Prompt: “A public marketplace for digital goods where people pay whatever they please for everything they consume.” Via Microsoft Image Creator

Now that we’ve hit peak subscription, and paywalls are showing up in front of formerly free digital goods (requiring, of course, more subscriptions), perhaps the world is ready for EmanciPay, an idea that has been biding its time on our wiki since 2009.

So, rather than leave it buried there, we’ll surface it here. Dig:::

Overview

Simply put, Emancipay makes it easy for anybody to pay (or offer to pay) —

- as much as they like

- however they like

- for whatever they like

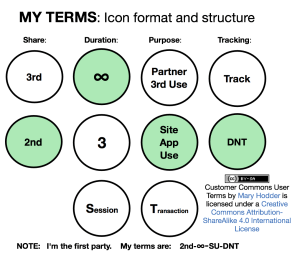

- on their own terms

— or at least to start with that full set of options, and to work out differences with sellers easily and with minimal friction.

Emancipay turns consumers (aka users) into customers by giving them a pricing gun (something which in the past only sellers used) and their own means to make offers, to pay outright, and to escrow the intention to pay when price and other requirements are met. And to be able to do this at scale across all sellers, much as cash, browsers, credit cards, and email clients do the same. Payments themselves can also be escrowed.

In slightly more technical terms, EmanciPay is a payment framework for customers operating with full agency in the open marketplace, and at scale. It operates on open protocols and standards, so it can be used by any buyer, seller or intermediary.

It was conceived as a way to pay for music, journalism, or what any artist brings into the world. But it can apply to anything. For example, [subscriptions], have become a giant fecosystem in which every seller has separate and non-substitutable scale across all subscribers, while subscribers have zero scale across all sellers, with the highly conditional exceptions of silo’d commercial intermediaries. As [Customer Commons] puts it,

There’s also not much help coming from the subscription management services we have on our side: Truebill, Bobby, Money Dashboard, Mint, Subscript Me, BillTracker Pro, Trim, Subby, Card Due, Sift, SubMan, and Subscript Me. Nor from the subscription management systems offered by Paypal, Amazon, Apple or Google (e.g. with Google Sheets and Google Doc templates). All of them are too narrow, too closed and exclusive, too exposed to the surveillance imperatives of corporate giants, and too vested in the status quo.

That status quo sucks (see here, or just look up “subscription hell”), and it’s way past time to unscrew it.) But how?

The better question is where?

The answer to that is on our side: the customer’s side.

While EmanciPay was first conceived by ProjectVRM as a way to make live payments to nonprofits and to provide a new monetization method for publishers. it also works as a counterpart to sellers’ subscription systems in what Zuora (a supplier of subscription management systems to the publishing industry, including The Guardian and Financial Times) calls the “subscription economy“, which it says “is built on ever-changing relationships with your customers”. Since relationships are two-way by nature, EmanciPay is one way that customers can manage their end, while publisher-side systems such as Zuora’s manage the other.

Emancipay economic case

EmanciPay provides a new form of economic signaling not available to individuals, either on the Net or before the Net became available as a communications medium. EmanciPay will use open standards and be comprised of open-source code. While any commercial fourth parties can use EmanciPay (or its principles, or any parts of it they like), EmanciPay’s open and standard framework will support fourth parties by making them substitutable, much as the open standards of email (SMTP, POP3, IMAP) make email systems substitutable. (Each has what Joe Andrieu calls service endpoint portability.)

EmanciPay is an instrument of customer independence from all of the billion (or so) commercial entities on the Net, each with its own arcane and siloed systems for engaging and managing customer relations, as well as receipt, acknowledgment, and accounting for payments from customers.

Use Case Background

EmanciPay was conceived originally as a way to provide customers with the means to signal interest and the ability to pay for media and creative works (most of which are freely available on the Web, if not always free of charge). Through EmanciPay, demand and supply can relate, converse, and transact business on mutually beneficial terms, rather than only on terms provided by the countless different siloed systems we have today, each serving to hold the customer captive, and causing much inconvenience and friction in the process.

Media goods were chosen for five reasons: 1) because most are available for free, even if they cost money, or are behind paywalls 2) paywalls, which are cookie-based, cannot relate to individuals as anything other than submissive and dependent parties (and each browser a users employs carries a different set of cookies) 3) both media companies and non-profits are constantly looking for new sources of revenue 4) the subscription model, while it creates steady income and other conveniences for sellers, is often a bad deal for customers, and is now so overused (see Subscriptification) that the world is approaching a peak subscription crisis, and unscrewing it can only happen from the customer’s side (because the business is incapable of unscrewing the problem itself 5) all methods of intermediating payment choices are either siloed by the seller or siloed by intermediators, discouraging participation by individuals.

