For sixteen years, ProjectVRM has encouraged the development of tools and services that solve business problems from the customer side. This work is toward testing a theory: that free customers are more valuable—to themselves and to the businesses they engage—than captive ones. That theory can only be tested when tools for doing that are in place.

We already have some of those tools. Our big four in the digital world are the browser, the phone, email, and texting. In the analog offline world, our best model is cash. From The Cash Model of Customer Experience:

Here’s the handy thing about cash: it gives customers scale. It does that by working the same way for everybody, everywhere it’s accepted. It’s also anonymous by nature, meaning it carries no personal identifiers. Recording what happens with it is also optional, because using it doesn’t require an entry in a ledger (as happens with cryptocurrencies). Cash has also been working this way for thousands of years. But we almost never talk about our “experience” with cash, because we don’t need to.

The problem with our four personal digital tools—browser, phone, email and texting—is that they are not fully ours. So our agency is at best compromised. Specifically,

- The most popular browsers are also agents of Apple, Google, Microsoft, plus countless thousands of third parties inserting cookies and other tracking instruments into our devices.

- Our phones are not just ours. They are corporate tentacles of Apple and Google, lined with countless personal data suction cups from unknown surveillance systems. (For more on this, see Apple vs (or plus) Adtech, Part I and Part II.)

- Apple and Google together supply 87% of all email software and services. Apple promises privacy, while Google makes a business out of knowing the contents of your messages, plus every other Google-provided or -involved piece of software reveals to the company about your life. As for how well Apple delivers on its privacy promises, look up apple+compromised+privacy.

- The original messaging service for phones, SMS, is owned and run by phone companies. Other major messaging, texting and chat services are run entirely by private companies.

- Among common Internet activities, only email and browsing are based on open and simple standards. The main ones are SMTP, IMAP, and POP3 for email, and HTTP/S for browsing. Those share the Internet’s three NEA virtues: Nobody owns them, Everybody can use them, and Anybody can improve them.

This is important: If a product or service mostly works for some company, it’s not yours. You are a user or a consumer. You are not a customer; nor are you operating with full agency in a truly free market. So, while it is obvious that all of us are made more valuable to business, and to ourselves, because we use browsers, phones, email, and messaging, we can’t say that we are free while we do.

But the Internet is still young: dating in its current form—supportive of e-commerce—since 30 April 1995, when the NSFNET (one of the Internet’s backbones) was decommissioned, and its policy forbidding commercial traffic on its pipes no longer stood in the way. The Net will also be with us for dozens or hundreds of decades to come, with its base protocol, TCP/IP, continuing to support freedom for every node on it.

More importantly, there are many business problems best or only solved from the customer side. Here is a list:

- Identity. Logins and passwords are burdensome leftovers from the last millennium. There should be (and already are) better ways to identify ourselves by revealing to others only what we need them to know. Working on this challenge is the SSI—Self-Sovereign Identity—movement. (Which also goes by many other names. The latest is Web5.) The solution here for individuals is tools of their own that scale. Note that there is a LOT happening here. One good way keep up with it is in the Identisphere newsletter. You can also participate by attending the twice-yearly Internet Identity Workshop, which has been going strong since 2005.

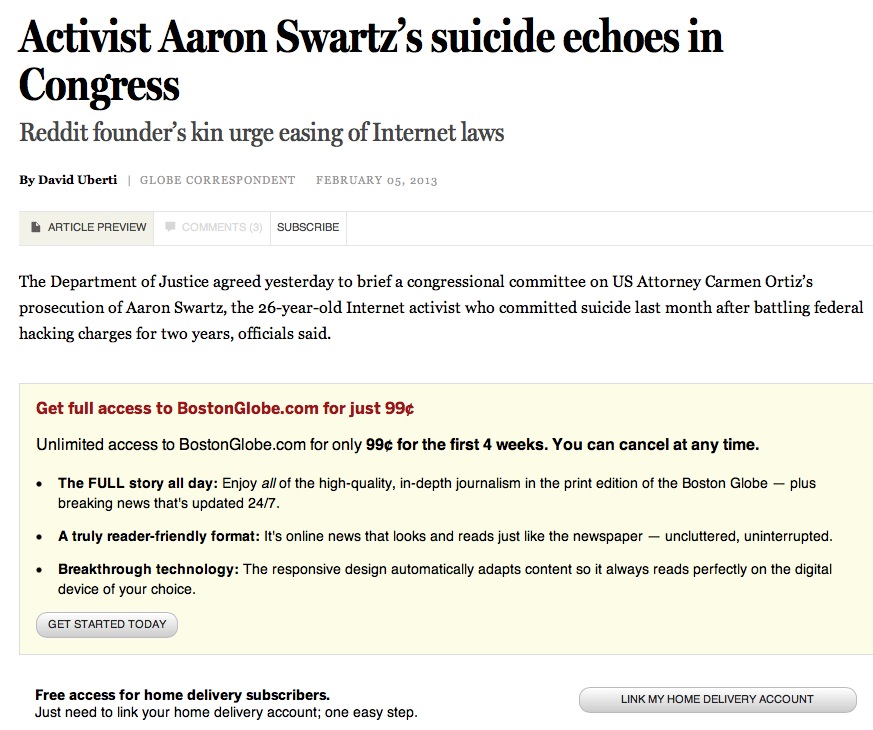

- Subscriptions. Nearly all subscriptions are pains in the butt. “Deals” can be deceiving, full of conditions and changes that come without warning. New customers often get better deals than loyal customers. And there are no standard ways for customers to keep track of when subscriptions run out, need renewal, or change. The only way this can be normalized is from the customers’ side.

