Lately Ron Lieber (@ronlieber), the Your Money editor and columnist for the New York Times, has been posting pieces that expose a dysfunction in the car rental marketplace — one that is punishing innovators that take the sides of customers.  The story is still unfolding, which gives us the opportunity to visit and think through some VRM approaches to the problem.

The story is still unfolding, which gives us the opportunity to visit and think through some VRM approaches to the problem.

Ron’s first piece is a column titled “A Rate Sleuth Making Rental Car Companies Squirm,” on February 17, and his second is a follow-up column, “Swatting Down Start-Ups That Help Consumers,” on April 6. Both stories are about AutoSlash, a start-up that constantly researches and re-books car rentals for you, until you get the lowest possible price from one of them. That company wins the business, at a maximized discount. The others all lose. This is good for the customer, if all the customer cares about is price. It’s bad for the agencies, since the winner is the one that makes the least amount of money on the rental.

In the second piece, Ron explains,

The customer paid nothing for the service, and AutoSlash got a commission from Travelocity, whose booking engine it rented. This was so delightful that it felt as if it might not last, and I raised the possibility that participating companies like Hertz and Dollar Thrifty would bail out, as Enterprise and the company that owns Avis and Budget already had. I encouraged readers to patronize the participants in the meantime to reward them for playing along. Well, they’ve stopped playing. In the last couple of weeks, Hertz and the company that owns both Dollar and Thrifty have turned their backs on AutoSlash — and for good reason, according to Hertz: AutoSlash seems to have been using discount codes that its customers were not technically eligible for.

On its site, AutoSlash put things this way (at that last link):

We’re disappointed that these companies have now chosen to reverse course and adopt this anti-consumer position, after having participated in this site since its launch in mid-2010. Apparently, with more customers booking reservations through our service, they felt they could no longer support our consumer-friendly model of automatically finding the best discount codes and re-booking when rates drop. AutoSlash will not waver in our objective to help people get a great deal on their rentals. We have exciting product plans on the horizon to make our site even more useful to you..

On the same day as his second column, Ron ran a blog post titled “AutoSlash, AwardWallet, MileWise and the Travel Bullies,” in which he points to airlines as another business with the same problems — and the same negative responses to rate-sleuths:

American Airlines and Southwest Airlines have made it clear that they do not want any third party Web site taking customers’ AAdvantage or Rapid Rewards frequent flier balances and putting them on a different site where people can view them alongside those from other loyalty programs. This comes at a loss of convenience to customers, and the airlines make all sorts of specious arguments about why this is necessary. Meanwhile, sites like AwardWallet, MileWise and MilePort are less useful than they would be otherwise without a full lineup of airline account information available. But there’s a the bigger question here: Why can’t the big travel players simply fix their archaic business models and add these nifty features to their Web sites and stop spending energy ganging up on start-ups who unmask their flaws?

The answer comes from Scott Adams, of Dilbert fame. By Scott’s definition, the big travel players are a “confusopoly.” They see what Ron calls a “flaw” — burying the customer in a snowstorm of discounts intended both to entice and to confuse — as a feature, rather than a bug. Here’s Scott:

A confusopoly is any group of companies in a particular industry that intentionally confuses customers about their pricing plans and products. Confusopolies do this so customers don’t know which one of them is offering the best value. That way every company gets a fair share of the confused customers and the industry doesn’t need to compete on price. The classic examples of confusopolies are phone companies, insurance companies, and banks.

Car rental agencies are clearly confusopolies. So are airlines. Dave Barry explains how it is that no two passengers on one airplane pay the same price for a seat:

Q. So the airlines use these cost factors to calculate a rational price for my ticket?

A. No. That is determined by Rudy the Fare Chicken, who decides the price of each ticket individually by pecking on a computer keyboard sprinkled with corn. If an airline agent tells you that they’re having “computer problems, ” this means that Rudy is sick, and technicians are trying to activate the backup system, Conrad the Fare Hamster.

There are a few exceptions. One is Southwest, which competes through relatively simple seat pricing and unconfusing policies (e.g. no seat assignments and “bags fly free”). But even Southwest plays confusing games. For example, I just went to Southwest to make sure the URL was right (it used to be iflyswa.com, as I recall), and got intercepted by a promo offer, for a gift card. So, for research purposes, I filled it out. That got me to this page here:

Note that there is no place to take the last step. The “Your Info Below” space is blank. Everywhere I click, nothing happens. Fun. (Is it possible this isn’t from Southwest at all? Maybe somebody from Southwest can weigh in on that.)

