Show and Tell: Algorithmic Culture

Tuesday, March 25th, 2014(or, What you need to know about “puppy dog hate”)

(or, “It’s not that I’m uninterestedin hygiene…”)

Last week I tried to get a group of random sophomores to care about algorithmic culture. I argued that software algorithms are transforming communication and knowledge. The jury is still out on my success at that, but in this post I’ll continue the theme by reviewing the interactive examples I used to make my point. I’m sharing them because they are fun to try. I’m also hoping the excellent readers of this blog can think of a few more.

I’ll call my three examples “puppy dog hate,” “top stories fail,” and “your DoubleClick cookie filling.” They should highlight the ways in which algorithms online are selecting content for your attention. And ideally they will be good fodder for discussion. Let’s begin:

Three Ways to Demonstrate Algorithmic Culture

(1.) puppy dog hate (Google Instant)

You’ll want to read the instructions fully before trying this. Go to http://www.google.com/ and type “puppy”, then [space], then “dog”, then [space], but don’t hit [Enter]. That means you should have typed “puppy dog ” (with a trailing space). Results should appear without the need to press [Enter]. I got this:

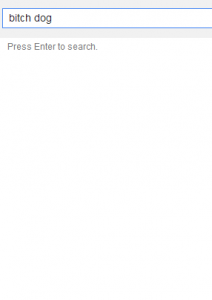

Now repeat the above instructions but instead of “puppy” use the word “bitch” (so: “bitch dog “). Right now you’ll get nothing. I got nothing. (The blank area below is intentionally blank.) No matter how many words you type, if one of the words is “bitch” you’ll get no instant results.

What’s happening? Google Instant is the Google service that displays results while you are still typing your query. In the algorithm for Google Instant, it appears that your query is checked against a list of forbidden words. If the query contains one of the forbidden words (like “bitch”) no “instant” results will be shown, but you can still search Google the old-fashioned way by pressing [Enter].

This is an interesting example because it is incredibly mild censorship, and that is typical of algorithmic sorting on the Internet. Things aren’t made to be impossible, some things are just a little harder than others. We can discuss whether or not this actually matters to anyone. After all, you could still search for anything you wanted to, but some searches are made slightly more time-consuming because you will have to press [Enter] and you do not receive real-time feedback as you construct your search query.

It’s also a good example that makes clear how problematic algorithmic censorship can be. The hackers over at 2600 reverse engineered Google Instant’s blacklist (NSFW) and it makes absolutely no sense. The blocked words I tried (like “bitch”) produce perfectly inoffensive search results (sometimes because of other censorship algorithms, like Google SafeSearch). It is not clear to me why they should be blocked. For instance, anatomical terms for some parts of the female anatomy are blocked while other parts of the female anatomy are not blocked.

Some of the blocking is just silly. For instance, “hate” is blocked. This means you can make the Google Instant results disappear by adding “hate” to the end of an otherwise acceptable query. e.g., “puppy dog hate ” will make the search results I got earlier disappear as soon as I type the trailing space. (Remember not to press [Enter].)

This is such a simple implementation that it barely qualifies as an algorithm. It also differs from my other examples because it appears that an actual human compiled this list of blocked words. That might be useful to highlight because we typically think that companies like Google do everything with complicated math and not site-by-site or word-by-word rules–they have claimed as much, but this example shows that in fact this crude sort of blacklist censorship still goes on.

Google does censor actual search results (what you get after pressing [Enter]) in a variety of ways but that is a topic for another time. This exercise with Google Instant at least gets us started thinking about algorithms, whose interests they are serving, and whether or not they are doing their job well.

(2.) Top Stories Fail (Facebook)

In this example, you’ll need a Facebook account. Go to http://www.facebook.com/ and look for the tiny little toggle that appears under the text “News Feed.” This allows you to switch between two different sorting algorithms: the Facebook proprietary EdgeRank algorithm (this is the default), and “most recent.” (On my interface this toggle is in the upper left, but Facebook has multiple user interfaces at any given time and for some people it appears in the center of the page at the top.)

Switch this toggle back and forth and look at how your feed changes.

What’s happening? Okay, we know that among 18-29 year-old Facebook users the median number of friends is now 300. Even given that most people are not over-sharers, with some simple arithmetic it is clear that some of the things posted to Facebook may never be seen by anyone. A status update is certainly unlikely to be seen by anywhere near your entire friend network. Facebook’s “Top Stories” (EdgeRank) algorithm is the solution to the oversupply of status updates and the undersupply of attention to them, it determines what appears on your news feed and how it is sorted.

We know that Facebook’s “Top Stories” sorting algorithm uses a heavy hand. It is quite likely that you have people in your friend network that post to Facebook A LOT but that Facebook has decided to filter out ALL of their posts. These might be called your “silenced Facebook friends.” Sometimes when people do this toggling-the-algorithm exercise they exclaim: “Oh, I forgot that so-and-so was even on Facebook.”