- Terms and conditions. In the world today, nearly all of these are ones that companies proffer; and we have little or no choice about agreeing to them. Worse, in nearly all cases, the record of agreement is on the company’s side. Oh, and since the GDPR came along in Europe and the CCPA in California, entering a website has turned into an ordeal typically requiring “consent” to privacy violations the laws were meant to stop. Or worse, agreeing that a site or a service provider spying on us is a “legitimate interest.” The solution here is terms individuals can proffer and organizations can agree to. The first of these is #NoStalking, and allows a publisher to do all the advertising they want, so long as it’s not based on tracking people. Think of it as the opposite of an ad blocker. (Customer Commons is also involved in the IEEE’s P7012 Standard for Machine Readable Personal Privacy Terms.

- Payments. For demand and supply to be truly balanced, and for customers to operate at full agency in an open marketplace (which the Internet was designed to support), customers should have their own pricing gun: a way to signal—and actually pay willing sellers—as much as they like, however, they like, for whatever they like, on their own terms. There is already a design for that, called EmanciPay. Its promise for the music industry alone is enormous.

- Intentcasting. Advertising is all guesswork, which involves massive waste. But what if customers could safely and securely advertise what they want, and only to qualified and ready sellers? This is called intentcasting, and to some degree, it already exists. Toward this, the Intention Byway is a core focus of Customer Commons. (Also see a list of intentcasting providers on the ProjectVRM Development Work list.)

- Shopping. Why can’t you have your own shopping cart—that you can take from store to store? Because we haven’t invented one yet. But we can. And when we do, all sellers are likely to enjoy more sales than they get with the current system of all-silo’d carts.

- Internet of Things. We don’t have this yet. Instead, we have the Apple of things, the Amazon of things, the Google of things, the Samsung of things, the Sonos of things, and so on, each silo’d in separate systems we don’t control. Things we own on the Internet should be our things. We should be able to control them, as independent operators, as we do with our computers and mobile devices. (Also, by the way, things don’t need to be intelligent or connected to belong to the Internet for us to control what’s known about them. They can be, or have, picos.)

- Loyalty. All loyalty programs are gimmicks, and coercive. True loyalty is worth far more to companies than the coerced kind, and only customers are in a position to truly and fully express it. We should have our own loyalty programs, to which companies are members, rather than the reverse.

- Privacy. We’ve had privacy tech in the physical world since the inventions of clothing, shelter, locks, doors, shades, shutters, and other ways to limit what others can see or hear—and to signal to others what’s okay and what’s not. Instead, all we have are unenforced promises by others not to watch our naked selves, or to report what they see to others. Or worse, coerced urgings to “accept” spying on us and distributing harvested information about us to parties unknown, with no record of what we’ve agreed to.

- Customer service. There are no standard ways for customers and companies to enjoy relationships, with useful data flowing both ways, and for help to come when it’s needed. Instead, every company does it differently, in its own silo’d system. For more on this, see # 12 below.

- Regulatory compliance. Especially around privacy. Because really, all the GDPR and the CCPA want is for companies to stop spying on people. Without any privacy tech on the individual’s side, however, responsibility for everyone’s privacy is entirely a corporate burden. This is unfair to people and companies alike, as well as insane—because it can’t work. (Worse, nearly all B2B “compliance” solutions only solve the felt need by companies to obey the letter of a law while ignoring its spirit. But if people have their own ways to signal their privacy requirements and expectations (as they do with clothing and shelter in the natural world), life gets a lot easier for everybody, because there’s something there to respect. We don’t have that yet online, but it shouldn’t be hard. For more on this, see Privacy is Personal and our own Privacy Manifesto.

- Real relationships: ones in which both parties actually care about and help each other, and good market intelligence flows both ways. Marketing by itself can’t do it. All you get is the sound of one hand slapping. (Or, more typically, pleasuring itself with mountains of data and fanciful maths first described in Darrell Huff’s How to Lie With Statistics, written in 1954). Sales departments can’t do it either, because their job is done once the relationship is established. CRM can’t do it without a VRM hand to shake on the customer’s side. From What Makes a Good Customer: “Consider the fact that a customer’s experience with a product or service is far more rich, persistent and informative than is the company’s experience selling those things, or learning about their use only through customer service calls (or even through pre-installed surveillance systems such as those which for years now have been coming in new cars). The curb weight of customer intelligence (knowledge, know-how, experience) with a company’s products and services far outweighs whatever the company can know or guess at. So, what if that intelligence were to be made available by the customer, independently, and in standard ways that work at scale across many or all of the companies the customer deals with?”

