, and 90s. We are now recreating that distribution network with video on the Internet.

It’s important to remember that the mass audience isn’t the default situation, even with “old” television. Sterne’s excellent article (“Television Under Construction”) notes that we now think of television as being defined by the “mass audience,” but historically in early television there was no mass audience. The mass audience was also not technologically determined by the apparatus of TV. In early television there was no network capable of carrying video across the US, and there was no video tape on which to record it. That network and video tape (and later satellites) was elaborately constructed at great expense because the industry thought that having everyone in the country watch the same thing at the same time would be a good idea. Their hope was to generate a national audience for advertising.

Indeed, Sterne says, before about 1962 television was local. It took lobbying and investment by AT&T among others to build this elaborate distribution infrastructure that gave television the “head” that we now think of as the head in the power law or Pareto distribution. If the industry built this distribution infrastructure once for TV, it can be built again on the Internet. Just as television isn’t naturally a mass medium, the Internet isn’t naturally diverse.

The Internet is supposed to provide all kinds of economies of distribution that make it cheaper than television, but at least for the case of popular content it is not clear that the Internet is particularly more efficient. We know that television is excellent at distributing the same thing to a massive audience at the same time. It’s very difficult to compare the distribution costs of traditional television and Internet video distribution for a variety of reasons, however the current going rate for the distribution of a few minutes of video late at night on TV vs. via a content distribution network like Amazon Web Services are actually quite comparable.

Bottleneck #2: Search

Even beyond distribution it is now becoming clear that there are other important bottlenecks in video distribution. (This section is indebted to Introna & Nissenbaum’s pioneering argument in “The Politics of Search” ten years ago and is an extension of that argument.) This bottleneck really shouldn’t be that surprising.

We know that search algorithms like PageRank are essentially voting algorithms that push people toward popular content. They are much more effective than the prior generation of algorithms, but this may be at the expense of finding unpopular or obscure content that matches the keywords you entered.

Beyond keyword search, how do we find what to watch on the Internet? It is now clear that two important sources for what to watch are (1) front page real estate in the “Featured Videos” section and (2) the short list of “Related” or recommended videos that appear after the conclusion of a video you are watching, or (on some sites) in the sidebar. In popular press treatments of new online forms of distribution like Anderson’s “The Long Tail,” it is posited that the new recommender systems at work on amazon.com, YouTube, and elsewhere are fundamentally democratizing because they push traffic down the tail. They tailor recommendations so that niche videos, for example, can find their own small but perfect audience.

From what we know about these algorithms there is no particular reason that the algorithms would do this unless they were intentionally optimized to do so. They could also be optimized to, say, drive traffic toward videos that would make the company doing the recommending more money. Given YouTube’s drastic expansion of licensing deals with mainstream media franchises, this bears some investigation.

If you read the computer science literature about recommendation systems you get guesses in parenthetical asides that at least some of this is going on. Google Labs doesn’t publish much about this but recent papers remark on the importance of popularity for recommendation systems, and at times lament the difficulty that personalized recommendations have in moving beyond the popular. We don’t know for sure, but algorithms may use the “Featured Videos” flag (or equivalent).** The Featured Videos list does not appear to be machine generated and often features videos that are produced by media partners.

Some more information can be gleaned from the active YouTube reverse-engineering community. Steven Wittens’s excellent blog post about YouTube’s recommendation algorithms last year, for instance, finds that after you watch a video on YouTube, YouTube recommends more videos that are about as popular as the one you just watched. So if you are watching popular videos your recommendations will also be popular videos. If you are watching niche videos your recommendations will be niche videos. This is not the same as the algorithm pushing traffic down the tail!

In addition, Wittens finds that in some instances YouTube will recommend more popular videos than the one you were watching, but it is much less common for it to recommend less-popular videos. That means the sum effect of the algorithm may in fact be pushing people toward more popular videos.***

Bottleneck #3: Genre

Maybe I was naiive about online video. I expected that when the distribution bottleneck changed, video would change. It’s true, video is changing, but we can argue about how new it is. Much of the non-traditional new Internet content looks a lot like America’s Funniest Home Videos.

That is to say, it is fascinating that much of the video on YouTube and other online outlets does in fact depend quite heavily on existing TV and movie genres for how video is supposed to look. Parodies of television sitcoms. Parodies of news shows. Music videos. And so on.

The structure of the 30 minute (or 18 minute with commercials) sitcom has been naturalized over time but there is nothing natural about it, so I am somewhat surprised that many shows seem to so strictly ape existing formats. It could be that the genres themselves are hard to depart from because they draw an audience by being recognizable to them.

This is kind of a meta-bottleneck: How we think about the other bottlenecks depends on this one. It matters quite a bit in our mobility analysis or in our study of search and recommendation if people are independently producing content that looks just like what came before.