Since we don’t know the exact details of EdgeRank, it isn’t clear exactly how Facebook is deciding which of your friends you should hear from and which should be ignored. Even though the algorithm might be well-constructed, it’s interesting that when I’ve done this toggling exercise with a large group a significant number of people say that Facebook’s algorithm produces a much more interesting list of posts than “Most Recent,” while a significant number of people say the opposite — that Facebook’s algorithm makes their news feed worse. (Personally, I find “Most Recent” produces a far more interesting news feed than “Top Stories.”)

It is an interesting intellectual exercise to try and reverse-engineer Facebook’s EdgeRank on your own by doing this toggling. Why is so-and-so hidden from you? What is it they are doing that Facebook thinks you wouldn’t like? For example, I think that EdgeRank doesn’t work well for me because I select my friends carefully, then I don’t provide much feedback that counts toward EdgeRank after that. So my initial decision about who to friend works better as a sort without further filtering (“most recent”) than Facebook’s decision about what to hide. (In contrast, some people I spoke with will friend anyone, and they do a lot more “liking” than I do.)

What does it mean that your relationship to your friends is mediated by this secret algorithm? A minor note: If you switch to “most recent” some people have reported that after a while Facebook will switch you back to Facebook’s “Top Stories” algorithm without asking.

There are deeper things to say about Facebook, but this is enough to start with. Onward.

(3.) Your DoubleClick Cookie Filling (DoubleClick)

This example will only work if you browse the Web regularly from the same Web browser on the same computer and you have cookies turned on. (That describes most people.) Go to the Google Ads settings page — the URL is a mess so here’s a shortcut: http://bit.ly/uc256google

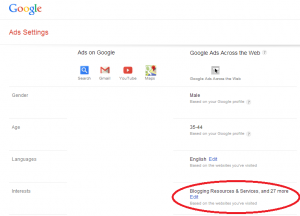

Look at the right column, headed “Google Ads Across The Web,” then scroll down and look for the section marked “Interests.” The other parts may be interesting too, such as Google’s estimate of your Gender, Age, and the language you speak — all of which may or may not be correct. Here’s a screen shot:

If you have “interests” listed, click on “Edit” to see a list of topics.

What’s Happening? Google is the largest advertising clearinghouse on the Web. (It bought DoubleClick in 2007 for over $3 billion.) When you visit a Web site that runs Google Ads — this is likely quite common — your visit is noted and a pattern of all of your Web site visits is then compiled and aggregated with other personal information that Google may know about you.

What a big departure from some old media! In comparison, in most states it is illegal to gather a list of books you’ve read at the library because this would reveal too much information about you. Yet for Web sites this data collection is the norm.

This settings page won’t reveal Google’s ad placement algorithm, but it shows you part of the result: a list of the categories that the algorithm is currently using to choose advertising content to display to you. Your attention will be sold to advertisers in these categories and you will see ads that match these categories.

This list is quite volatile and this is linked to the way Google hopes to connect advertisers with people who are interested in a particular topic RIGHT NOW. Unlike demographics that are presumed to change slowly (age) or not to change at all (gender), Google appears to base a lot of its algorithm on your recent browsing history. That means if you browse the Web differently you can change this list fairly quickly (in a matter of days, at least).

Many people find the list uncannily accurate, while some are surprised at how inaccurate it is. Usually it is a mixture. Note that some categories are very specific (“Currency Exchange”), while others are very broad (“Humor”). Right now it thinks I am interested in 27 things, some of them are:

- Standardized & Admissions Tests (Yes.)

- Roleplaying Games (Yes.)

- Dishwashers (No.)

- Dresses (No.)

You can also type in your own interests to save Google the trouble of profiling you.

Again this is an interesting algorithm to speculate about. I’ve been checking this for a few years and I persistently get “Hygiene & Toiletries.” I am insulted by this. It’s not that I’m uninterested in hygiene but I think I am no more interested in hygiene than the average person. I don’t visit any Web sites about hygiene or toiletries. So I’d guess this means… what exactly? I must visit Web sites that are visited by other people who visit sites about hygiene and toiletries. Not a group I really want to be a part of, to be honest.

These were three examples of algorithm-ish activities that I’ve used. Any other ideas? I was thinking of trying something with an item-to-item recommender system but I could not come up with a great example. I tried anonymized vs. normal Web searching to highlight location-specific results but I could not think of a search term that did a great job showing a contrast. I also tried personalized twitter trends vs. location-based twitter trends but the differences were quite subtle. Maybe you can do better.

In my next post I’ll write about how the students reacted to all this.

(This was also cross-posted to The Social Media Collective.)