Staples likes to make things easy.  Or so their button says.

Or so their button says.

But rebates in general are hard — on both the store and the customer. And at that Staples is no exception.

For example, yesterday at a Staples store I bought a couple reams of Staples paper for our printer. I probably would have bought the Staples brand anyway, simply because it’s cheaper. But I also couldn’t ignore the after-rebate price: $1.50 less for each ream, or $3.00 total. So I asked at the cash register if what I paid included the rebate. No, I was told. The rebate is in the electronic receipt I’d get by email. I could send in for the rebate online after getting the email.

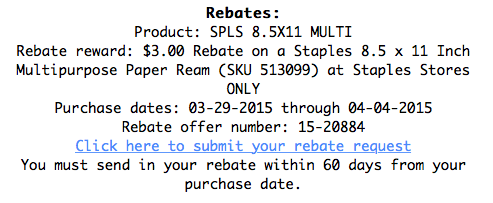

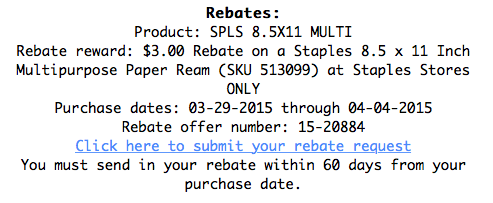

When I got home the receipt was waiting in my email inbox. Among many other promotions in the email, it said this about my rebate:

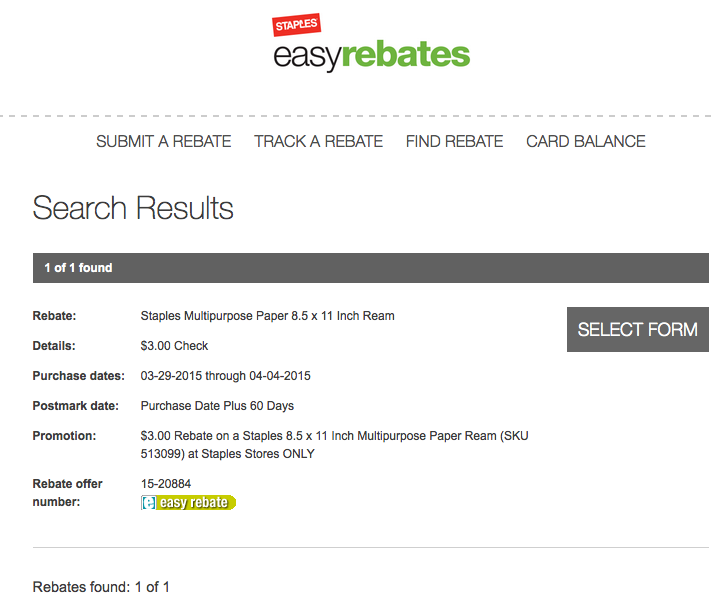

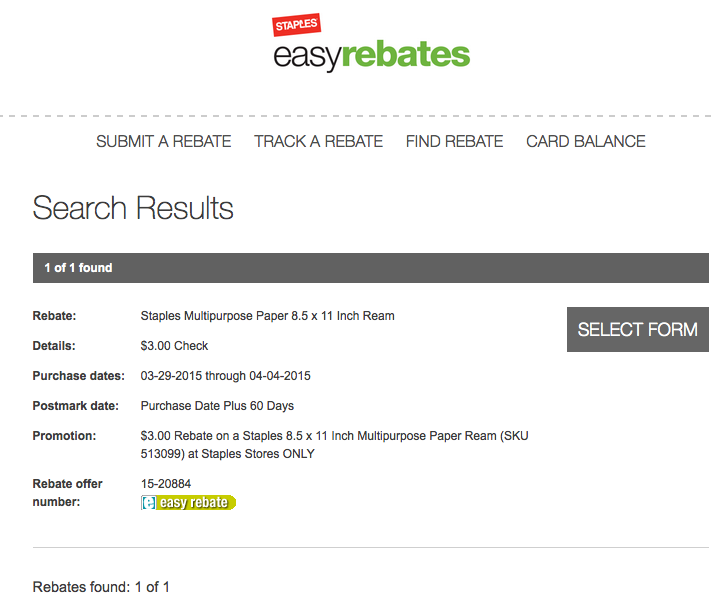

When I clicked on the link I got to this:

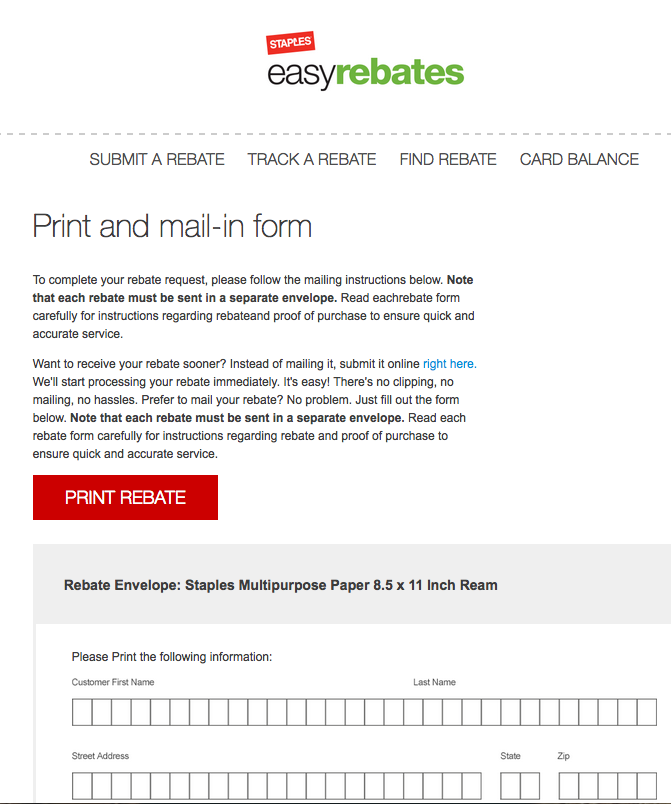

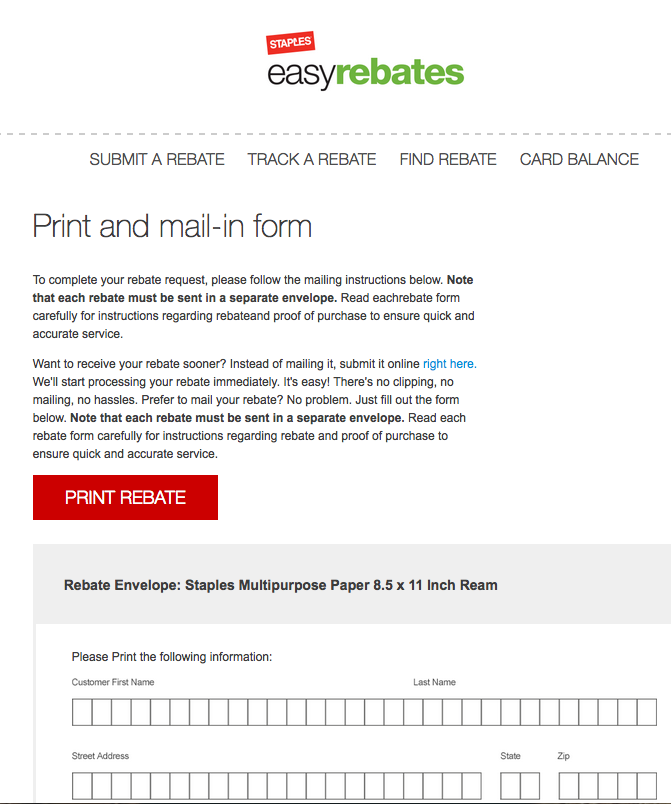

When I clicked on “SELECT FORM” I got this:

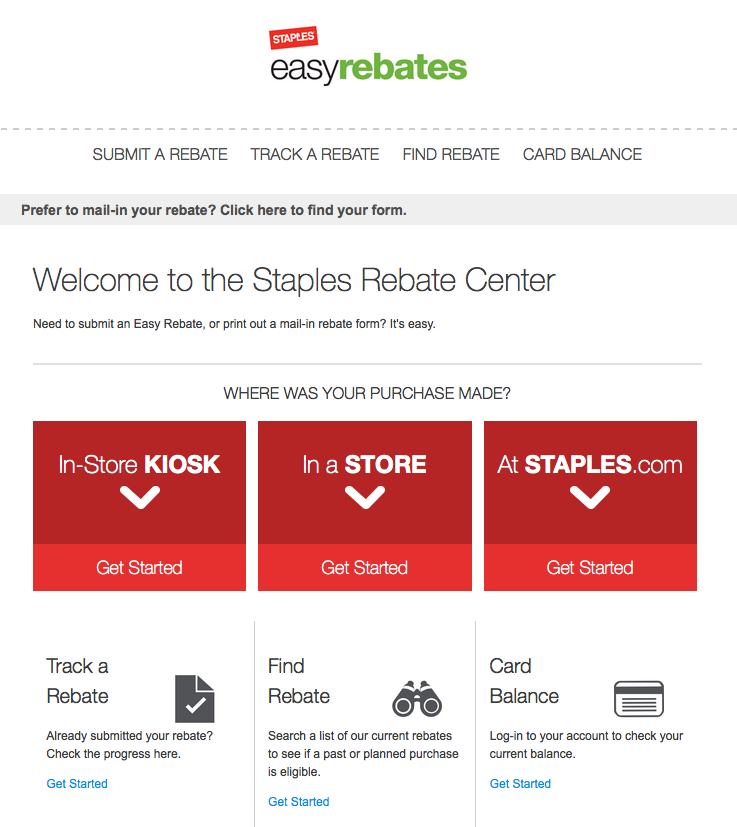

For $3, fulling out something like that, and mailing it in, is worse than a waste. So I clicked on the “right here” link, which led me here:

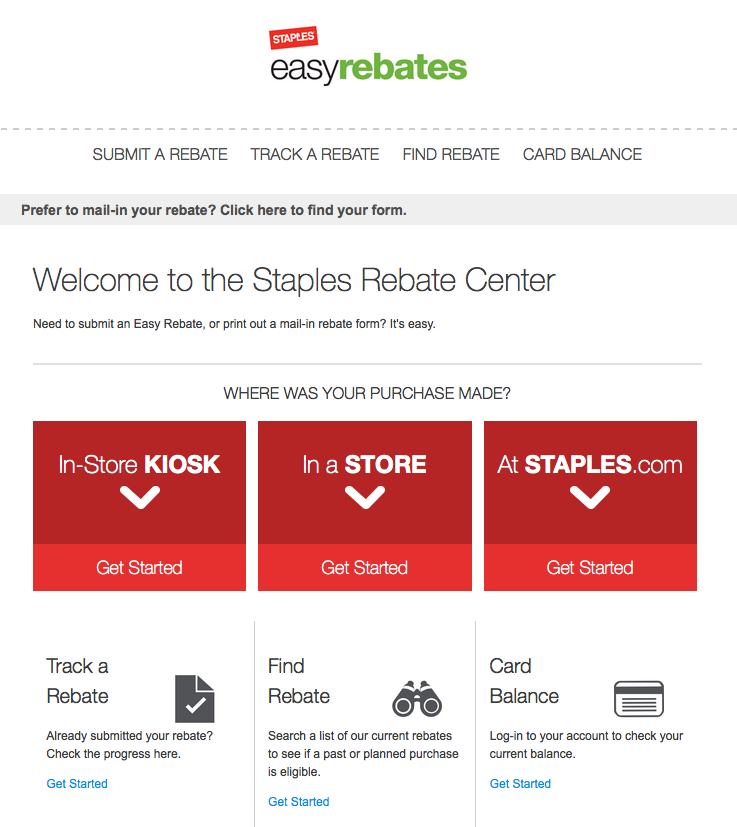

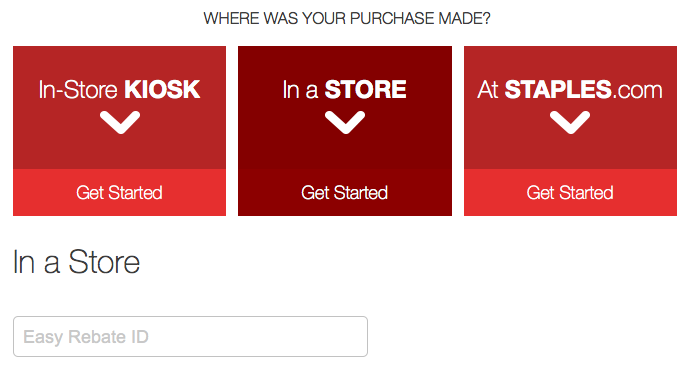

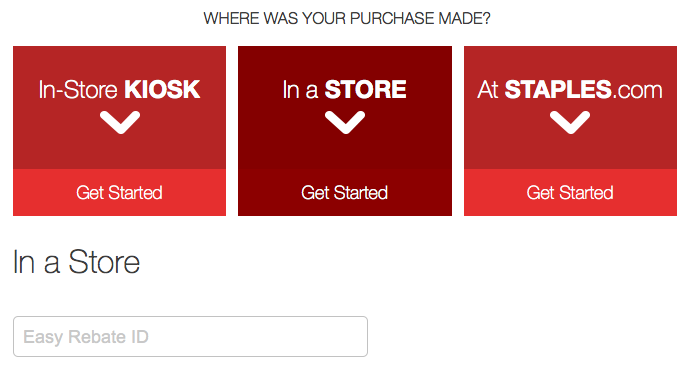

So I clicked on the center one. That got me here:

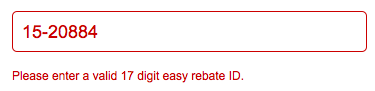

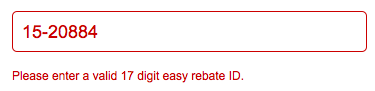

So: what was the Easy Rebate ID? All I saw, so far, was a “Rebate offer number,” on the email and back at the page that the email link brought up. So I entered it in the form and hit “NEXT.” That got me this:

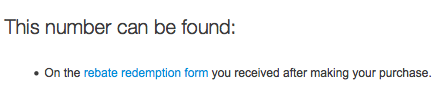

After going “Hmmm… ” I scrolled down and saw this:

Sure enough, at the bottom of the very long email with the rebate jive on it, was this:

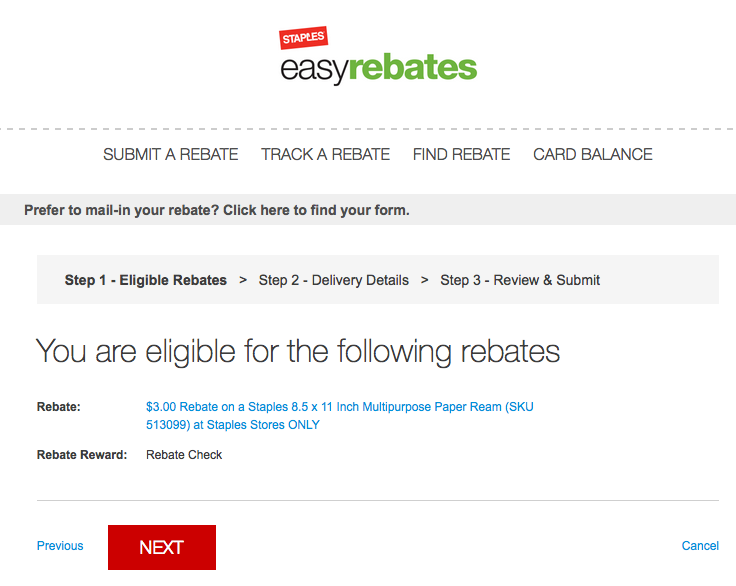

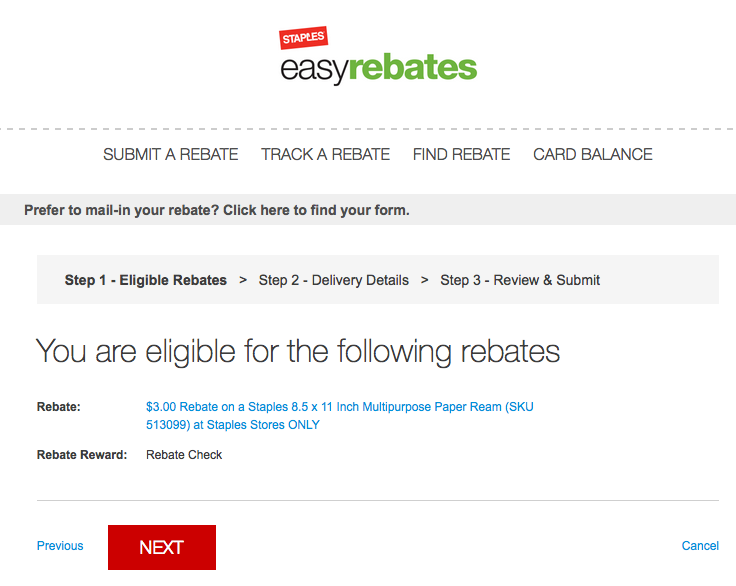

I entered that number, and it worked. Hitting “NEXT” then took me here:

When I clicked on NEXT again, I got to a page where I could register for a rebate account (by filling out a form that mined way too much personal information) or sign in. I have a Staples loyalty account; so, hoping that this might also be the rebate account, I hit “Sign in.”