Note that there is no place to take the last step. The “Your Info Below” space is blank. Everywhere I click, nothing happens. Fun. (Is it possible this isn’t from Southwest at all? Maybe somebody from Southwest can weigh in on that.)

So, a confusopoly.

What can we do? Governments fix monopolies by breaking them up. But confusopolies come pre-broken. That’s how they work. There is no collusion between Hertz and Budget, or between United and American. They are confusing on purpose, and independently so. No doubt they have their confusing systems fully rationalized, but that doesn’t make the confusion less real for the customer, or less purposeful for the company.

Let’s look a bit more closely at three problems endemic to the car rental business, and contribute to the confusopoly.

- Cars, like airlines and their seats, have become highly generic, and therefore commoditized. Even if there is a difference between a Chevy Cruze and a Ford Focus, the agencies mask it by saying what you’ll get is some model of some maker’s car, “or similar.” (I’ve always thought one of the car makers ought to just go ahead and make a car just for rentals, and brand it the “Similar.”)

- The non-price differentiators just aren’t different enough. For example, I noticed that Enterprise lately forces its workers to go out of their way to be extra-personal. They come out from behind the counter, shake your hand, call you by name, ask about your day, and so on. Which is all nice, but not nicer for most of us than a lower price than the next agency.

- The agencies’ CRM (Customer Relationship Management) systems don’t have enough to work with. While Enterprise is singled out here and here for having exceptional CRM, all these systems today operate entirely on the vendors’ side. Not on yours or mine. Each of is silo’d. How each of us relates to any one agency doesn’t work with the others. This is an inconvenience for us, but not for the agencies, at least as far as they know. And, outside their own silo’d systems, they can’t know much, except maybe through intelligence they buy from “big data” mills. But that data is also second-hand. No matter how “personalized” that data is, it’s about us, not directly by us or from us, by our own volition, and from systems we control.

A few years ago I began to see these problems as opportunities. I thought, Why not build new tools and systems for individual customers, so they can control their own relationships, in common and standard ways, with multiple vendors? And, What will we call the result, once we have that control? My first answer to those questions came in a post for Linux Journal in March, 2006, titled The Intention Economy. Here are the money grafs from that one:

The Intention Economy grows around buyers, not sellers. It leverages the simple fact that buyers are the first source of money, and that they come ready-made. You don’t need advertising to make them. The Intention Economy is about markets, not marketing. You don’t need marketing to make Intention Markets. The Intention Economy is built around truly open markets, not a collection of silos. In The Intention Economy, customers don’t have to fly from silo to silo, like a bees from flower to flower, collecting deal info (and unavoidable hype) like so much pollen. In The Intention Economy, the buyer notifies the market of the intent to buy, and sellers compete for the buyer’s purchase. Simple as that. The Intention Economy is built around more than transactions. Conversations matter. So do relationships. So do reputation, authority and respect. Those virtues, however, are earned by sellers (as well as buyers) and not just “branded” by sellers on the minds of buyers like the symbols of ranchers burned on the hides of cattle.

The Intention Economy is about buyers finding sellers, not sellers finding (or “capturing”) buyers. In The Intention Economy, a car rental customer should be able to say to the car rental market, “I’ll be skiing in Park City from March 20-25. I want to rent a 4-wheel drive SUV. I belong to Avis Wizard, Budget FastBreak and Hertz 1 Club. I don’t want to pay up front for gas or get any insurance. What can any of you companies do for me?” — and have the sellers compete for the buyer’s business.

Thanks to work by the VRM (Vendor Relationship Management) development community, The Intention Economy is now a book, with the subtitle When Customers Take Charge, due out from Harvard Business Review Press on May 1. (You can pre-order it from Amazon, and might get it sooner that way.)

Having sellers compete for a buyer’s business (to serve his or her signaled intent) is what we now call a Personal RFP. (Scott Adams calls it “broadcast shopping.”) What it requires are two things that are now on their way. One is tools. The other is infrastructure. As a result of both, we will see emerge a new class of market participant: the fourth party. It’s a role AutoSlash can play, if it’s willing to play a new game rather than just gaming the old one.