There may be a lot of mobility and the recommendation systems that exist are promoting new voices… but if the new voices say the same thing as the old ones the consequence for the transformation of video is very different. In this scenario YouTube becomes the A&R (artist & repertoire department) for the mainstream media. YouTube and outlets like it save money on production budgets by eliminating the need for, say, expensive pilots. But the new online video otherwise doesn’t change anything. (Mark Andrejevic has made this point as well.) This is one model for the future of television, but it isn’t a revolution.

It would be easier to argue about the future genres of video if we had some clearer idea of what kinds of things we want to valorize. What is the goal of a revolutionized video? In the logic of remix (Lessig, Jenkins), it is the process that matters and not the content. The videos may ape mainstream forms but they provide an important creative outlet to reshape those forms with non-mainstream messages.

More philosophically, Adorno & Horkheimer famously said that the products of mass culture are fundamentally interchangeable. It’s hard to argue that one cute kitten (the organic grassroots-produced countercultural kitten video) deserves to prevail over the the Viacom-produced mass media kitten. They’re kittens. We could say the same thing about boy bands (or anyway Adorno would). So let me put a question to you that I also posted on my blog a while ago: what is the most virtuous Internet video? It’s a hard question to answer if we exclude news, as it is much easier to make normative arguments about news.

Is there an emerging genre on Internet video that, like LIFE magazine’s photojournalism, is worth preserving? To use this kind of reasoning you’d need to find a genre that is not going to be well-served by advertising-supported media, and one that is popular. I don’t know the answer. One possible winner of my earlier contest is “In My Language” (suggested by Kevin Hamilton). This is a video by an autistic child trying to depict the experience of autism. It has about 900,000 views as I write this.

V. Conclusion

I fear that television is evolving backwards. While online video experienced a few years of freedom, trends are now pointing toward a retrenched mass media that may restrict future innovation and participation in online video — at least video that reaches a wide audience.

The items I’ve covered in this talk are currently operating at the level of anecdote and suspicion. It isn’t clear how video is actually evolving online as studies of these phenomena are not (so far) being done. I gave this talk in an attempt to conceptualize and launch new research that can help us understand the shifts — if any — in our mediated culture.

I provisionally identified three bottlenecks that seem just as potent as our old concerns about the distribution limits of the “mass” media. It’s crucial to acknowledge that this is a fast-changing area and the battle (whichever side you root for) is far from lost or won. In distribution, for instance, researchers at Princeton are developing edge caching systems that potentially remove the need for content distribution networks like Akamai. In search, Pasquale (and others) have emphasized the need for algorithm transparency as a public policy solution to the search/recommendation bottleneck.

In genre I’m less sure of a positive or optimistic concluding remark to include. One answer may be that new genres have emerged on YouTube but we are too conservative to see it. In a few years, looking back the Internet could be seen as pioneering video genres that we who remembered television didn’t care about. The transformed video marketplace could be Channimals (icanhascheezburger), pratfalls (like failblog), vlogs, and annotated video game commentary. There is some movement in that direction, as networks like Do Not Disturb TV have shown (a cable channel filled with YouTube videos of pratfalls and talking dogs).

To conclude, I worry about the future of non-traditional, non-commercial video on the Internet. At the moment, charlie bit my finger (4.5m views) has no public advocate. Just twelve months ago the idea that he needed one seemed preposterous. Now I’m not so sure. I’d love your comments on my worries.

—

* N.B. there may be other reasons Google wants to lose money on YouTube (leverage in negotiating peering agreements), or it may in fact not be losing money.

** or the “Featured Videos” list may be such a strong influence on how people find videos that popularity and listing on the “Featured Videos” list may be synonymous.

*** in my spoken talk I became carried away and used the word “never” when talking about this — that was too strong.

—

UPDATE: Fixed images so that they display properly.

April 14th, 2010 at 10:49 am

[…] group was gathered by Christian Sandvig, an authority on the topic. Christian gave a great talk last week in the Berkman luncheon series. Check it […]

April 14th, 2010 at 1:42 pm

[…] Sandvig had an interesting lecture, The Television Cannot Be Revolutionized, in which he predicts that online video will become much like TV, and claims there is an ongoing […]

April 15th, 2010 at 8:57 am

[…] is merely five years old, launched with the birth of YouTube. Nonetheless, Christian Sandvig offers a somewhat hysterical judgment on the impending ‘retrenchment’ of online video by the old mass media […]

April 23rd, 2010 at 9:22 am

[…] see also Christian Sandvig, The Television Cannot be Revolutionized […]

June 8th, 2010 at 9:00 am

great post thanks http://twitter.com/gr8p