And privacy be damned.

See, there is an iron law for every new technology: What can be done will be done. And a corollary that says, —until it’s clear what shouldn’t be done. Let’s call those Stage One and Stage Two.

With respect to safety from surveillance in our cars, we’re at Stage One.

For Exhibit A, read what Ray Schultz says in Can Radio Time Be Bought With Real-Time Bidding? iHeartMedia is Working On It:

HeartMedia hopes to offer real-time bidding for its 860+ radio stations in 160 markets, enabling media buyers to buy audio ads the way they now buy digital.

“We’re going to have the capabilities to do real-time bidding and programmatic on the broadcast side,” said Rich Bressler, president and COO of iHeart Media, during the Goldman Sachs Communacopia + Technology Conference, according to Radio Insider.

Bressler did not offer specifics or a timeline. He added: “If you look at broadcasters in general, whether they’re video or audio, I don’t think anyone else is going to have those capabilities out there.”

“The ability, whenever it comes, would include data-infused buying, programmatic trading and attribution,” the report adds.

The Trade Desk lists iHeart Media as one of its programmatic audio partners.

Audio advertising allows users to integrate their brands into their audiences’ “everyday routines in a distraction-free environment, creating a uniquely personalized ad experience around their interests,” the Trade Desk says.

The Trade Desk “specializes in real-time programmatic marketing automation technologies, products, and services, designed to personalize digital content delivery to users.” Translation: “We’re in the surveillance business.”

Never mind that there is negative demand for surveillance by the surveilled. Push-back has been going on for decades. Here are 154 pieces I’ve written on the topic since 2008.

One might think radio is ill-suited for surveillance because it’s an offline medium. Peopler listen more to actual radios than to computers or phones. Yes, some listening is online; but not much, relatively speaking. For example, here is the bottom of the current radio ratings for the San Francisco market:

Those numbers are fractions of one percent of total listening in the country’s most streaming-oriented market.

So how are iHeart and The Trade Desk going to personalize radio ads? Well, here is a meaningful excerpt from iHeart To Offer Real-Time Bidding For Its Broadcast Ad Inventory, which ran earlier this month at Inside Radio:

The biggest challenge at iHeartMedia isn’t attracting new listeners, it’s doing a better job monetizing the sprawling audience it already has. As part of ongoing efforts to sell advertising the way marketers want to transact, it now plans to bring real-time bidding to its 850 broadcast radio stations, top company management said Thursday.

“We’re going to have the capabilities to do real-time bidding and programmatic on the broadcast side,” President and COO Rich Bressler said during an appearance at the Goldman Sachs Communacopia + Technology Conference. “If you look at broadcasters in general, whether they’re video or audio, I don’t think anyone else is going to have those capabilities out there.”

Real-time bidding is a subcategory of programmatic media buying in which ads are bought and sold in real time on a per-impression basis in an instant auction. Pittman and Bressler didn’t offer specifics on how this would be accomplished other than to say the company is currently building out the technology as part of a multi-year effort to allow advertisers to buy iHeart inventory the way they buy digital media advertising. That involves data-infused buying and programmatic trading, along with ad targeting and campaign attribution.

Radio’s largest group has also moved away from selling based on rating points to transacting on audience impressions, and migrated from traditional demographics to audiences or cohorts. It now offers advertisers 800 different prepopulated audience segments, ranging from auto intenders to moms that had a baby in the last six months…

Advertisers buy iHeart’s ad inventory “in pieces,” Pittman explained, leaving “holes in between” that go unsold. “Digital-like buying for broadcast radio is the key to filling in those holes,” he added…

…there has been no degradation in the reach of broadcast radio. The degradation has been in a lot of other media, but not radio. And the reason is because what we do is fundamentally more important than it’s ever been: we keep people company.”

Buried in that rah-rah is a plan to spy on people in their cars. Because surveillance systems are built into every new car sold. In Privacy Nightmare on Wheels’: Every Car Brand Reviewed By Mozilla — Including Ford, Volkswagen and Toyota — Flunks Privacy Test, Mozilla pulls together a mountain of findings about just how much modern cars spy on their drivers and passengers, and then pass personal information on to many other parties. Here is one relevant screen grab:

As for consent? When you’re using a browser or an app, you’re on the global Internet, where the GDPR, the CCPA, and other privacy laws apply, meaning that websites and apps have to make a show of requiring consent to what you don’t want. But cars have no UI for that. All their computing is behind the dashboard where you can’t see it and can’t control it. So the car makers can go nuts gathering fuck-all, while you’re almost completely in the dark about having your clueless ass sorted into one or more of Bob Pittman’s 800 target categories. Or worse, typified personally as a category of one.

Of course, the car makers won’t cop to any of this. On the contrary, they’ll pretend they are clean as can be. Here is how Mozilla describes the situation:

Many car brands engage in “privacy washing.” Privacy washing is the act of pretending to protect consumers’ privacy while not actually doing so — and many brands are guilty of this. For example, several have signed on to the automotive Consumer Privacy Protection Principles. But these principles are nonbinding and created by the automakers themselves. Further, signatories don’t even follow their own principles, like Data Minimization (i.e. collecting only the data that is needed).

Meaningful consent is nonexistent. Often, “consent” to collect personal data is presumed by simply being a passenger in the car. For example, Subaru states that by being a passenger, you are considered a user — and by being a user, you have consented to their privacy policy. Several car brands also note that it is a driver’s responsibility to tell passengers about the vehicle’s privacy policies.

Autos’ privacy policies and processes are especially bad. Legible privacy policies are uncommon, but they’re exceptionally rare in the automotive industry. Brands like Audi and Tesla feature policies that are confusing, lengthy, and vague. Some brands have more than five different privacy policy documents, an unreasonable number for consumers to engage with; Toyota has 12. Meanwhile, it’s difficult to find a contact with whom to discuss privacy concerns. Indeed, 12 companies representing 20 car brands didn’t even respond to emails from Mozilla researchers.

And, “Nineteen (76%) of the car companies we looked at say they can sell your personal data.”

To iHeart? Why not? They’re in the market.

And, of course, you are not.

Hell, you have access to none of that data. There’s what the dashboard tells you, and that’s it.

As for advice? For now, all I have is this: buy an old car.

The

The difference between Phase One and Phase Two is

difference between Phase One and Phase Two is  Next steps in tracking protection and ad blocking. At the last VRM Day and IIW, we discussed

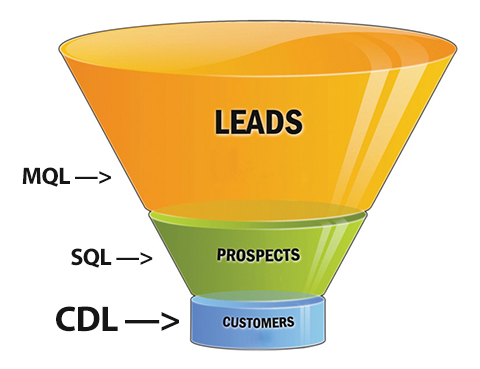

Next steps in tracking protection and ad blocking. At the last VRM Day and IIW, we discussed  Imagine customers diving, on their own, straight down to the bottom of the sales funnel.

Imagine customers diving, on their own, straight down to the bottom of the sales funnel.