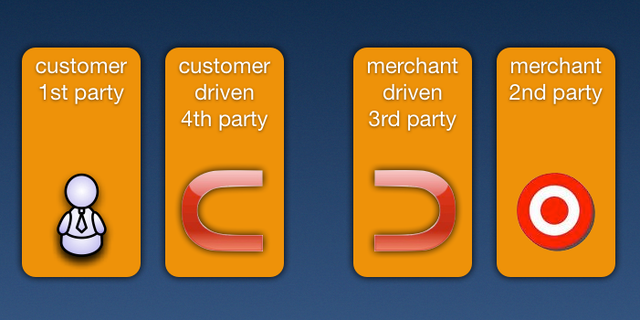

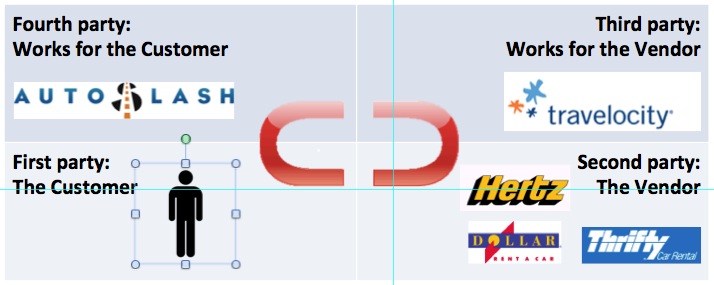

The new game is serving as a real agent of customers, rather than just as a lead-generating system for third parties such as Travelocity, or a pest for second parties such as Hertz, Dollar and Thrifty. Fourth parties are businesses that side with customers rather than with vendors or third parties. Think of them as third parties that work for you and me. In this post, Phil Windley of Kynetx (a VRM developer), represents the four parties graphically:  Fourth parties can also serve as agents for improving actual relationships (rather than coercive ones). The two magnets are “r-buttons” (explained most recently here), which represent the buyer and the seller, and (as magnets) depict both attraction and openness to relationship. They are simple symbols one can also type, like this: ⊂ ⊃. (The ⊂ represents you, or the buy side, while the ⊃ represents vendors and their allied third parties, or the sell side.) Here is another way of laying these out, with some names that have already come up:

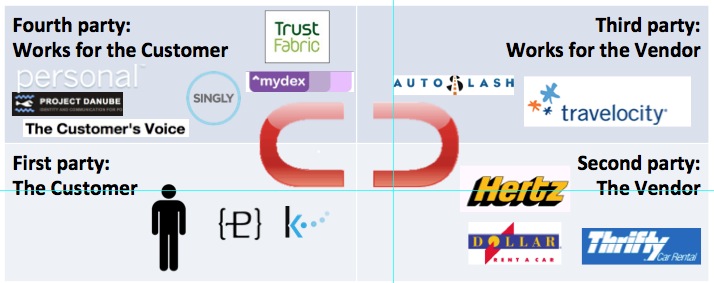

Fourth parties can also serve as agents for improving actual relationships (rather than coercive ones). The two magnets are “r-buttons” (explained most recently here), which represent the buyer and the seller, and (as magnets) depict both attraction and openness to relationship. They are simple symbols one can also type, like this: ⊂ ⊃. (The ⊂ represents you, or the buy side, while the ⊃ represents vendors and their allied third parties, or the sell side.) Here is another way of laying these out, with some names that have already come up:  As of today AutoSlash presents itself as an agent of the customer, but business-wise it’s an accessory to a third party, Travelocity. While Travelocity could be a fourth party as well, it is still too tied into the selling systems of the car rental agencies to make the move. (If I’m wrong, tell me how.) Now, what if AutoSlash were to join a growing young ecosystem of VRM companies and projects working on the customer’s side? Here is roughly how that looks today:

As of today AutoSlash presents itself as an agent of the customer, but business-wise it’s an accessory to a third party, Travelocity. While Travelocity could be a fourth party as well, it is still too tied into the selling systems of the car rental agencies to make the move. (If I’m wrong, tell me how.) Now, what if AutoSlash were to join a growing young ecosystem of VRM companies and projects working on the customer’s side? Here is roughly how that looks today:  AutoSlash is over there on the right, on the sell side. On the buy side, in the fourth party quadrant, are Personal, ProjectDanube, TrustFabric, MyDex, Singly and The Customer’s Voice. All provide ways for individuals to manage their own data, and (actually in some cases, potentially in others) relationships with second and third parties, on behalf of the customer. If you look at just the right two quadrants, on the ⊃ side, the car rental agencies fired AutoSlash for breaking their system. That’s one more reason for AutoSlash to come over to the ⊂ side and start operating unambiguously as a pure fourth party.

