Cross-posted from Customer Commons

Some questions:

- Why do you always have to accept websites’ terms? And why do you have no record of your own of what you accepted, or when‚ or anything?

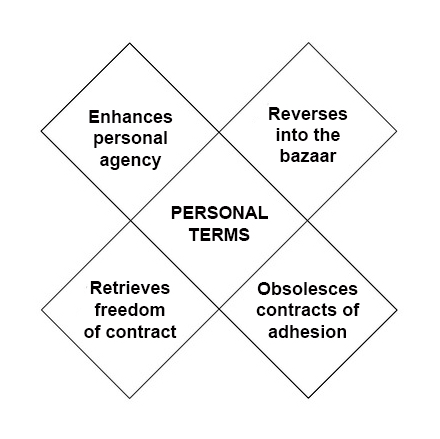

- Why do you have no way to proffer your own terms, to which websites can agree?

- Why did Do Not Track, which was never more than a polite request not to be tracked off a website, get no respect from 99.x% of the world’s websites? And how the hell did Do Not Track turn into the Tracking Preference Expression at the W2C, where the standard never did get fully baked?

- Why, after Do Not Track failed, did hundreds of millions—or perhaps billions—of people start blocking ads, tracking or both, on the Web, amounting to the biggest boycott in world history? And then why did the advertising world, including nearly all advertisers, their agents, and their dependents in publishing, treat this as a problem rather than a clear and gigantic message from the marketplace?

- Why are the choices presented to you by websites called your choices, when all those choices are provided by them? And why don’t you give them choices?

- Why does the GDPR call people mere “data subjects,” and assign the roles “data controller” and “data processor” only to other parties?* And why are nearly all the 200+million results in a search for GDPR+compliance about how companies can obey the letter of the law while violating its spirit (by continuing to track people)?

- Why does the CCPA give you the right to ask to have back personal data others have gathered about you on the Web, rather than forbid its collection in the first place? (Imagine a law that assumes that all farmers’ horses are gone from their barns, but gives those farmers a right to demand horses back from those who took them. It’s kinda like that.)

- Why, 22 years after The Cluetrain Manifesto said, we are not seats or eyeballs or end users or consumers. we are human beings and our reach exceeds your grasp. deal with it. —is that statement still not true?

- Why, 9 years after Harvard Business Review Press published The Intention Economy: When Customers Take Charge, has that not happened? (Really, what are you in charge of in the marketplace that isn’t inside companies’ silos and platforms?)

The easiest answer to all of those is the cookie. Partly because without it none of those questions would be asked, and partly because it’s at the center of attention for everyone who cares today about the issues involved in those quesions.

The idea behind the cookie (way back in 1994, when Lou Montulli thought it up) was for a site to remember its visitors by planting reminder files—cookies—in visitors’ browsers. That would make it easy for site visitors to pick up where they left off when they arrived back. It was an innocent idea at the time; but it reified a construct: one that has permanently subordinated visitors to websites.

And it has thus far proven impossible to change that construct. It is, alas, the way the Web works.

Hey, maybe we can still change it. But why bother when there should be any number of other ways for demand and supply to signal each other in a networked marketplace? Better ways: ones that don’t depend on sites, search engines, social media and other parties inferring, mostly through surveillance, what might be “relevant” or “interest-based” for the individual? Ones that give individuals full agency and signaling power?

So we’d like to introduce one. It’s called the Intention Byway. It’s the brain-baby of our CTO, Hadrian Zbarcea, and it is informed by his ample experience with the Apache Software Foundation, SWIFT, the FAA and other enterprises large and small.

In this model, the byway is the path along which messages signaling intent travel between individuals and companies (or anyone), each of which has a simple computer called an intentron, which sends and receives those messages, and also executes code for the owner’s purposes as a participant in the open marketplace the Internet was designed to support.

As computers (which can be physical or virtual), intentrons run apps that can come from any source in the free and open marketplace, and not just from app stores of controlling giants such as Apple and Google. These apps can run algorithms that belong to you, and can make useful sense of your own data. (For example, data about finances, health, fitness, property, purchase history, subscriptions, contacts, calendar entries—all those things that are currently silo’d or ignored by silo builders that want to trap you inside their proprietary systems.) The same apps also don’t need to be large. Early prototypes have less than 100 lines of code.

Messages called intentcasts can be sent from intentrons to markets on the pub-sub model, through the byway, which is asynchronous, similar to email in the online world and package or mail forwarding in the offline world. Subscribers on the sell side will be listening for signals from markets for anything. Name a topic, and there’s something to subscribe to. Intentcasts on the customers’ side are addressed to markets by topical name. Responsibilities along the way are handled by messaging and addressing authorities. Addresses themselves are URNs, or Uniform Resource Names.

These are some businesses that can thrive along the Intention Byway:

- Intentron makers

- Intentron sellers

- App makers

- App sellers (or stores)

- Addressing authorities

- Messaging authorities

- Message routers (operating like CDNs, or content distribution networks)

—in addition to sellers looking for better signals from the demand side of the market than surveillance-based guesswork can begin to equal.

We are not looking to boil an ocean here (though we do see our strategy as a blue one). The markets first energized by the promise of this model are local and vertical. Real estate in Boston and farm-to-table in Michigan are the two we featured on VRM/CuCo Day and in all three days of the Internet Identity Workshop, which all took place last week. Over the coming days and weeks, we will post details on how the Intention Byway works, starting with those two markets.

We also see the Intention Byway as complementary to, rather than competitive with, developments with similar ambitions, such as SSI, DIDcomm, picos, and JLINC. Once we take off our browser blinders, a gigantic space for new e-commerce development appears. All of those, and many more, will have work to do in it.

So stay tuned for more about life after cookies—and outside the same old bakery.

*Specifically, a “data controller” is “a legal or natural person, an agency, a public authority, or any other body who, alone or when joined with others, determines the purposes of any personal data and the means of processing it.”

While this seems to say that any one of us can be a data controller, that was not what the authors of the GDPR had in mind. They only wanted to maximize the width of the category to include solo operators, rather than to include the individual from whom personal data is collected. (Read what follows from that last link to see what I mean.) Still, this is a loophole through which personal agency can move, because (says the GDPR) the “data subject” whose rights the GDPR protects, is a “natural person.”

The

The difference between Phase One and Phase Two is

difference between Phase One and Phase Two is  Next steps in tracking protection and ad blocking. At the last VRM Day and IIW, we discussed

Next steps in tracking protection and ad blocking. At the last VRM Day and IIW, we discussed