What the marketplace requires are new business and social contracts that ease payment and stigmatize non-payment for creative goods. The friction involved in voluntary payment is still high, even on the Web, where one must go through complex ceremonies even to make simple payments. There is no common and easy way either to keep track of what media (free or otherwise) we use (see Media Logging), to determine what it might be worth, and to pay for it easily and in standard ways — to many different suppliers. (Again, each supplier has its own system for accepting payments.)

EmanciPay differs from other payment models (subscriptions, newsstands, tip jars) by providing customers with the ability to choose what they wish to pay and how they’ll pay it, with minimum friction — and with full choice about what they disclose about themselves.

EmanciPay will also support credit for referrals, requests for service, feedback, and other relationship support mechanisms, all at the control of the user. For example, EmanciPay can provide quick and easy ways for listeners to pay for public radio broadcasts or podcasts, for readers to pay for otherwise “free” papers or blogs, for listeners to pay to hear music and support artists, for users to issue promises of payment for stories or programs — all without requiring the individual to disclose unnecessary private information or to become a “member” — although these options are kept open.

This will scaffold genuine relationships between buyers and sellers in the media marketplace. It will also give deeper meaning to “membership” in non-profits. (Under the current system, “membership” generally means putting one’s name on a pitch list for future contributions, and not much more than that.)

EmanciPay will also connect the sellers’ CRM (Customer Relationship Management) systems with customers’ VRM (Vendor Relationship Management) systems, supporting rich and participatory two-way relationships. In fact, EmanciPay will by definition be a VRM system.

Micro-accounting and Macro-distribution

The idea of “micro-payments” for goods on the Net has been around for a long time and is often brought up as a potential business model for journalism. For example in this article by Walter Isaacson in Time Magazine. It hasn’t happened, at least not globally, because it’s too complicated, and in prototype only works inside private silos.

What ProjectVRM suggests instead is something we don’t yet have, but very much need:

- micro-accounting for actual uses. Think of this simply as “keeping track of” the news, podcasts, newsletters, or music we consume.

- macro-distribution of payments for accumulated use (that’s no longer “micro”).

Much — maybe most — of the digital goods we consume are both free for the taking and worth more than $zero. How much more? We need to be able to say. In economic terms, demand needs to have a much wider range of signals it can give to supply. And give to each other, to better gauge what we should be willing to pay for free stuff that has real value but not a hard price.

As currently planned, EmanciPay would –

- Provide a single and easy way for consumers of “content” to become customers of it. In the current system — which isn’t one — every artist, every musical group, and every public radio and TV station has his, her or own way of taking in contributions from those who appreciate the work. This can be arduous and time-consuming for everybody involved. (Imagine trying to pay separately every musical artist you like, for all your enjoyment of each artist’s work.) What EmanciPay proposes, however, is not a replacement for existing systems, but a new system that can supplement existing fund-raising systems — one that can soak up much of today’s MLOTT: Money Left On The Table.

- Provide ways for individuals to look back through their media usage histories, inform themselves about what they have been enjoying, and determine how much it is worth to them. The Copyright Arbitration Royalty Panel (CARP), and later the Copyright Royalty Board (CRB), both came up with “rates and terms that would have been negotiated in the marketplace between a willing buyer and a willing seller.” This almost absurd language first appeared in the 1995 Digital Performance Royalty Act (DPRA) and was tweaked in 1998 by the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), under which both the CARP and the CRB operated. The rates they came up with peaked at $.0001 per “performance” (a song or recording), per listener. EmanciPay creates the “willing buyer” that the DPRA thought wouldn’t exist.

- Stigmatize non-payment for worthwhile media goods. This is where “social” will finally come to be something more than yet another tech buzzmodifier.

All these require micro-accounting, not micro-payments. Micro-accounting can inform ordinary payments that can be made in clever new ways that should satisfy everybody with an interest in seeing artists compensated fairly for their work. An individual listener, for example, can say “I want to pay 1¢ for every song I hear,” and “I’ll send SoundExchange a lump sum of all the pennies wish to pay for songs I have heard over a year, along with an accounting of what artists and songs I’ve listened to” — and leave dispersal of those totaled pennies up to the kind of agency that likes, and can be trusted, to do that kind of thing. That’s the macro-distribution part of the system.

Similar systems can also be put in place for readers of newspapers, blogs, and other journals. What’s important is that the control is in the hands of the individual and that the accounting and dispersal systems work the same way for everybody.