On the ProjectVRM list the conversation has once again drifted to identity.

Nearly all conversation about identity in development circles around stuff Devon Loffreto of Noizivy calls administrative. It’s a good term. That’s what we get from every card some company, school or government agency prints with our name on it and we stick in our wallet. It’s what we also get from “social” login shortcuts such as Facebook’s and Twitter’s.

Regardless of the conveniences these administrative things bestow on us, what they provide is not our true identity. It might be one we use, but it is not imbued with our fully human essence, which Devon calls sovereign. In Recalibrating Sovereignty he makes a strong connection between that personal essence and what we write large (in the U.S. at least) as a nation-state of free people. Or that’s the idea anyway.

I don’t see this as a Libertarian thing (though I am sure Libertarians will find it agreeable). I see it as an elementary expression of what makes us most human: our individuality. This is not in conflict with what also makes us social, or the social nature of political, cultural, economic, educational and other institutions. Rather it enriches all of them. Saying that each of us is sovereign goes deeper than saying each of us is unique. Because we are not merely different. Each of us brings our own genius into the world. (Read John Taylor Gatto on genius, which he considers “common as dirt.”) Even genetically identical twins possess profoundly individual souls. That individuality is at the core of identity.

Right now I’m reading Orson Scott Card‘s Tales of Alvin Maker. By the fourth book Alvin’s surname has changed from Miller (what Alvin’s father was) to Smith (what Alvin was trained to be) to Maker (what Alvin becomes), each one expressing his role in the world. The name Maker identifies Alvin’s sovereign nature — one that transcends the identifier and is rooted in his nature as a sovereign soul. (The Tales are set in an early stage of American history in which this kind of choice was a common one. Check your own surname for evidence of what some ancestor did for a living. Searls, as I understand it, is a variation of Searle, which likely descends from Serlo, a Germanic or Norman word for soldier.)

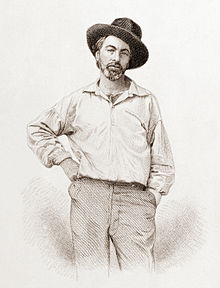

From slightly later than Alvin’s time comes Walt Whitman, the great American poet, and a tireless advocate of personal sovereignty — though I’m not aware that he ever put those two words together. Rather than explain Whitman, I’ll compress further the abridged Song of Myself that put up on the Web more than seventeen years ago:

I know I am solid and sound.

To me the converging objects of the universe

perpetually flow.

All are written to me,

and I must get what the writing means.

I know I am deathless.

I know this orbit of mine cannot be swept

by a carpenter’s compass,I know that I am august,

I do not trouble my spirit to vindicate itself

or be understood.

I see that the elementary laws never apologize.I exist as I am, that is enough.

If no other in the world be aware I sit content.

And if each and all be aware I sit content.One world is aware, and by far the largest to me,

and that is myself.

And whether I come to my own today

or in ten thousand or ten million years,

I cheerfully take it now,

or with equal cheerfulness I can wait.My foothold is tenoned and mortised in granite.

I laugh at what you call dissolution,

And I know the amplitude of time.I speak the password primeval.

I give the sign of democracy.

By God, I will accept nothing which all cannot have

their counterpart on the same terms.Encompass worlds but never try to encompass me.

I crowd your noisiest talk by looking toward you.It is time to explain myself. Let us stand up.

I am an acme of things accomplished,

and I an encloser of things to be.

Rise after rise bow the phantoms behind me.

Afar down I see the huge first Nothing,

the vapor from the nostrils of death.

I know I was even there.

I waited unseen and always.

And slept while God carried me

through the lethargic mist.

And took my time.Long I was hugged close. Long and long.

Infinite have been the preparations for me.

Faithful and friendly the arms that have helped me.Cycles ferried my cradle, rowing and rowing

like cheerful boatmen;

For room to me stars kept aside in their own rings.

They sent influences to look after what was to hold me.Before I was born out of my mother

generations guided me.

My embryo has never been torpid.

Nothing could overlay it.

For it the nebula cohered to an orb.

The long slow strata piled to rest it on.

Vast vegetables gave it substance.

Monstrous animals transported it in their mouths

and deposited it with care.All forces have been steadily employed

to complete and delight me.

Now I stand on this spot with my soul.I know that I have the best of time and space.

And that I was never measured, and never will be measured.I tramp a perpetual journey.

My signs are a rainproof coat, good shoes

and a staff cut from the wood.Each man and woman of you I lead upon a knoll.

My left hand hooks you about the waist,

My right hand points to landscapes and continents,

and a plain public road.Not I, nor any one else can travel that road for you.

You must travel it for yourself.It is not far. It is within reach.

Perhaps you have been on it since you were born

and did not know.

Perhaps it is everywhere on water and on land.Shoulder your duds, and I will mine,

and let us hasten forth.If you tire, give me both burdens and rest the chuff of your hand on my hip.

And in due time you shall repay the same service to me.Long enough have you dreamed contemptible dreams.

Now I wash the gum from your eyes.

You must habit yourself to the dazzle of the light and of every moment of your life.Long have you timidly waited,

holding a plank by the shore.

Now I will you to be a bold swimmer,

To jump off in the midst of the sea, and rise again,

and nod to me and shout,

and laughingly dash your hair.I am the teacher of athletes.

He that by me spreads a wider breast than my own

proves the width of my own.

He most honors my style

who learns under it to destroy the teacher.Do I contradict myself?

Very well then. I contradict myself.

I am large. I contain multitudes.The spotted hawk swoops by and accuses me.

He complains of my gab and my loitering.

I too am not a bit tamed. I too am untranslatable.

I sound my barbaric yawp over the roofs of the world.

No administrative entity can make that barbaric yawp.

I don’t yet know how to create a Whitman-compliant identity system (or, whatever); though my hope persists that there is already one or more in the world. Should somebody produce that system (or whatever), I’ll gladly give them SpottedHawk.com, which I’ve held for many years (with other suffixes as well), waiting like Whitman:

The last scud of day holds back for me.

It flings my likeness after the rest and true as any

on the shadowed wilds,

It coaxes me to the vapor and the desk.I depart as air.

I shake my white locks at the runaway sun.

I effuse my flesh in eddies and drift in lacy jags.I bequeath myself to the dirt and grow

from the grass I love.

If you want me again look for me under your boot soles.You will hardly know who I am or what I mean.

But I shall be good health to you nevertheless.

And filtre and fiber your blood.Failing to fetch me at first keep encouraged.

Missing me one place search another

I stop some where waiting for you.

The impact of computing on the worldwide economy, and even on business, was subject to debate until it got personal around the turn of the ’80s. Same with networking before the Internet came along in the mid ’90s.

The impact of computing on the worldwide economy, and even on business, was subject to debate until it got personal around the turn of the ’80s. Same with networking before the Internet came along in the mid ’90s.