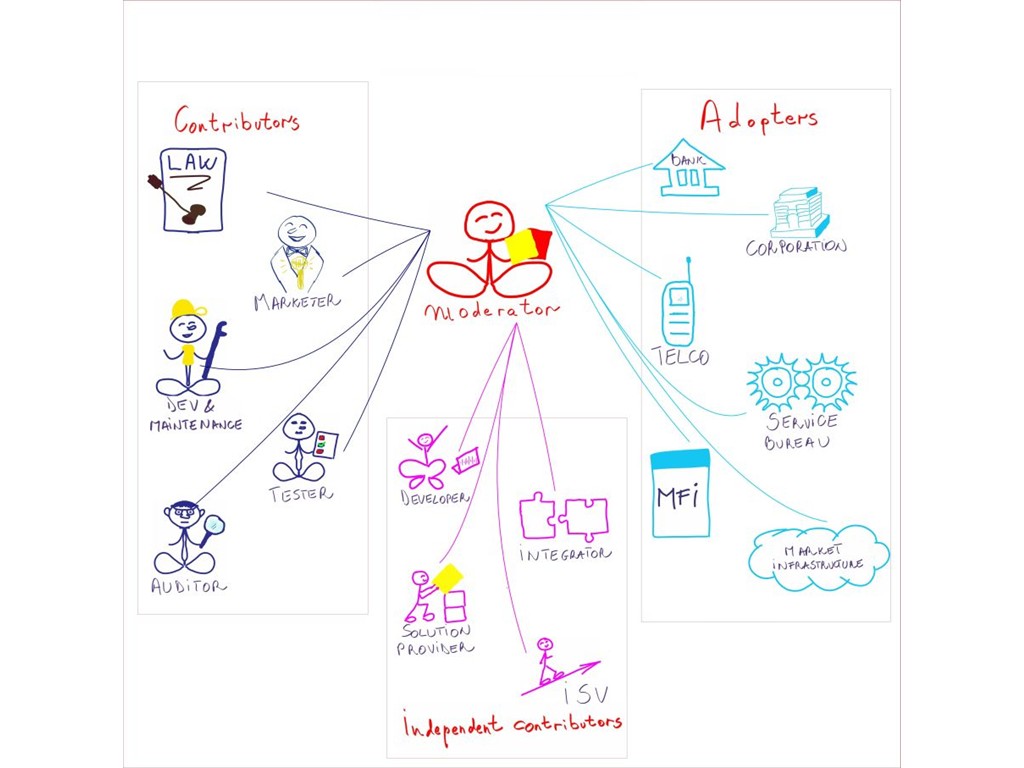

- Any-to-any/many-to-many business: a market environment where anybody can easily do business with anybody else, mostly free of centralizers or controlling intermediaries (with due respect for inevitable tendencies toward federation). There is some movement in this direction around what’s being called Web3.

- Life management platforms. KuppingerCole has been writing and thinking about these since not long after they gave ProjectVRM an award for its work, way back in 2007. These have gone by many labels: personal data clouds, vaults, dashboards, cockpits, lockers, and other ways of characterizing personal control of one’s life where it meets and interacts with the digital world. The personal data that matters in these is the kind that matters in one’s life: health (e.g. HIEofOne), finances, property, subscriptions, contacts, calendar, creative works, and so on, including personal archives for all of it. Social data out in the world also matters, but is not the place to start, because that data is less important than the kinds of personal data listed above—most of which has no business being sold or given away for goodies from marketers. (See We can do better than selling our data.)

All of these, however, are ocean-boiling ideas. In other words, not easy, especially without what the military calls “robust funding.” So our strategies are best aimed toward what are called “blue” rather than “red” (blood filled) oceans. One of those is the Byway (or “buyway”) project by Customer Commons, in Bloomington, Indiana. An excerpt:

There are three parts to the Byway project as it now stands (in July 2022): an online community (Small Town/mastodon), a matcher tool (Intently), and a local e-commerce “buyway.” (For more on that one, download the slide deck presented by Doc and Joyce at The Mill in November 2021. Or download this earlier and shorter one.)

We also see the Byway as complementary to, rather than competitive with, developments with similar and overlapping ambitions, such as SSI, DIDcomm, picos, JLINC, Digital Homesteading / Dazzle and many others.

Joyce and I, both founders and board members of Customer Commons, are heading up to DWeb Camp in a few minutes, and plan to make progress there on Byway development. I’ll report here on progress.

[Later…] DWeb Camp was a great success for us. We are now in planning conversations with developers and others. Stay tuned for more on that.

This is good. Real good. Having Aspen and Knight endorse personal sovereignty as a necessity for solving the crises of democracy and trust also means they endorse what we’ve been pushing forward here for more than a dozen years.

This is good. Real good. Having Aspen and Knight endorse personal sovereignty as a necessity for solving the crises of democracy and trust also means they endorse what we’ve been pushing forward here for more than a dozen years.

Scale for customers means being able to issue signals to whole markets in one move.

Scale for customers means being able to issue signals to whole markets in one move.