AutoSlash is over there on the right, on the sell side. On the buy side, in the fourth party quadrant, are Personal, ProjectDanube, TrustFabric, MyDex, Singly and The Customer’s Voice. All provide ways for individuals to manage their own data, and (actually in some cases, potentially in others) relationships with second and third parties, on behalf of the customer. If you look at just the right two quadrants, on the ⊃ side, the car rental agencies fired AutoSlash for breaking their system. That’s one more reason for AutoSlash to come over to the ⊂ side and start operating unambiguously as a pure fourth party.

I believe that’s what RentalCarMagic already does. While their service is superficially similar to AutoSlash’s (they book you the lowest prices), they clearly work for you (⊂) as a fourth party and not for the agencies (⊃) as a third party. What makes them unambiguously a fourth party is the fact that you pay them. Here are their rates.

For controlling multiple relationships, however, you still need tools other than straightforward one-category services (such as AutoSlash and RentalCarMagic). One circle around those tools is what KuppingerCole calls Life Management Platforms. Another, from Peter Vander Auwera of SWIFT is The Programmable Me. These (among much more) will be the subject of sessions at the European Identity and Cloud Conference (EIC) this week in Munich. (I’ll be flying there shortly from Boston.) I’ll be participating in those. So will Phil Windley of Kynetx, who has detailed a concept called the “Personal Event Network,” aka the “Personal Cloud.” Links, in chronological order:

- Ways, Not Places

- Protocols and Metaprotocols: What is a Personal Event Network?

- KRL, Data and Personal Clouds

- Personal Clouds as General Purpose Computers

- Personal Clouds Need a Cloud Operating System

- The Foundational Role of Identity in Personal Clouds

- Data Abstractions for Richer Cloud Experiences

- A Programming Model for Personal Clouds

- Federating Personal Clouds

This is thinking-in-progress about work-in-progress, by a Ph.D. computer scientist and college professor as well as an entrepreneur and a very creative inventor. (By the way, KRL and its rules engine are open source. That’s cool too.)

If I have time later I’ll unpack some of this, and start knitting the connections between what Phil’s talking about and what others (especially Martin Kuppinger of KuppingerCole, who will be writing and posting more about Life Management Platforms) are also bringing to the table here.

In particular I will bring up the challenge of fixing the car rental agency market. What can we do, not only for the customer and for his or her fourth parties (the ⊂ side) but for everybody on the third and second party (⊃) side?

And what changes will have to take place on the ⊃ side once they find they need to truly differentiate, in distinctive and non-gimmicky ways? What effect will that have on the car makers as well?

When I started down this path, back in 2006, I had a long conversation with a top executive at one of the car rental companies. What sticks with me is that these guys don’t have it easy. Among other things, he told me that the car companies mostly don’t like the car rental business because it turns drivers off to many of the cars they rent, and the car companies don’t make much money on the cars either. Can that be fixed too? I don’t know, but I’d like customers and their fourth parties to help.

How about through true personalization, in response to actual demand by individual customers, such as I suggested in 2006?

How about through new infrastructural approaches, such as the Digital Asset Grid?

Hertz, Budget’s and Enterprise’s own CRM and loyalty systems are not going to go away. Nor will the ways they all have of identifying us, and authenticating us. How can we embrace those, even as we work to obsolete them?

There are two worlds overlapping here: the one we have, and the one we’re building that will transcend and subsume the one we have.

The one we have is a “free market” with a “your choice of captor” model. It is for violating this model that AutoSlash was fired as a third party by the car rental agencies.

The one we’re building is a truly free market, in which free customers prove more valuable than captive ones. We need to make the pudding that proves that principle.

And we’re doing that. But it’s not a simple, an easy, or even a coordinated process. The good thing is, it’s already underway, and has been for some time.

Looking forward to seeing you at EIC in Munich, and/or at the other events that follow, in London and Mountain View:

- European Identity and Cloud Conference, Munich, April 17-20.

- Intention Economy Mashup Event London, Innovation Warehouse, 1 East Poultry Avenue, London. EC1A 9PT 4:30-9:30pm, Monday, 23 April.

- VRM and CRM Inter-op London 2012 London , EC1A 9PT Tuesday, April 24, 2012 from 9:00 AM to 1:00 PM (GMT)

- Pre-IIW VRM workshop at Ericsson, 200 Holger Way (Zanker & 237), San Jose, CA 95134, 9am-5pm April 30..

- IIW14 Internet Identity Workshop #14, Mountain View, CA, May 1-3.

Meanwhile, a last word, in respect to what Bart Stevens says below. Clearly the car rental business needs to move out of the confusopoly model, and to differentiate on more than price. To some degree they already do, but price is the primary driver for most customers. (And I’d welcome correction on that, if it’s wrong.) We have a lot to learn from each other.