One of the most mind-blowing one-liners I ever heard tossed was this one:

“All the significant trends start with technologists.”

It was uttered by Marc Andreessen during an interview I did with him for Linux Journal, in May 1998, for the August issue of the magazine, following up on Netscape’s open source release of Mozilla. The title of the piece was Betting on Darwin. It’s still up at that link, and an interesting piece of history.

That one-liner knocked me over because it is so obvious and true, yet easily overlooked. It is also exactly the reason I started ProjectVRM. I knew it needed technologists. Not just to develop code, but to fully understand the challenges and opportunities that call technology forth into the world.

Lately one of those technologists has stepped forward and written the best VRM post I’ve ever read, including all of my own. It’s by T.Rob, in his blog The Odd is Silent. The title is Futurists Groundhog Day. An excerpt:

Why VRM?

VRM, or Vendor Relationship Management, is a new approach to conducting business in which the missing physical constraints have been replaced by technological and policy constraints that restore the balance of power between individuals and their vendors, and perhaps to some extent also their governments.

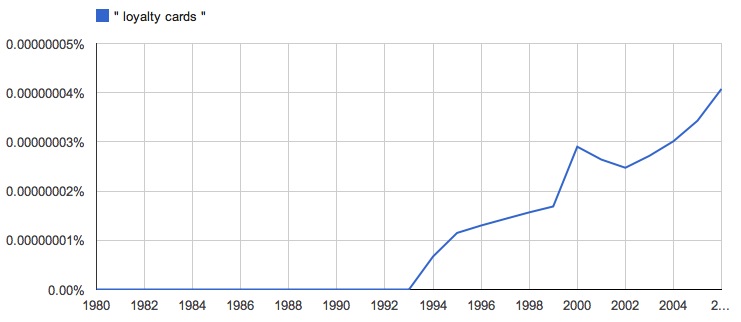

One of the issues is asymmetry in the cost of data collection. Vendors spread the capital cost of data collection over a large population of customers. Given enough time, the cost of data collection drops to near-zero or in some cases actually generates returns. Consumers on the other hand have no such infrastructure. You are co-owner of your transactional data but your grocer records each line item of your purchase in real time and you get a cryptic paper receipt which you have the option to transcribe into a database. If you had a database. And knew how to program.

VRM proposes to provide that platform so that individuals will have the means to capture more of their own data at a cost that is competitive with their vendors. Indeed, the vision is that the vendors who already have that data will some day participate in the VRM ecosystem by sharing it with their customers, in real time and full resolution. Instead of just a crappy paper receipt with unreadable abbreviated names, you’ll get the actual line items with UPC codes, prices and for some products possibly even the cradle-to-grave history and status. You’d get your smart meter readings in real time so that you could program home automation behaviors based on load, utility rate, occupancy and so forth. When you purchase online, the terms of the contract, price and all other metadata about the purchase would either be captured by you or delivered to you in real time by the vendor.

But VRM is about a lot more than just replacing today’s functionality. Just as electric motors transcended the function occupied by stem engines, VRM enables entirely new capabilities. Many are yet to be discovered but a key new capability is intentcasting. This is a direct signal from the individual to the market about preferences, requirements and purchase intent.

Read the whole thing.