I would show you the page this went to, if I could have copied it. But I couldn’t. The page had the same “Staples Easy Rebates” header, and under it just two words: “Error occurred.” When I paged down to see if there was more, the page disappeared and I was delivered back to Square Zero: the “Welcome to the Staples Rebate Center” page.

Since everything I already entered was lost, and I had no faith that entering it again would yield a different result, I gave up.

In retail parlance, this is called “breakage.” Within rebate systems, some level of breakage is a virtue. You (the retailer) don’t want everybody getting a rebate. You want as few people as possible asking for the rebate, and as few as possible succeeding at navigating an intentionally complicated series of required steps for getting the rebate. Most customers know this, of course, but every once in awhile some of us want to see if we get lucky.

This is not a good “customer experience.”In what marketers love to call “the customer journey,” it’s a wasteful and annoying side trip to an outer circle of retail hell.

So here’s a message from one customer to every retailer running a rebate program:

Any system that rationalizes breakage as a virtue is broken itself, for the simple reason that it pisses off customers. And if you want to piss off any percentage of customers — even good ones — some of the time, your whole store is broken.

So here’s a bottom line I invite Staples to consider:

Rebates save money if your time has no value. This principle applies equally to customers and companies offering rebates.

As a loyal customer of Staples — a company I’ve always liked (partly because of the “easy” promise, which they’ve been making for many years — my advice is to calculate all the overhead involved in all the promotional gimmickry used to drive sales and “loyalty” that isn’t. Include time wasted at the cash register every time the employee has to ask for a loyalty card or a phone number to recover the customer’s account, and to explain how a rebate works, plus other extraneous bullshit that has that takes time and incurs labor costs for purposes that have nothing to do with why the customer is standing at the checkout counter, just wanting to pay for goods and get the hell out of the store. Also include the inconvenience to the customer of having to carry around a card, and the corresponding administrative overhead required to manage all this complicated work, and the computing and network technology required to sustain it (and how that gets broken too). Multiply those by all the employees and customers inconvenienced by it. Then add all of it up. Be real about what percentage of your total overhead it accounts for. Remember to include the real costs to customer loyalty of pissing some of them off on purpose.

Then kill the whole thing and subtract the savings from the prices of the goods in the store. Publicize it. Hey, hold a public execution of all the added-up costs to company and customers. Talk about it as real savings, which it is. Publish papers and place editorials explaining why you’re done with the game of kidding yourselves and your customers. I know plenty of good PR firms that would be glad to help you out with this — and maybe even cut you a deal, because they’re tired of bullshitting too.

In Silicon Valley they call this “disruption.” It’s a great way to stand out, and to reposition both Staples and all of retailing.

And your customers will love it.

Don’t trust me on this. Trust Trader Joe’s. They don’t have a loyalty program, rebates or any other gimmicks. They never have discount prices. They don’t keep any data on any customers, because they don’t want the overhead, or to complicate anybody’s life. Their marketing research — no kidding — consists of this: talking to customers. That’s it. And what’s the result? Customers love them.*

Now you might say, “Yes, but Trader Joe’s is a special case. So are companies like Apple — another company customers seem to love. They only sell their own private label goods. They don’t operate in the world of co-op advertising, dealer premiums, display allowances, buyback allowances, push money, spiffs, forward buying, variable trade spending and trade deals, manufacturer coupons and all the other variables that retailers like Staples, which carry goods from hundreds of different suppliers, need to deal with constantly. And what about customers constantly hunting bargains, and comparison shopping? They want deals, and we have to compete for them.”

Sure. But why make it more complicated than it has to be?

If you really want to make things easy, for yourself and your customers, kill the bullshit. Be the no-bullshit company. Nothing would make you stand out more.

Nothing is easier, for everybody in retailing, than no bullshit at all. Or more rewarding, because customers appreciate absent bullshit at least as much as they appreciate present bargains. Especially bargains that come with labor costs — for them.

Source: The Intention Economy, pp. 223-228.

In

In