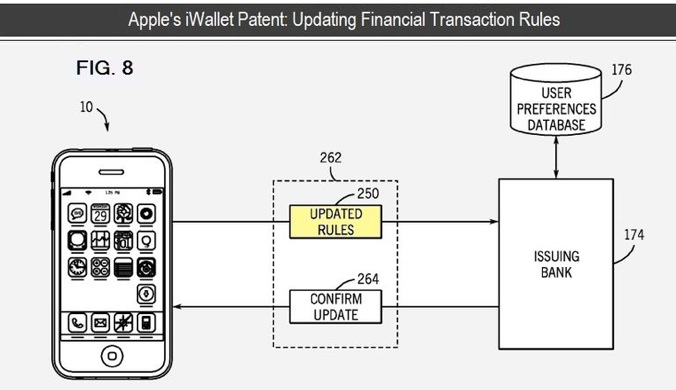

Now comes news that Apple has been granted a patent for the iWallet. Here’s one image among many at that last link:

Note the use of the term “rules.” Keep that word in mind. It is a Good Word.

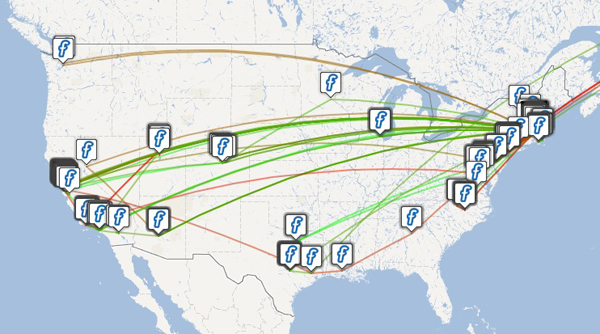

Now look at this diagram from Phil Windley‘s Event Channels post:

Another term for personal event network is personal cloud. Phil visits this in An Operating System for Your Personal Cloud, where he says, “In contrast a personal event network is like an OS for your personal cloud. You can install apps to customize it for your purpose, it canstore and manage your personal data, and it provides generalized services through APIsthat any app can take advantage of.” One of Phil’s inventions is the Kinetic Rules Language, or KRL, and the rules engine for executing those rules, in real time. Both are open source. Using KRL you (or a programmer working for you, perhaps at a fourth party working on your behalf, can write the logic for connecting many different kinds of events on the Live Web, as Phil describes here).

What matters here is that you write your own rules. It’s your life, your relationships and your data. Yes, there are many relationships, but you’re in charge of your own stuff, and your own ends of those relationships. And you operate as free, independent and sovereign human being. Not as a “user” inside a walled garden, where the closest thing you can get to a free market is “your choice of captor.”

Underneath your personal cloud is your personal data store (MyDex, et. al.), service (Higgins), locker (Locker Project / Singly), or vault (Personal.com). Doesn’t matter what you call it, as long as it’s yours, and you can move the data from one of these things into another, if you like, compliant with the principles Joe Andrieu lays out in his posts on data portability, transparency, self-hosting and service endpoint portability.

Into that personal cloud you should also be able to pull in, say, fitness data from Digifit and social data from any number of services, as Singly demonstrates in its App Gallery. One of those is Excessive Mapper, which pulls together checkins with Foursquare, Facebook and Twitter. I only check in with Foursquare, which gives me this (for the U.S. at least):

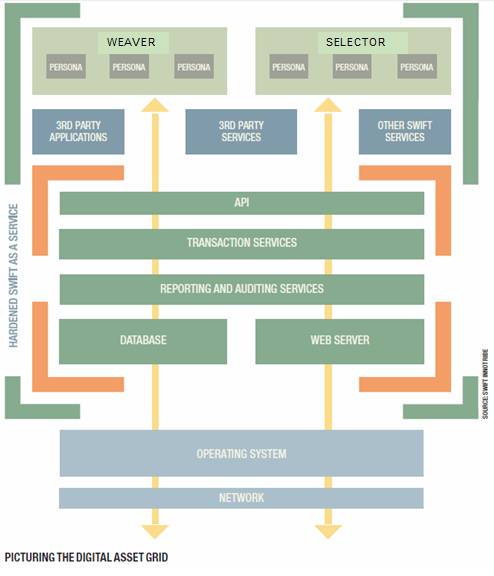

The thing is, your personal cloud should be yours, not somebody else’s. It should contain your data assets. The valuable nature of personal data is what got the World Economic Forum to consider personal data an asset class of its own. To help manage this asset class (which has enormous use value, and not just sale value), a number of us (listed by Tony Fish in his post on the matter) spec’d out the Digital Asset Grid, or DAG…

… which was developed with Peter Vander Auwera and other good folks at SWIFT (and continues to evolve).

There are more pieces than that, but I want to bring this back around to where your wallet lives, in your purse or your back pocket.

Wallets are personal. They are yours. They are not Apple’s or Google’s or Microsoft’s, or any other company’s, although they contain rectangles representing relationships with various companies and organizations:

Still, the container you carry them in — your wallet — is yours. It isn’t somebody else’s.

But it’s clear, from Apple’s iWallet patent, that they want to own a thing called a wallet that lives in your phone. Does Google Wallet intend to be the same kind of thing? One might say yes, but it’s not yet clear. When Google Wallet appeared on the development horizon last May, I wrote Google Wallet and VRM. In August, when flames rose around “real names” and Google +, I wrote Circling Around Your Wallet, expanding on some of the same points.

What I still hope is that Google will want its wallet to be as open as Android, and to differentiate their wallet from Apple’s through simple openness. But, as Dave Winer said a few days ago…

Big tech companies don’t trust users, small tech companies have no choice. This is why smaller companies, like Dropbox, tend to be forces against lock-in, and big tech companies try to lock users in.

Yet that wasn’t the idea behind Android, which is why I have a degree of hope for Google Wallet. I don’t know enough yet about Apple’s iWallet; but I think it’s a safe bet that Apple’s context will be calf-cow, the architecture I wrote about here and here. (In that architecture, you’re the calf, and Apple’s the cow.) Could also be that you will have multiple wallets and a way to unify them. In fact, that’s probably the way to bet.

So, in the meantime, we should continue working on writing our own rules for our own digital assets, building constructive infrastructure that will prove out in ways that require the digital wallet-makers to adapt rather than to control.

I also invite VRM and VRooMy developers to feed me other pieces that fit in the digital assets picture, and I’ll add them to this post.